Marked Absent: The Impact of Back-to-School Anxiety

Written by: Nick Redgrove

Reviewed by: Liam Taft

Last updated

Contents

- 1. About the data

- 2. The key findings

- 3. When back-to-school anxiety is most prevalent for UK students

- 4. The academic impact of back-to-school anxiety

- 5. The impact of back-to-school anxiety on student wellbeing

- 6. Are schools doing enough to handle the issue of back-to-school anxiety?

- 7. Communication between schools and pupils experiencing back-to-school anxiety

- 8. Conclusions

- 9. Methodology breakdown

In the academic year 2018-19, the last before the Covid-19 pandemic, just over 60,000 pupils in England were classed as “severely absent”. By 2023-24, this number had grown to more than 170,000 (opens in a new tab). “Severe absence” means that these students — 2.3% of all pupils — missed more than 50% of all possible lessons.

In the same year, the number of students missing more than 10% of all possible lessons, and so classed as “persistently absent”, stood at 1.49 million, or approximately one in five students nationwide.

While the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on children’s mental health is complex (opens in a new tab), mental health referrals to the NHS for young people rose 50% (opens in a new tab) over the same time period. Indeed, the NHS estimates that one in five young people in the UK have a probable mental health condition (opens in a new tab), a much higher proportion than in the adult population.

Over 270,000 children are still waiting for support, while almost 40% (372,800) had their referral closed before accessing support (opens in a new tab). According to the Children’s Commissioner, Dame Rachel de Souza, all of this constitutes “a crisis in children’s mental health” (opens in a new tab).

It is in this context that “emotionally based school avoidance” (EBSA) is on the rise: figures suggest that 28% of 12- to 18-year-olds avoid going to school because doing so would make them anxious (opens in a new tab).

Anxiety is the most common reason cited in the nearly 1 million mental health referrals to the NHS by children and young people; 500 children aged 17 and below are referred to NHS mental health services for anxiety every day (opens in a new tab). Recent research has shown that EBSA accounts for a “significant component” of the rise in school absences since 2020. More worryingly, the same report suggested that EBSA “adversely affects children’s educational attainment, health, social functioning and life prospects” (opens in a new tab).

At Save My Exams, we have conducted our own research, in collaboration with Tutorful (opens in a new tab), on what we are terming “back-to-school anxiety”, a major factor in EBSA. Our results show not only that this type of anxiety is widespread, but that it has significant negative consequences on student attendance, attainment, motivation and wellbeing.

We have also investigated the underlying causes of this anxiety (we found that the source of this anxiety is principally academic pressure and social challenges) as well as how it negatively affects their wellbeing outside school.

While the government has pledged additional mental health support for schools and pupils — including a promise to have mental health professionals available to all schools (opens in a new tab) – and have prioritised improving attendance to close the attainment gap (opens in a new tab), our survey has revealed the lack of support students feel they have in terms of back-to-school anxiety: only 6% of UK students feel comfortable talking to a school counsellor or school-based mental health professional about these concerns.

As a result of our findings, we call on the government to implement systemic changes to ensure that schools and pupils are given the support, resources and training they need to challenge the increasing levels of back-to-school anxiety.

About the data

For this report, Save My Exams and Tutorful surveyed over 500 UK secondary school students who are dealing with symptoms of school anxiety. We also submitted a freedom of information request for Department for Education data regarding pupil absence rates over each term.

The key findings

Key findings | |

Timing and duration of anxiety |

|

Academic impact of back-to-school anxiety |

|

Effects on wellbeing |

|

Support and understanding |

|

When back-to-school anxiety is most prevalent for UK students

Key findings |

|

Our survey found that the majority of secondary school students report back-to-school anxiety: over half of all respondents to our survey reported feeling anxious returning to school after a school holiday. Our survey showed that the longer the holiday, the more likely students are to report back-to-school anxiety.

However, for many, this anxiety is not just experienced after school breaks, but something that is felt every day: 20% of students reported feeling back-to-school anxiety before every school day and that they feel this anxiety indefinitely.

Research has suggested that “emotionally based school avoidance” (EBSA) commonly emerges during “educational transitions” (opens in a new tab). These “high-risk periods” have commonly been understood as the transitions students make between, for example, ending primary school and entering a secondary school setting. Our research suggests that we should also take seriously these other, smaller, transitions: between school holidays and term times, or even the transition between home and school.

The academic impact of back-to-school anxiety

Key findings |

|

Our research is clear: back-to-school anxiety is having a significant impact on students’ attainment. 69% of UK students in our survey feel that back-to-school anxiety has had a negative impact on their academic performance.

The scientific consensus on this is robust: persistent absence severely impacts pupils’ attainment (opens in a new tab). In fact, only a small drop-off in attendance can have big consequences to outcomes. The Department for Education has found that at primary school, “children who attend school nearly every day in Year 6 (95-100% attendance) are 30% more likely to reach the expected standard in reading, writing and maths” compared to similar pupils who attend 90–95% of the time.

For secondary-school-aged students — the focus of our study — the figures are even more pronounced: the DfE also calculated that missing just 10 extra days a year reduces the likelihood of achieving a Grade 5 in English Language and Maths at GCSE by around 50%.

Perhaps linked to this is the fact that our research found that 59% of UK students in our survey believed that back-to-school anxiety negatively affected their engagement and motivation at school, and 32% of respondents claimed it affected their ability to concentrate in class.

Furthermore, one in six students reported back-to-school anxiety had led to a decline in their behaviour.

Studies have shown that although students who are persistently absent are more likely to be bullied, they are also more likely to be excluded and engage in risky behaviours (opens in a new tab). Other research suggests that persistent school absence impacts cognitive function, resulting in lower working memory and cognitive flexibility (opens in a new tab).

There is a well-established link between back-to-school anxiety and absence, but what is clear from our research is that the effects of this anxiety on student motivation, engagement, concentration and behaviour are having a severely detrimental impact on student outcomes.

The impact of back-to-school anxiety on student wellbeing

Key findings |

|

Our research highlighted the main causes of back-to-school anxiety: the four main reasons cited were academic pressure, social challenges, schools’ behavioural expectations and changes to routine.

39% of UK students stated that academic pressure — stress about schoolwork, tests, and exams — was a source of back-to-school anxiety. Other major factors included:

19% — worries about socialising (making friends, fitting in, concerns about abuse or bullying)

18% — the pressure to behave well or meet others’ expectations

18% — fear of the unknown: anxiety about new teachers, classes, or routines

Students are feeling a range of sometimes compounding pressures that are all contributing to their back-to-school anxiety. However, it is instructive that by far the most cited reason for this anxiety is academic pressure: the UK tests its children more than most countries in the world (opens in a new tab), and 94% of UK secondary school teachers believe that students were driven towards stress-related conditions during exam periods (opens in a new tab).

Our research also found that back-to-school anxiety displays in a variety of ways, including manifesting in physical symptoms: 33% of UK students stated that back-to-school anxiety led to feeling overwhelmed, nervous or panicked, and 21% of respondents reported insomnia, headaches and vomiting due to their anxiety.

Moreover, back-to-school anxiety is not just affecting students’ wellbeing at school; it is negatively impacting their wellbeing in social settings. A third of UK students reported not being able to switch off and relax during holidays, and many of our respondents also stated that back-to-school anxiety affected relationships with friends.

The fact that back-to-school anxiety is not just affecting the wellbeing of students while in school, but also outside of school, and even during more unstructured holidays that are vital for young people’s development (opens in a new tab), points to the pervasive nature and profound impact of this type of anxiety.

Are schools doing enough to handle the issue of back-to-school anxiety?

Key findings |

|

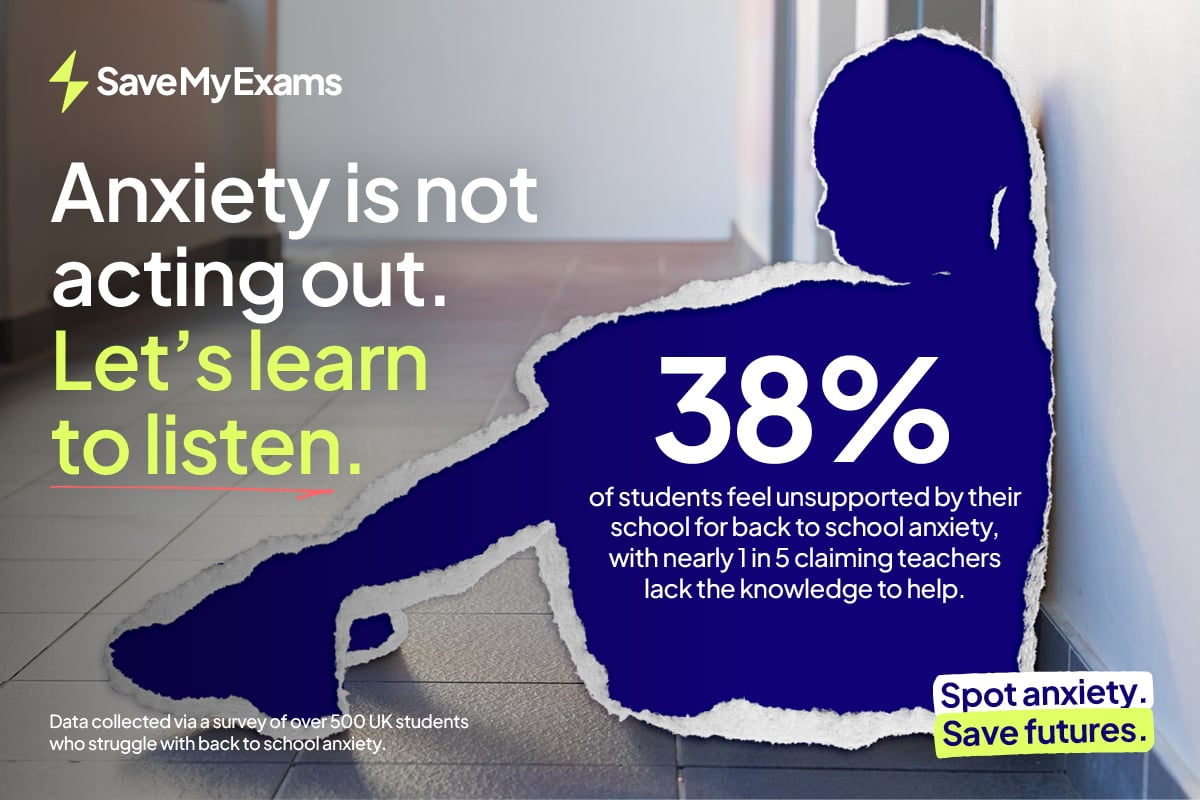

Our research suggested that pupils do not believe that schools are equipped to deal with back-to-school anxiety: 38% of UK students don’t feel supported by their school on issues related to back-to-school anxiety, while just 9% of students stated that they would feel comfortable talking to a member of school staff about it. Perhaps most strikingly, only 6% of UK students stated that they would feel comfortable speaking to a school counsellor or mental health professional about their anxieties.

This points to a major disconnect between students and schools on this issue: a fifth of students we surveyed didn’t believe their teachers were knowledgeable enough to deal adequately with their anxiety. More students would rather not talk about back-to-school anxiety with anyone than do so with a school teacher or counsellor.

Whatever level of mental health provision exists in schools — and even with the Labour government’s pledge of a mental health professional for every school (opens in a new tab) — it is clear that pupils do not currently believe that this provision is suitable. Perception matters here: more needs to be done culturally to encourage and enable students to access support that does exist.

Communication between schools and pupils experiencing back-to-school anxiety

Key findings |

|

Many students in our survey reported not feeling adequately supported by schools in terms of their back-to-school anxiety, but they also pointed to some solutions.

26% of UK students believed that increased flexibility in terms of deadlines and expectations would help ease their back-to-school anxiety, while nearly the same number suggested more understanding and empathy from school professionals would help. Nearly as many respondents claimed that clearer communication about expectations would help them feel less anxious about returning to school.

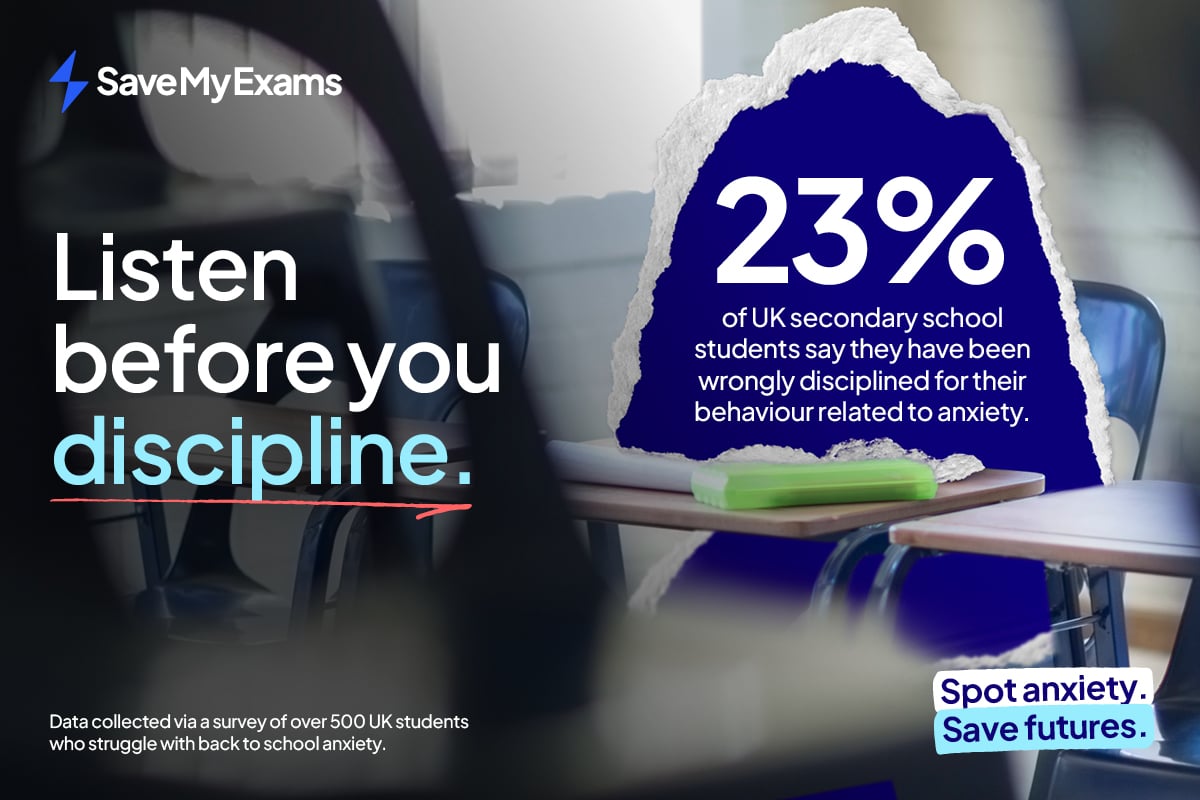

Again, this points to students’ overarching anxieties around both academic and behavioural expectations, and a sense that they feel school professionals are ill-equipped to deal with these kinds of worries. 23% of UK students believe they have been punished for their behaviour related to anxiety.

A recent study by Mind found that 45% of young people aged 13–25 strongly agreed that “school made my mental health worse” (opens in a new tab) and in the same study, 25% of school staff surveyed “said that they were aware of a student being excluded from school because of their mental health”.

Conclusions

Back-to-school anxiety is a significant problem for schools, pupils and their parents. This type of anxiety very often leads to prolonged “emotionally based school avoidance” (EBSA), which in turn has severe consequences for student attainment, motivation and wellbeing.

However, the longer-term consequences of persistent absence are even more stark: according to the DfE, “persistently absent pupils in secondary school could earn £10,000 less at age 28 compared to pupils with near-perfect attendance” (opens in a new tab). Even a small number of absences are statistically significant. According to the same report, “for each additional day of absence between Years 7 to 11, the typical pupil could miss out on an average of £750 in future lifetime earnings”.

Furthermore, the link between school absence and young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) is well established: persistent absence at school (to the age of 16) is associated with a 6.3 times greater risk of being persistently NEET at the age of 18. (opens in a new tab)

Much like the number of severe absences in schools, and the rising number of referrals for children and young people’s mental health services, the number of young people NEET in the UK is also significantly up since 2019. It is also estimated that one in six of young people aged 16–24 who are NEET have a mental health condition (opens in a new tab).

School absence affects disadvantaged students more acutely than the average: according to the DfE’s data, students on Free School Meals, students from single-parent households and students with special educational needs are more likely to be both persistently absent and have mental health issues (opens in a new tab). Tackling the twin problems of mental health and persistent student absence will not only improve the economic prospects of more young people, it will help in closing the attainment gap, allowing more young people to realise their potential.

So what can be done?

The government has pledged to tackle persistent absence in schools, and we welcome, in its announcement of a rollout of mental health support to an additional 900,000 pupils a year (opens in a new tab), that it drew a link between young people’s mental health, wellbeing, attendance and behaviour. It has also announced the introduction of RISE Attendance and Behaviour Hubs, which will support schools, in part, in terms of maintaining good attendance levels.

However, the RISE scheme will only be accessible to 90 schools and the £1.5 million investment for the scheme in 2025 will provide only limited support to students nationwide. As Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said: “[until] there is sufficient capacity in the system for all children to get any additional support they require to be able to attend school on a regular basis … it is difficult to see how attendance rates are going to change at the scale required." (opens in a new tab)

We also call on the Secretary of State for Education, Bridget Phillipson, to refrain from apportioning blame to schools and parents for the issue. Earlier this year, she claimed that some schools are “not making enough progress” (opens in a new tab) on absences, and a DfE statement stated that school absence was also the responsibility of “parents and children”. However, the pressure on school budgets, as well as the joint crises of staff retention (opens in a new tab) and teacher wellbeing, mean that expecting schools to be able to solve this issue without systemic reform and significant resources is simply not feasible.

Our own report detailed the historic lows in terms of teacher wellbeing, but the impact of the pandemic on parents’ mental health (opens in a new tab) should also not be overlooked. Indeed, the significant challenges of having to deal with their children’s own back-to-school anxiety should be acknowledged, too (opens in a new tab).

We are therefore calling on the government to continue to invest in mental health services for schools (their current commitment to providing a mental health professional to all schools by 2030 is insufficient to stem the prevalence of anxiety in school-aged children) and to significantly widen access to RISE centres so that all students in the UK have access to these vital services. They would also do well to work collaboratively with school leaders and parents to provide the support and guidance they need to solve this crisis.

We also believe that further research into the links between persistent absence and children’s emotional wellbeing (such as a recently commissioned report by the Nuffield Foundation (opens in a new tab)), will help better understand what is clearly a complex and significant problem to solve.

Schools can also help by adopting more conciliatory absence procedures. Research has shown that punitive practices such as fines for parents (and punishment for pupils) may even have some negative effects on overall attendance (opens in a new tab). The same report found that parental engagement and regular communication with parents and carers was more effective in reducing absence.

Similarly, as Mind have campaigned for, schools should stop treating mental illness as bad behaviour (opens in a new tab). Lastly, there is some emerging research that suggests that access to enrichment programmes can have a positive effect on student absence (opens in a new tab), as a study by the Centre for Young Lives has shown. As the CEO of the Centre of Young Lives Baroness Anne Longfield says, the current approach is not working, and “we need to be more creative about how to encourage the many children missing school to attend”.

Our report paints a chastening picture of UK students’ mental wellbeing, but we believe that a systematic and collaborative approach, small changes to school culture and improved communication between teachers, parents and pupils can enable our young people to be happy to return to school and thrive once they are there.

Methodology breakdown

Survey

Save My Exams and Tutorful surveyed over 500 UK secondary school-aged students regarding their experiences of school-based anxiety.

Themes of the survey included:

Timing and duration of anxiety – when anxiety peaks (after holidays, weekends, daily) and how long it lasts.

Academic impact of back-to-school anxiety

Effects on student wellbeing and attendance

The level of support and understanding shown by UK schools

The changes students wish to see shown by teachers and institutions

Freedom of Information request to the Department for Education

Save My Exams submitted a freedom of information request to the Department for Education, specifically requesting data on which school term saw the biggest increase in absences between the academic years 2016–17 and 2023–24.

References

Record 170,000 children in England missed at least half of classes in 2024 | School attendance and absence | The Guardian (opens in a new tab)

Understanding the crisis in young people’s mental health (opens in a new tab)

Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2023 - wave 4 follow up to the 2017 survey (opens in a new tab)

Press Notice: Over a quarter of a million children still waiting for mental health support, Children’s Commissioner warns (opens in a new tab)

Children's mental health services 2022-23 | Children's Commissioner for England (opens in a new tab)

Nearly a third of UK secondary pupils avoid school due to anxiety, survey finds (opens in a new tab)

UK childhood mental health crisis to cost £1.1tn in lost pay, study finds (opens in a new tab)

Kathryn J Lester, Daniel Michelson - Perfect storm: emotionally based school avoidance in the post-COVID-19 pandemic context: BMJ Mental Health 2024;27:e300944. (opens in a new tab)

Where are we on Labour’s mental health promises? (opens in a new tab)

Why school attendance matters, and what we’re doing to improve it – The Education Hub (opens in a new tab)

The long-term consequences of early school absences for educational attainment and labour market outcomes (opens in a new tab)

A profile of pupil absence in England (opens in a new tab)

English children 'are most tested in the world' (opens in a new tab)

The impact of exam season on student wellbeing - iSAMS (opens in a new tab)

How Overscheduling Prevents Skill Development | Psychology Today United Kingdom (opens in a new tab)

Not making the grade: | Mind (opens in a new tab)

School absence and not in education, employment or training and Young People (opens in a new tab)

Almost million more pupils get access to mental health support - (opens in a new tab)GOV.UK (opens in a new tab)

The challenges of teacher recruitment and retention in England – Ofsted: education (opens in a new tab)

Classrooms in Crisis: The Impact of Abuse Against Teachers

Working parents, financial insecurity, and childcare: mental health in the time of COVID-19 in the UK (opens in a new tab)

Pupil wellbeing and increased persistent absenteeism: An investigation - Nuffield Foundation (opens in a new tab)

Attendance Interventions: Rapid Assessment (opens in a new tab)

Improving mental health support for young people | Mind (opens in a new tab)

New research reveals positive link between enrichment and tackling the school attendance crisis | Centre for Young Lives | Press Release (opens in a new tab)

Was this article helpful?

Sign up for articles sent directly to your inbox

Receive news, articles and guides directly from our team of experts.

Share this article

written revision resources that improve your

written revision resources that improve your