The Atmosphere as a Global System (Edexcel GCSE Geography A): Revision Note

Exam code: 1GA0

The Features of Global Atmospheric Circulation

The atmosphere is constantly moving solar heat energy FROM the equator TO the poles to reach a balance in temperature

Different areas of the Earth get different amounts of energy from the sun, known as insolation

The Earth is a sphere with a permanent tilt and a slight bulge at its equator

Therefore, the equator gains solar energy but the poles have a deficit of solar energy

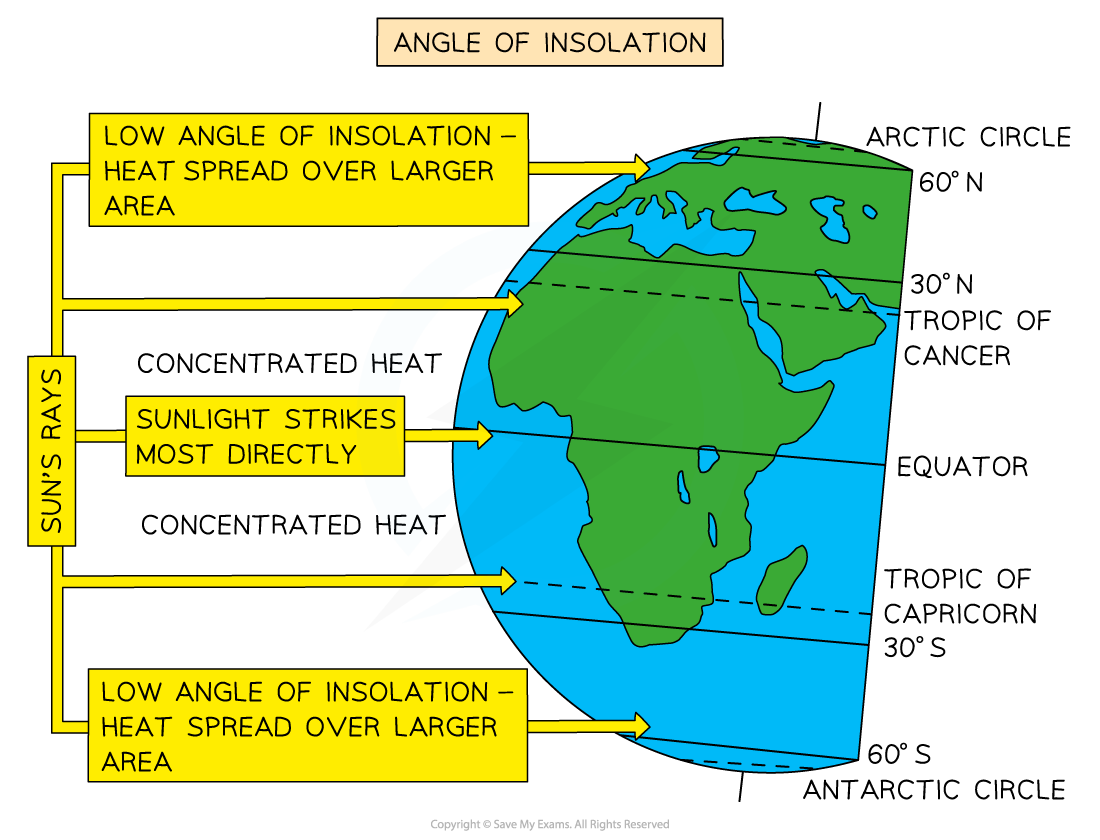

Angle of insolation

Diagram showing how solar radiation is spread over a wider area at the poles than the equator

Wind formation

To circulate the warm air around the Earth, specific wind and pressure patterns exist

Air always moves from high pressure to lower pressure

This movement of air generates wind

Winds are large-scale movements of air due to differences in air pressure

Pressure differences happen because the Sun heats the Earth's surface unevenly

The global circulation system begins at the equator because it is the hottest part of the Earth

Air rises at the equator, leading to low pressure and rainfall at the surface

When the air reaches the edge of the atmosphere, it cannot go any further and so it travels north and south

The air in the atmosphere becomes cold and begins to sink back towards the surface, creating high pressure and dry air

The cool air will then 'rush' from the high-pressure zone to the low-pressure zone at the equator to be warmed again by the Sun, at the same time creating wind

The wind pressure cell system shows the distribution of pressure at Earth's surface and upper atmosphere

Air movement within the cell is roughly circular and helps move surplus heat around the Earth

Each cell generates different weather patterns

Examiner Tips and Tricks

What is weather?

Remember that weather is what you get locally on a day-to-day basis, but climate is what you expect a place to be over time (usually 30 years).

You expect the UK to be wet and cold (not always but mostly!), but you would expect the Mediterranean to be warm—that is climate.

Pressure differences

Air moves in the atmosphere either towards the ground (subsidence) or up into the atmosphere (convection)

These movements influence air pressure and rainfall

The sea and land heat up differently

Sea:

Forms high pressure in summer and low pressure in winter

It takes longer to heat and cool

Air is denser and cooler in summer but warmer in winter

Land:

Generally, it forms areas of lower pressure in summer and higher pressure in winter

It heats quickly in summer and the air is lighter and rises

It cools quickly in winter

Table Showing Influence of Air Movement on Weather Conditions

Air Movement | Cause | Weather Conditions |

Subsidence (sinking air) | It occurs in areas with low-intensity solar radiation, such as the poles or at high altitudes where the air is very cold. Air becomes denser and sinks towards the ground. As air sinks, it begins to warm and can therefore hold more moisture, preventing clouds from forming. | Forms high-pressure areas where the air is descending. Brings clear skies or very thin clouds. Creates arid or semi-arid conditions due to very little precipitation. |

Convection (rising air) | It occurs in areas with high levels of solar radiation. The ground heats the air above and rises. As air rises, it cools and condenses into water droplets, which form clouds. | Low-pressure areas are created as air moves upward. Thick, heavy cloud cover with heavy rainfall creates wet tropical regions. |

A broad pattern of latitudinal high- and low-pressure belts are created via the horizontal bands of the Hadley, Ferrel and Polar cells

However, the distribution of land and sea affects the location of these pressure zones, so the pattern is not symmetrical in each hemisphere, despite the mirroring of the cells

Global pressure belts

Pattern of latitudinal high- and low-pressure belts created by the Hadley, Ferrel and Polar cells

Redistribution of Heat

Heat is transferred around the world by two main methods

Circulation cells

Ocean currents

Circulation cells

In both hemispheres, heat energy transfer occurs where 3 atmospheric circulation cells meet

These are the Hadley, Ferrel, and Polar cells and are shown via the tri-cellular model

The tri-cellular model

Each hemisphere has three cells (the Hadley cell, Ferrel cell and Polar cell)

These circulate air from the Earth's surface through the atmosphere and back again

The Hadley cell is the largest and extends from the equator to between 30° and 40° north and south

Trade winds blow from the tropical regions to the equator and travel in an easterly direction

Near the equator, the trade winds meet, and the hot air rises and forms thunderstorms (tropical rainstorms)

From the top of these storms, air flows towards higher latitudes, where it becomes cooler and sinks over subtropical regions

This brings dry, cloudless air, which is warmed by the Sun as it descends

The climate is warm and dry (hot deserts are usually found here)

Ferrel cell is in the middle and occurs from the edge of the Hadley cell to between 60° and 70° north and south of the equator

This is the most complicated cell, as it moves in the opposite direction from the Hadley and Polar cells

Air in this cell joins the sinking air of the Hadley cell and travels at low heights to mid-latitudes, where it rises along the border with the cold air of the Polar cell

This occurs in the mid-latitudes and is the reason for lots of unsettled weather (particularly in the UK)

The polar cell is the smallest and weakest of the atmospheric cells

It extends from the edge of the Ferrel cell to the poles at 90° north and south

The air in these cells is cold and sinks, creating high pressure over the highest latitudes

The cold air flows out towards the lower latitudes at the surface, where it is slightly warmed and rises to return at altitude to the poles

Coriolis effect

Each cell has prevailing winds associated with it

These winds are influenced by the Coriolis effect

The Coriolis effect is the appearance that global winds and ocean currents curve as they move

The curve is due to the Earth's rotation on its axis, and this forces the winds to actually blow diagonally

The Coriolis effect influences wind direction around the world in this way:

In the northern hemisphere it curves winds to the right

In the southern hemisphere it curves them left

The exception is when there is a low-pressure system:

In these systems, the winds flow in reverse (anticlockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern hemisphere)

Global wind belts – surface winds

The combination of pressure cells, the Coriolis effect, and the three cells produce wind belts in each hemisphere

The trade winds: Blow from the subtropical high-pressure belts (30° N and S) towards the Equator's low-pressure zones and are deflected by the Coriolis force

The westerlies: Blow from the sub-tropical high-pressure belts to the mid-latitude low areas, but again, are deflected by the Coriolis force

The easterlies: Polar easterlies meet the westerlies at 60° S

Global atmospheric circulation affects the Earth's climate

It causes some areas to have certain types of weather more frequently than other areas:

The UK has a lot of low-pressure weather systems that are blown in from the Atlantic Ocean on south-westerly winds, bringing wet and windy weather

Ocean conveyor belt

Ocean currents move heat energy around the globe

Currents (warm or cold) act like 'rivers' of water in the sea

Cold currents move towards the equator and warm currents move towards the poles

Each ocean has its own pattern of current

E.g. the warm Atlantic Ocean waters of the low latitudes are moved to high latitudes via the North Atlantic Drift

The direction of all ocean currents occur because of the Coriolis effect and prevailing surface winds

Circulation occurs through convection currents

These are driven by cold water freezing into ice at the poles

The polar cold waters are denser, saltier seawater which sinks to the ocean floor

Water then flows in behind it at the surface, which forms a current

The deep ocean currents then flow towards Antarctica along the western Atlantic basin, then split off into the Indian and Pacific Oceans, where the water begins to warm up

The warming makes the water less dense so it loops back up to the surface in the South and North Atlantic Ocean

The warmed surface waters continue to flow around the globe and eventually return to the North Atlantic, where the cycle begins again

This movement of water is known as the thermohaline circulation and drives the ocean conveyor belt

Image of the ocean conveyor belt

Worked Example

The atmosphere operates as a global system, transferring heat and energy.

Name one of the global atmospheric circulation cells.

(1)

Answer:

1 mark for correctly identifying either:

Ferrel

Hadley or

Polar

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?