Punishment in the 19th Century (WJEC Eduqas GCSE History): Revision Note

Exam code: C100

Timeline

How did Traditional Punishments Evolve During the 19th Century?- Summary

Punishment in the 19th century still relied on many of the same punishments used before the Norman Conquest, such as stocks, pillories and executions. However, public opinion began to change as people increasingly saw these punishments as inhumane and ineffective. The use of transportation to North America and later Australia aimed to reduce crime while avoiding the death penalty, but this also decreased. Instead, the focus turned to prison reform. New prisons such as Pentonville reflected growing interest in discipline, reflection, and moral reform. Influential reformers, including John Howard, Elizabeth Fry, and Sir George O Paul, helped transform prisons from filthy, overcrowded places into institutions aimed at rehabilitating offenders, marking a significant change in Britain’s approach to punishment.

The Use of Stocks, Pillory & Executions

The use of stocks, pillories and executions was not new to the 19th century

Some had been used since before the Norman Conquest

They continued to be used until the 19th century

The use of stocks and the pillory was abolished in 1837

Stocks

The Act of 1351 stated that stocks had to be set up in villages

As a punishment for runaway servants and labourers

They were also used as punishment for minor crimes

The Act of 1406 stated that stocks were to be

Set up in every town

Used as a punishment for

Drunkeness

Profaners

Gamblers

Vagrants

Those who failed to pay their fines

Pillory

Pillories were used in Britain before the Norman Conquest

The pillory was used for those people who

Sold goods underweight

Cheat at cards

Swore a lot

When in the pillory, some crowds would throw things at the criminals, including

Stones

Rotten food

Some people were even attacked and killed in the pillory

Especially if they were convicted of a serious crime

Such as sexual assaults

Execution

Since the 16th century, execution has been used as a punishment for serious crimes, including

Murder

Treason

Arson

Counterfeting

During the Tudor and Stuart eras, many minor crimes were punishable by execution

The Waltham Black Act of 1723 became known as the ‘Bloody Code’

This resulted in a large number of capital offences over a period of time

The death penalty was the punishment for 50 different crimes in the Tudor and Stuart periods

For example, thieves were executed if they stole goods worth over one shilling (5p)

This number increased to over 200, and included

Murder

Pickpocketing

Horse theft

Executions were always carried out in public

Unless the criminal was a member of the nobility

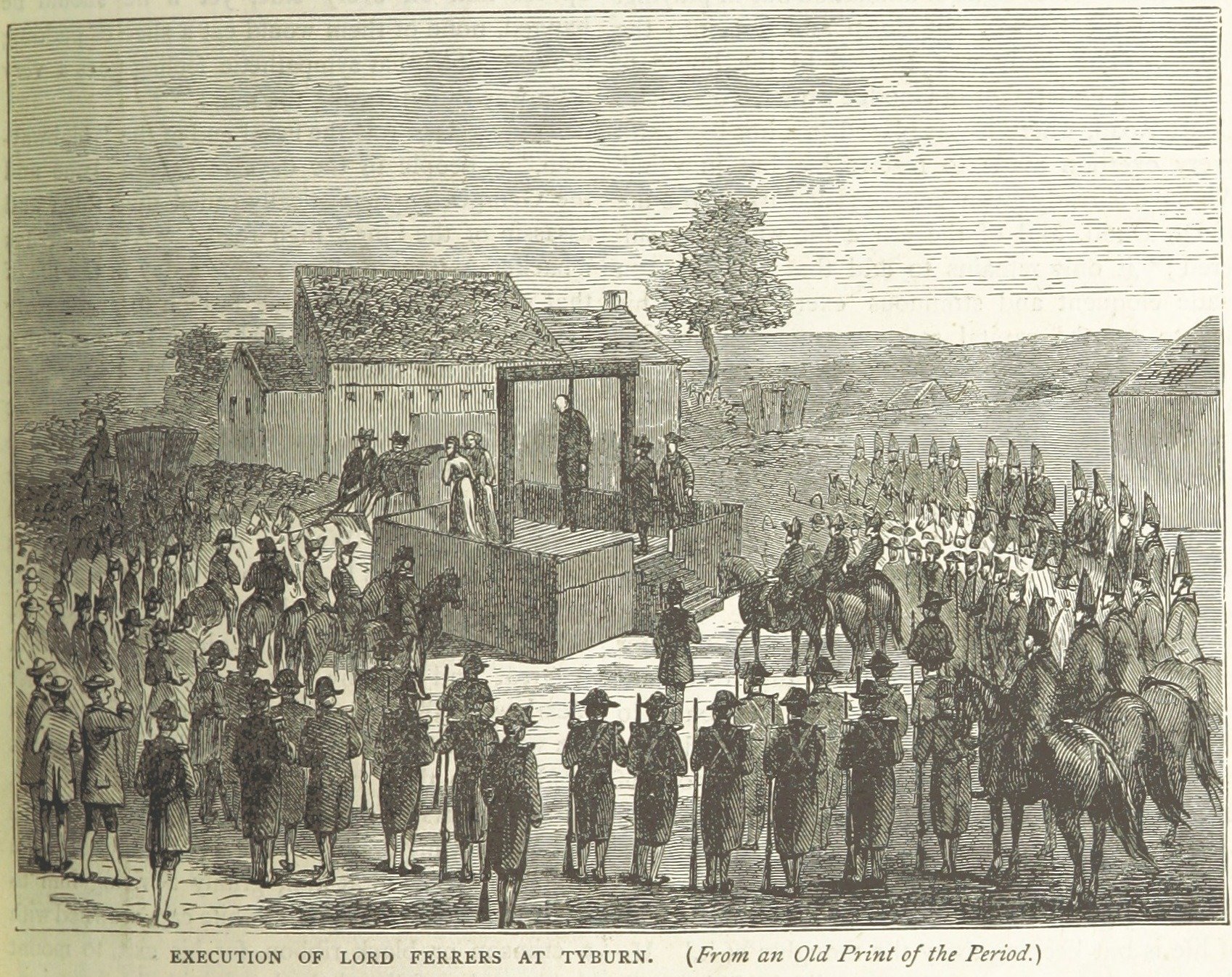

One of the most famous locations in London for executions was called Tyburn

Near the location where the Marble Arch is today

The gallows structure was nicknamed the Tyburn Tree

Businesses would close so people could attend the executions

In 1724, it is believed that over 200,000 people watched Jack Sheppard (a famous thief) be executed for his crimes

Between 1703 and 1792, approximately 1,232 people were hanged at Tyburn

Of these, 92 were women

90% were men under 21 years old

The Use of Transportation

Transportation started to be used as a punishment during James I’s reign

However, the 1717 Transportation Act formally set up the transportation system

Some criminals could choose to be transported or another punishment such as branding, whipping or hanging

Those who were transported were sent on ships to the new colonies of North America, as well as the Caribbean

Here, they did manual work by helping to build settlements

Working conditions were very harsh

Transportation became a popular punishment in England and Wales because

Execution was seen as too harsh for some crimes

Such as hanging

Prisons were overcrowded

It was believed that removing the criminals would decrease crime

Transportation acted as a deterrent

People were put off by crime due to the harsh conditions on ships and in the colonies

It was cost-effective

Imprisonment was too expensive

It was believed that criminals would

Learn new skills

Have an opportunity for a new life after their sentence is completed

It would help to colonise the colonies

As they would eventually be populated with British subjects

Sentences were either seven or 14 years

Once their sentence was over, many could not afford to return to England and Wales

Between 50,000 and 80,000 people were transported to North America, including

Men

Women

Children

Transported vagabond children became known as ‘duty boys’

By the late 18th century, transportation was the most frequently used punishment in Britain

After the American War of Independence in 1776, the North American colonies were no longer used for transportation

The government used ships as prisons, known as ‘hulks’

This was a temporary measure until another colony could be used for transportation

Conditions were poor as they were unhygienic, poorly maintained and often witnessed fights and rioting

Between 1776 and 1778, more than a quarter of prisoners on ‘hulks’ died

Eventually, conditions improved after a public inquiry into the conditions

In May 1787, criminals were transported to Australia

Around 160,000 people were transported to Australia

One in six people on the ship were women

Most were thieves (especially reoffenders)

A small number were political protesters

The first penal colony was New South Wales

Conditions were harsh in the new colony, and many died

Convicts in Australia were

Domestic workers

Skilled workers

Farm workers

In labour gangs

If the convicts in Australia showed good behaviour, they would be rewarded with

A ticket of leave

This allowed them to live freely in a district in the colony at the end of their sentence

Certificate of freedom

Introduced in 1810

Given at the end of a sentence

Conditional pardon

Convict was given freedom, but not allowed to return to their home

Absolute pardon

The convict was given freedom

Cleared of charges

Allowed to return home

By the 1840s, transportation began to decline as

A Parliamentary Committee of Enquiry in 1838 reported that

It was not enough of a deterrent

It was too expensive to maintain

Australians resented their country being used as a penal colony

It did not decrease crime in England and Wales

Although the government believed it would decrease crime, it actually increased crime

The Need for Prison Reform

Early modern prisons were mainly used to hold criminals awaiting trial

This changed in the 18th and 19th centuries

Imprisonment was increasingly used as a form of punishment

It became even more common after transportation ended

Prison conditions were very poor

In 1729, a report by a government committee found that prisoners were

At the point of starvation

Dying from a lack of food

Prisons were privately owned by businessmen who wanted to make a profit

Gaolers made a profit by charging for

Food

Bedding

Any other necessities

Many thought that criminals in prison deserved these poor conditions

Others thought that improving prison conditions would increase criminals’ chances of rehabilitation

Three key reformers who shared this view were

John Howard

Sir George O Paul

Elizabeth Fry

Howard, Paul & Fry

John Howard

In his early life, John Howard was imprisoned in France by French pirates, which had a long-lasting effect on him

In 1773, Howard became the High Sheriff of Bedfordshire

He was shocked at the conditions of the jails and decided to visit other prisons in England

In 1775, he visited prisons in Europe, too

In 1776, Howard created a survey of prisons in England, which showed

Most prisoners were debtors

Only a quarter of prisoners had committed serious crimes

Howard published a book in 1777, entitled The State of the Prisons in England and Wales

Based on his findings from the prison survey outlining

The problems

How to address the problems

In 1773, Howard presented his evidence to a Parliamentary Committee

Howard suggested that prisons should be

Hygienic

Roommy

Safe

Howard also argued for

Salaries for gaols

Training for prisoners to help them reform

Better food for prisoners

Regular inspections of prisons

Separation of prisoners so they could not learn about crime from other criminals

Prisoners are to be released immediately when they have served their sentence

Howard’s work led to the 1774 Gaols Act, which contained two pieces of legislation

The Health of the Prisoners Act

This ensured hygienic conditions in prisons, as well as a prison surgeon and infirmaries

The Discharged Prisoners Act

Abolished the fees that prisoners had to pay when they were released

Allowing all prisoners to be released immediately after their sentences were finished

Sir George O Paul

Sir George O Paul was the High Sheriff of Gloucester

He was concerned with prison conditions

In 1784, he published a book entitled Thoughts on the Alarming Progress of Jail Fever

This led to a prison reform in Gloucestershire

In 1785, Paul led the Gloucestershire Prison Act, which stated that all new prisons had to have a

Perimeter wall of 5.4 meters

Allowing staff to observe the prisoners

An isolated area for new prisoners where they would

Receive a bath

Have their clothes disinfected

Be checked by a doctor

Excercise yard

Areas are separated for those

Awating trail

Who committed minor offences

Who committed more serious crimes

Separate areas for different genders

Chapel

Workroom

Darkened cells for punishments

These designs were later copied by other prisons in England and Wales

Elizabeth Fry

Elizabeth Fry was a Quaker and was inspired by the work of Sir George O Paul

In 1813, she visited the women’s section of Newgate Prison

She was concerned about the conditions of the prison

Fry campaigned to improve prison conditions for women

Hoping this would help to reform prisoners

Fry helped to improve the conditions of female prisoners by

Forming the Association for the Improvement of Women Prisoners in 1817, which gave women in prison access to

Education

Religion

Work

Fry’s contributions to the improvement of prisons made way for changes to other prisons, including

The appointment of female warders

The creation of schools for female prisoners and their children

The introduction of work for female prisoners

Including needlework and knitting

New Prisons

The Gaols Act, 1823

Influenced by the work of Elizabeth Fry and John Howard, the Home Secretary Sir Robert Peel passed the 1823 Gaols Act

This act only applied to

The 130 prisons in London

The counties

As well as 17 large towns

The act stated that

New prisons to be established in each county and large town

Prisons were controlled by the local magistrates and paid for by local rates

Prisons were inspected by justices of the peace

Their findings were to be presented to the Quarter Sessions

An annual report would be sent to the Home Office

A strict system of discipline was to be enacted in all prisons

Gaolers received a salary

Prisoners to be classified by

Gender

Age

Crime

Length of prison sentence

The act had little impact on prisons as

It was ignored by many

Only five inspectors were appointed

Inspectors did not have many powers

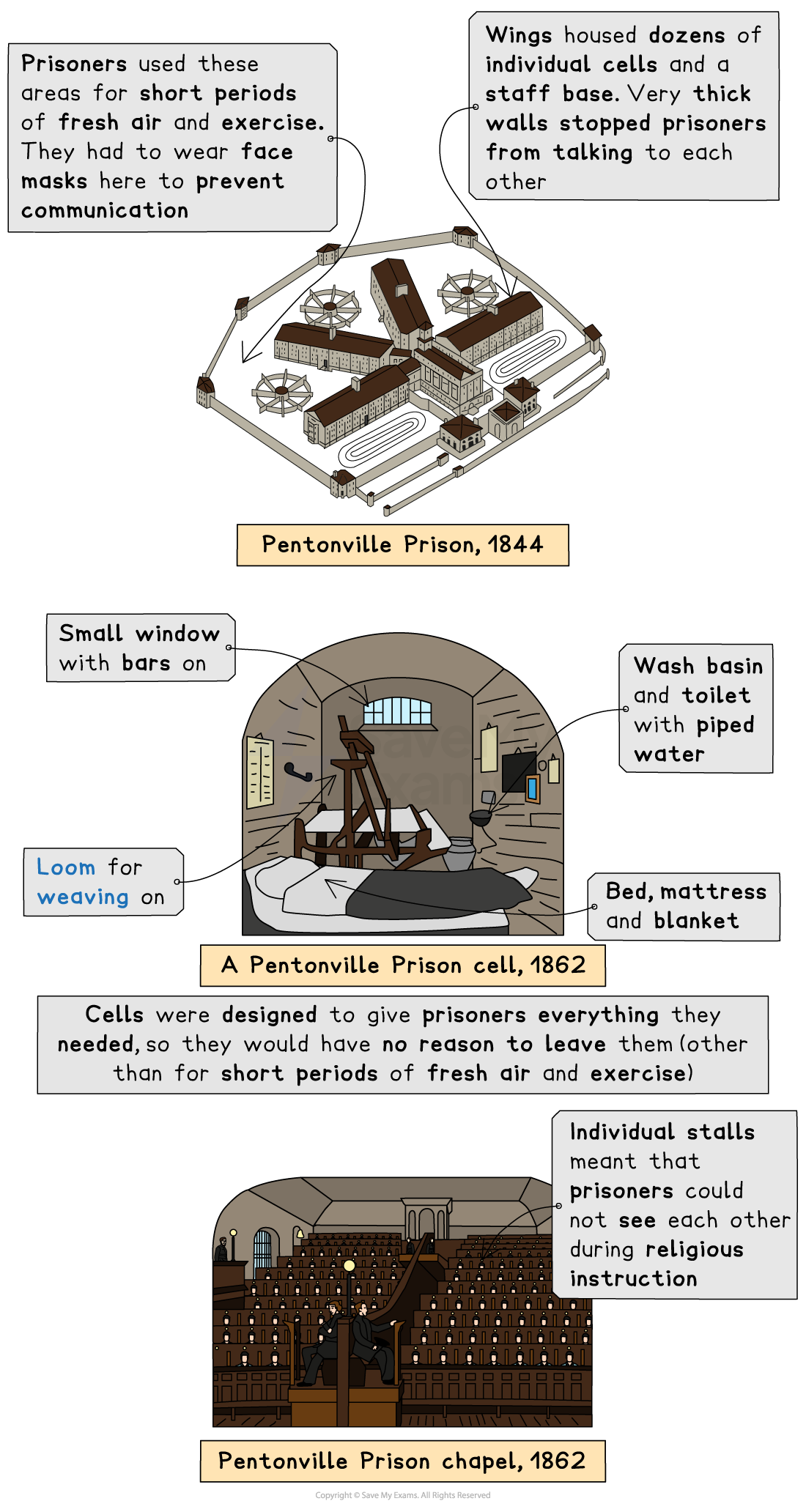

Pentonville Prison

From 1842 to 1877, the government built 90 prisons in Britain

The most famous was Pentonville Prison, London, built in 1842

Pentonville Prison was made to

To house the increasingly large number of criminals

In this period, transportation and execution decreased

This meant that more criminals were in Britain

Pentonville Prison kept such criminals away from society

Act as a model for new ideas

Reformers suggested improvements in the running of prisons and the treatment of prisoners

Pentonville Prison became a place to test out these ideas

The main aim of Pentonville Prison was to reform prisoners

Many also saw it as a place of deterrence and retribution

Examiner Tips and Tricks

In Question 5, don’t just write about prisons; connect them to wider social changes such as urbanisation, industrialisation, and the government’s shift from a laissez-faire approach to greater intervention.

Examiners reward answers that can link the historical context behind prison reform to government involvement and social change for higher-level marks.

Jeremy Bentham

Many individuals argued about how prisoners should be treated

Rev. Sydney Smith argued that life for prisoners should be harsh and unpleasant

To deter criminals

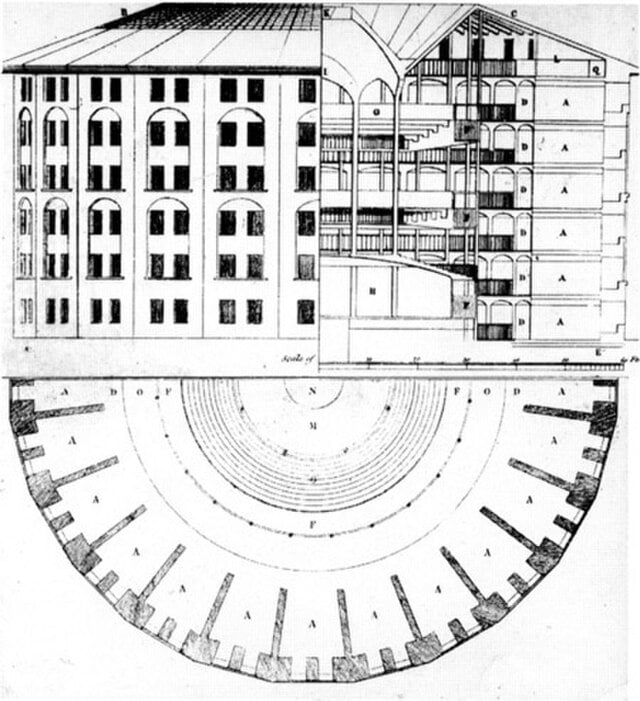

However, Jeremy Bentham believed that prisoners should work

To help with the costs of running a prison

Bentham also believed that prisons with blocks should fan out from the centre

So only a few prison guards would be needed to supervise the whole prison

This design was known as the Panopticon

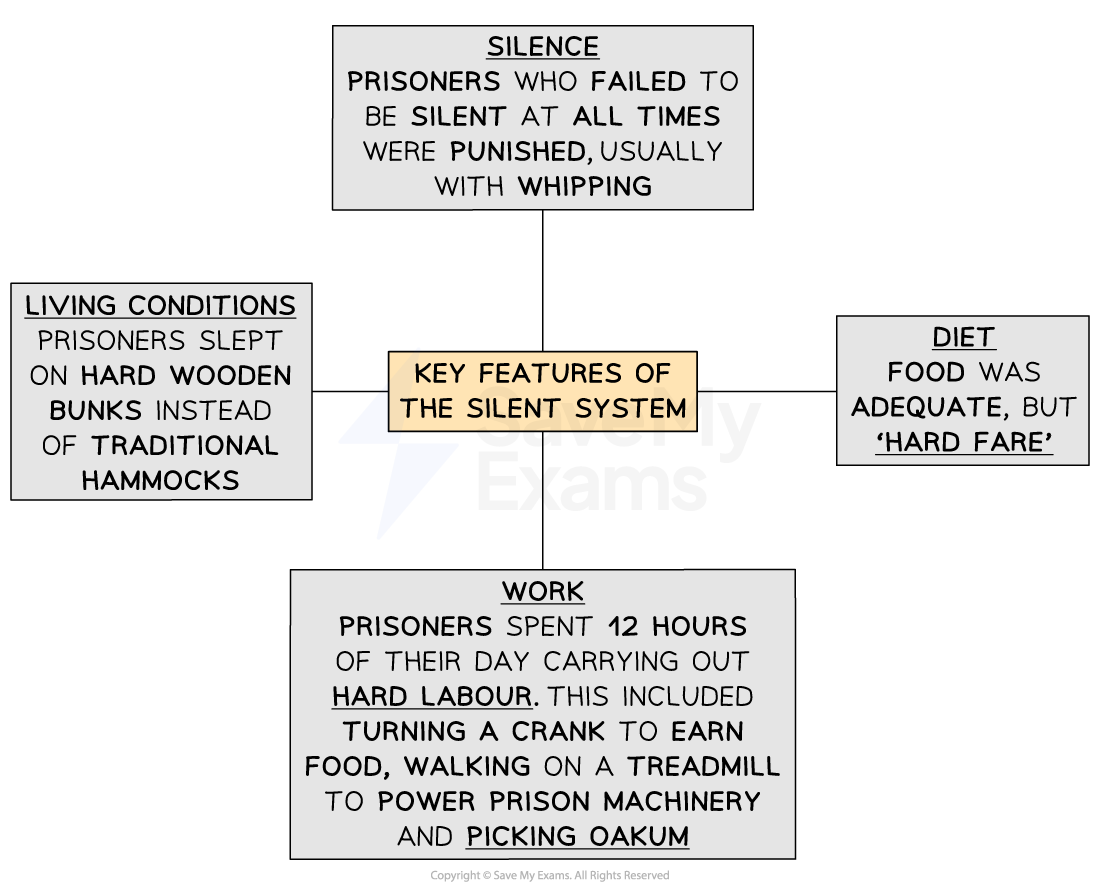

The Silent & Separate Systems

In the late 19th century, prisons often used either the

Silent system

Separate system

Both systems were inspired by prisons in the USA

They were designed to prevent prisoners from talking to each other

The Silent System

The government’s introduction of the silent system marked a change in prisons

They became more focused on deterrence and retribution, rather than rehabilitation

The warders enforced silence so prisoners could not talk to each other

This stopped prisoners from discussing crime or influencing each other

Prisoners were allowed to see each other, but in silence, in

Workrooms

Dining halls

The silent system could work if the prisoners disliked prison and were bored, so prisoners' tasks in the day would involve activities such as

Oakum- picking

Prisoners had to clean a rope covered in tar

Walking on a treadmill, a tread wheel or an everlasting staircase

The crank

A large handle that was required to be turned 1,000 times a day

The Separate System

The separate system focused on reforming prisoners through

Isolation

Work

Religion

Prisoners were

In individual cells

Where they worked and prayed

Visited by clergymen

Prisoners only left their cells for

Religious services

Where they were in individual cubicles

Exercise

Where they would hold a knotted rope

Knots were 4.5 meters apart

If prisoners met, they would wear masks so they would not communicate or see each other

The separate system had many strengths, such as:

Cleaner prisons

Isolation prevented diseases from spreading

The right level of punishment

Many believed that separate prison systems were neither too harsh nor too lenient

No prisoner corruption

Prisoners did not interact with each other, so they could not influence each other

However, the separate system also had many weaknesses, such as:

High levels of mental illness

Continuous isolation increased people's risk of depression, psychosis and suicide

In the first eight years at Pentonville Prison, 26 prisoners had a nervous breakdown,n and three killed themselves

Lack of education

Prisoners were not taught any skills that they could use once released. This limited their chances of rehabilitation

High expenses

Keeping prisoners in individual cells was much more costly than having them mixed together

Examiner Tips and Tricks

Many students become confused about the term ‘separate system’. They often mistakenly explain it in terms of John Howard’s reforms, where criminals were separated according to their gender and class. Remember that the separate system is about keeping criminals isolated (apart from one another).

Government-Controlled Prisons

In the late 19th century, the government became more involved in the control and organisation of prisons

The 1865 Prisons Act focused more on strict punishment, rather than reform, as prisons enforced

Hard labour

Such as the crank, for at least three months

Hard fare

A diet of bread and water for three days

Hard board

Prisoners slept in board beds

By 1877, the Prisons Act brought all prisons under the control of the Home Office

Officially centralising prisons

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?