Hardest International A Level Chemistry Questions & How to Answer Them

Written by: Richard Boole

Reviewed by: Philippa Platt

Published

Contents

Preparing for International A-Level (IAL) Chemistry means facing some genuinely challenging questions. These questions are designed to test the limits of your knowledge and problem-solving ability. These are the questions that separate A* students from the rest, but is the subject's reputation for being difficult really deserved? For a full statistical breakdown, check out our in-depth guide: Is A Level Chemistry Hard?

As a long-standing GCSE and A-Level Chemistry examiner for both Edexcel and OCR, I've marked thousands of exam scripts and seen exactly where students stumble. Combining that firsthand examiner experience with a deep analysis of official examiner reports, this Save My Exams guide breaks down what makes certain IAL questions so hard and shows you how to tackle them with confidence.

Key takeaways

The hardest IAL Chemistry questions test skills, not just topics. They consistently focus on:

Applying knowledge to unfamiliar situations.

Tackling multi-step, unstructured calculations.

Building detailed, synoptic arguments.

Interpreting practical data and evaluating errors.

Using precise scientific language in explanations.

Success comes from a systematic approach:

Breaking down the question

Identifying key information

Showing clear working, which is essential for securing method marks, even if your final answer is wrong.

This guide uses real exam questions and insights from official examiner reports to show you exactly what top-grade answers look like and the common pitfalls to avoid.

Why are some IAL Chemistry questions so difficult?

To understand what makes a question hard, you need to know what examiners are testing. Your final grade is determined by your performance across three Assessment Objectives (AOs). Here's what they mean in practice:

AO1: Knowledge and understanding

This tests what you can remember, such as:

Definitions, e.g. 'State what is meant by...'

Equations

Reaction conditions.

These are typically the more straightforward marks.

AO2: Application

This tests if you can use your knowledge in new situations. This could involve:

Solving a calculation

Applying a principle to an unfamiliar context

Interpreting data

AO3: Analysis and evaluation

This tests your ability to:

Dissect information

Evaluate experimental methods

Identify patterns

Draw conclusions

The hardest questions are deliberately designed to be heavy on AO2 and AO3. They test whether you can think like a chemist, not just remember facts.

So, what do these AO2 and AO3 questions look like in a real exam?

We've analysed years of official examiner reports, and the toughest questions consistently fall into one of these five categories:

1. Precision in language

These are questions that require deep, precise explanations. This means that the common, vague student answers are not enough to score the top marks. Examples include:

Explaining electrode potentials

Buffer action

Trends in bonding

2. Application to unfamiliar contexts

This involves taking a known concept and applying it to a novel scenario that isn't explicitly in the textbook. Examples include:

Mechanisms

Equilibrium principles

3. Multi-step, unstructured calculations

These are problems that require you to combine multiple calculation steps where the path is not immediately obvious. Examples include:

Back titrations

Multi-stage yield calculations

Combining gas laws with stoichiometry

4. Data interpretation & practical skills

This includes:

Reading graphs

Interpreting spectra

Understanding the why behind practical steps (not just the what)

Dealing with percentage uncertainty

5. Synoptic "Levels of Response" questions

These questions require you to pull together information from multiple different areas of the specification into a coherent, written answer. Examples include:

Practical techniques

Structure and bonding

Energetics

Before we dive into the examples, it's crucial to know your exam board. The structure of the papers differs between Edexcel IAL and Cambridge International. This will affect where you're most likely to encounter these challenging questions. For a full breakdown, check out our guide on: How many A Level Chemistry papers there are?

Examples of the hardest International A-Level Chemistry questions

These examples illustrate the five toughest types of questions you'll encounter and show you how to build your answer.

Example 1: Using precise language (The A detail!)*

At the highest level, IAL Chemistry isn't just about knowing the right concept; it's about explaining why it's right with scientific precision. Questions that ask you to "Explain" are designed to test the depth of your conceptual understanding, and vague language will lose you marks.

This question from a Cambridge International paper is a perfect illustration:

State the relative basicities of ethanamide, diethylamine and ethylamine in aqueous solution.

Explain your answer.

[4 marks]

[Source: CIE A-Level Chemistry (9701/41) - June 2023, Q7a (opens in a new tab)]

Why it's tricky:

This question probes a fundamental concept in organic chemistry, but most students only provide a partial explanation.

The June 2023 CIE Examiner Report for this paper notes that while stronger candidates gave good explanations, weaker candidates provided vague or imprecise answers. Key issues included:

Using imprecise terms like "attracts a proton" instead of the correct "accepts a proton."

Failing to explain why an amide is a much weaker base, with the report stating, "The lack of basicity of an amide is due to the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom being delocalised into the C=O group."

What the examiner is looking for:

A detailed, comparative answer that precisely explains the electronic factors affecting the availability of the nitrogen lone pair in all three molecules.

Worked solution:

A top-grade answer requires a logical, three-part structure.

Step 1: State the order of basicity

Start by clearly ranking the compounds from most to least basic:

Diethylamine > Ethylamine > Ethanamide

Step 2: Explain the difference between the amines

Define basicity:

State that the basicity of these nitrogen compounds depends on the availability of the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom to accept a proton (H+).

Explain the inductive effect:

Alkyl groups (like ethyl, C2H5) have a positive inductive effect, meaning they are electron-donating. They push electron density towards the nitrogen atom.

Compare:

Ethylamine has one ethyl group, which increases the electron density on the nitrogen atom, making its lone pair more available than in ammonia.

Diethylamine has two ethyl groups. This results in a stronger combined positive inductive effect, pushing even more electron density onto the nitrogen. This makes its lone pair the most available of the three, and therefore makes diethylamine the strongest base.

Step 3: Explain why the amide is the weakest base

Explain delocalisation:

In ethanamide, the nitrogen atom is bonded to a carbonyl (C=O) group. The lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom is delocalised into the pi-system of the C=O group.

Show the consequence:

This delocalisation means the lone pair is spread across the O-C-N system and is far less available to accept a proton. This makes ethanamide a very weak base, significantly weaker than both amines.

Common pitfalls:

Vague language

Saying an amine "attracts protons" instead of "accepts a proton" or "forms a coordinate bond with a proton."

Stating that alkyl groups "give electrons" without using the precise term positive inductive effect.

Incomplete explanations

Saying diethylamine is a stronger base because it has "more alkyl groups" without explaining that this leads to a greater inductive effect and higher electron density on the nitrogen.

Stating that ethanamide is a weak base but failing to mention the key reason: delocalisation of the lone pair into the carbonyl group.

How to succeed:

Always define the core concept

Start by defining basicity in terms of lone pair availability. This sets the stage for your entire explanation.

Use key scientific terms

Ensure your answer is packed with the precise terms that examiners are looking for:

Lone pair

Positive inductive effect

Electron-donating

Electron density

Delocalisation / delocalised

Pi-system / Carbonyl group

Compare, don't just describe

Use comparative language throughout (e.g., "stronger effect," "more available," "less available") to make the links between the three molecules explicit.

Example 2: Applying rules to unfamiliar contexts

The toughest AO2 questions present you with a scenario you haven't memorised and force you to apply fundamental principles to solve it. This tests true understanding, not just recall.

This Edexcel question on the sequential reduction of vanadium is a classic example of this in action:

Excess zinc powder is added to an acidified solution of the compound NH4VO3. Using the data in the table, explain the sequence of reactions that takes place. In your answer, include a description of what you would see, and the relevant ionic equations with their calculated E°cell values.

Electrode system | Eθ / V |

V2+ (aq) + 2e- ⇌ V (s) | -1.18 |

V3+ (aq) + e- ⇌ V2+ (aq) | -0.26 |

VO2+ (aq) + 2H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ V3+ (aq) + H2O (l) | +0.34 |

VO3- (aq) + 4H+ (aq) + e- ⇌ VO2+ (aq) + 2H2O (l) | +1.00 |

Zn2+ (aq) + 2e- ⇌ Zn (s) | -0.76 |

[7 marks]

[Source: Edexcel International A-Level Chemistry - June 2018, Paper 3, Q5b]

Why it's tricky:

This question is a beast. You can't just recall the colours of vanadium ions. You have to predict, step-by-step, how far the reduction will go by applying electrochemical principles to a system you've likely never encountered in this format.

The Edexcel IAL June 2018 Examiner Report noted that while many candidates could recall the colours, they often:

Confused the order of the colour changes.

Struggled to construct the overall ionic equations.

Failed to use the Eθcell values to justify why each step was happening.

What the examiner is looking for:

A systematic, step-by-step explanation.

They are testing your ability to repeatedly apply the rules of electrochemistry to predict a sequence of feasible reactions and link them to observable changes.

Worked solution:

The key is to be systematic. The reducing agent is zinc (Eθ = -0.76 V). The starting vanadium species is the vanadate(V) ion, VO3- (oxidation State = +5).

Step 1: First reduction (V5+ → V4+)

Identify half-equations:

Oxidation: Zn (s) → Zn2+ (aq) + 2e- (Eθ = +0.76 V)

Reduction: VO3- (aq) + 4H+ (aq) + e- → VO2+ (aq) + 2H2O (l) (Eθ = +1.00 V)

Calculate Eθcell:

Eθcell = Eθred - Eθox = (+1.00) - (-0.76) = +1.76 V.

Conclusion: Since Eθcell is positive, the reaction is feasible. Vanadium(V) is reduced to Vanadium(IV).

Observation: The solution will change from yellow (VO3-) to blue (VO2+).

Step 2: Second reduction (V4+ → V2+)

Identify half-equations:

Oxidation: Zn (s) → Zn2+ (aq) + 2e- (Eθ = +0.76 V)

Reduction: VO2+ (aq) + 2H+ (aq) + e- → V3+ (aq) + H2O (l) (Eθ = +0.34 V)

Calculate Eθcell:

Eθcell = Eθred - Eθox = (+0.34) - (-0.76) = +1.10 V.

Conclusion: Eθcell is positive, so the reaction is feasible. The V4+ formed in step 1 is further reduced.

Observation: The solution will change from blue (VO2+) to green (V3+).

Step 3: Third reduction (V3+ → V2+)

Identify half-equations:

Oxidation: Zn (s) → Zn2+ (aq) + 2e- (Eθ = +0.76 V)

Reduction: V3+ (aq) + e⁻ → V2+ (aq) (Eθ = -0.26 V)

Calculate Eθcell:

Eθcell = Eθred - Eθox = (-0.26) - (-0.76) = +0.50 V.

Conclusion: E°cell is positive, so the reaction is feasible. The V3+ formed in step 2 is further reduced.

Observation: The solution will change from green (V3+) to violet (V2+).

Step 4: Final check (V2+ → V)

Identify half-equations:

Oxidation: Zn (s) → Zn2+ (aq) + 2e- (Eθ = +0.76 V)

Reduction: V2+ (aq) + 2e- → V (s) (Eθ = -1.18 V)

Calculate Eθcell:

Eθcell = Eθred - Eθox = (-1.18) - (-0.76) = -0.42 V.

Conclusion: Since Eθcell is negative, this final reduction is not feasible. The reaction stops with V2+.

Final answer summary:

Zinc reduces vanadium from +5 to +2.

The solution will change colour sequentially from Yellow → Blue → Green → Violet.

Common pitfalls:

Mixing up the colours

Simply memorising the colours without linking them to the correct ion and oxidation state.

Incorrect Eθcell calculation

Forgetting that for the reducing agent (Zn), you use its standard electrode potential in the Eθcell = Eθ(right) - Eθ(left) calculation, not the flipped oxidation potential.

Failing to justify

Stating the colour changes without showing the Eθcell calculations that prove each step is feasible.

Equation errors

Forgetting to balance H+ and H2O in the equations for the higher oxidation states.

How to succeed:

Be systematic

Go one step at a time. Start with the highest oxidation state and work your way down, calculating Eθcell for each potential reduction.

Eθcell > 0

Remember this is your golden rule.

A positive Eθcell means the reaction is feasible.

As soon as you hit a negative Eθcell, the sequence stops.

Link everything

Explicitly link each feasible step to the observed colour change:

Eθcell is +1.10V, so the reaction is feasible.

The blue VO2+ is reduced to green V3+

Example 3: Tackling multi-step, unstructured calculations

Examiners love questions that require you to navigate a multi-step calculation where the path isn't obvious. These problems test your ability to connect different chemical concepts under pressure. They separate students who just follow a formula from those who truly understand the principles.

Here’s a great example of a "working backwards" problem from an Edexcel IAL paper:

Mixtures of halide salts are found in brine solutions extracted from oil and gas wells. Iodine, which is used as a dietary supplement, may be obtained from these mixtures.

A brine solution containing 2.49 g of a mixture of potassium iodide and potassium chloride was analysed.

Procedure

Step 1 Excess aqueous silver nitrate solution was added to the solution to completely precipitate the halide ions.

Step 2 Excess aqueous ammonia was added to the mixture.

Step 3 The mixture was filtered, and the solid was washed, dried and weighed.

The mass of the dried solid was 0.162 g.

(ii) Calculate the percentage by mass of potassium iodide in the mixture.

Give your answer to an appropriate number of significant figures.

[Ar values: Ag = 107.9 K = 39.1 I = 126.9]

[3 marks]

[Source: Edexcel IAL Chemistry (WCH12) - Oct 2023, Q19a(ii) (opens in a new tab)]

Why it's tricky:

This is a classic unstructured calculation that requires you to work backwards from a product to a reactant. There is no formula to just plug numbers into.

The Edexcel IAL October 2023 Examiner Report highlights that students struggled with the logical steps required, commenting that many found the procedure "too complex." Instead of following the mole-based logic, some students resorted to confused methods like "dividing the mass of the precipitate by the mass of the original sample."

What the examiner is looking for:

A clear, logical calculation pathway that shows you can connect the mass of a product to the mass of a reactant using moles as the bridge.

Calculate moles of the product (AgI).

Use stoichiometry to determine moles of the reactant (KI).

Calculate the mass of the reactant (KI) from its moles.

Worked solution:

This problem can be solved by creating a clear roadmap:

mass of AgI → moles of AgI → moles of KI → mass of KI

Step 1: Calculate moles of silver iodide (AgI) precipitate

Find the molar mass of AgI:

Mr(AgI) = 107.9 (Ag) + 126.9 (I) = 234.8 g mol-1

Calculate the moles of AgI:

moles = mass / Mr

moles of AgI = 0.162 g / 234.8 g mol-1

moles of AgI = 6.899 x 10-4 mol

Step 2: Use stoichiometry to find moles of potassium iodide (KI)

The relevant reaction is: KI (aq) + AgNO3 (aq) → AgI (s) + KNO3 (aq)

The stoichiometric ratio between KI and AgI is 1:1.

moles of KI = moles of AgI = 6.899 x 10-4 mol

(Note: The potassium nitrate in the original mixture is a spectator ion and does not react.)

Step 3: Calculate the mass of potassium iodide (KI)

Find the molar mass of KI:

Mr(KI) = 39.1 (K) + 126.9 (I) = 166.0 g mol-1

Calculate the mass of KI:

mass = moles × Mr

mass of KI = 6.899 x 10-4 mol × 166.0 g mol-1

mass of KI = 0.115 g (to 3 s.f.)

Calculate the percentage by mass of KI in the 2.49 g sample:

%KI = 0.115 / 2.49 x 100 = 4.60 %

Common pitfalls:

Logical confusion

Feeling overwhelmed by the steps and resorting to random calculations, like dividing masses, as noted in the examiner report.

Molar mass errors

Using incorrect relative atomic masses or making simple addition mistakes.

Stopping too early:

Correctly calculating the moles of KI but forgetting the final step to convert this back into a mass.

Rounding errors

Rounding intermediate values too early, which can affect the accuracy of the final answer.

How to succeed:

Create a roadmap

Before you start, write down the path you will take:

product mass → product moles → reactant moles → reactant mass

This is crucial for unstructured problems.

Show all your steps

Lay out each calculation clearly.

This not only helps the examiner award method marks but also helps you keep your own logic straight.

Use moles as the bridge

Remember that moles are the central currency in chemistry that connects mass, concentration, and stoichiometry.

When in doubt, convert to moles.

Example 4: Interpreting Data & Practical Skills

The hardest practical questions move beyond just doing an experiment. They test your ability to analyse 'the why' behind the method and evaluate the impact of experimental errors on the final result.

This Cambridge International question is a high-level test of this analytical skill:

A student accidentally spilt a little of the residue before carrying out the final weighing.

Predict whether the calculated value of the relative atomic mass of M will be higher or lower as a result of this mistake.

Explain your answer.

[1 mark]

[Source: CIE A-Level Chemistry (9701/32) - June 2023, Q1c]

Why it's tricky:

This question requires a multi-step chain of reasoning. It's not enough to say "the answer will be wrong." You have to trace the procedural error through every step of the calculation to deduce its final effect.

The CIE IAL June 2023 Examiner Report states that only "stronger candidates were able to articulate the effect" and that "weaker candidates did not attempt this question." This shows it is a key discriminator for top students.

What the examiner is looking for:

A clear, step-by-step logical argument that links the practical error to the final calculated value of Ar. They are testing if you understand the entire experimental and calculation process deeply enough to analyse its flaws.

Worked solution:

The key is to "trace the error" through the calculation sequence:

final mass → mass loss → moles of gas → moles of MCO3 → Mr of MCO3 → Ar of M

Step 1: The initial error

Spilling some residue before the final weighing means the measured final mass will be artificially low (lower than it should be).

Step 2: Effect on mass loss

mass loss = initial mass - final mass

Since the final mass is now artificially low, the calculated mass loss will appear artificially high.

Step 3: Effect on moles of gas

The mass loss corresponds to the CO2 that escaped.

moles = mass loss / Mr(CO2)

Since the mass loss is artificially high, the calculated moles of CO2 will be artificially high.

Step 4: Effect on moles of MCO3

MCO3 → MO + CO2

The stoichiometry is 1:1, which means that moles of MCO3 = moles of CO2.

Since the calculated moles of CO2 are artificially high, the calculated moles of MCO3 will also be artificially high.

Step 5: Effect on Mr of MCO3

Mr = initial mass of MCO3 / moles of MCO3

You are dividing the correct, original mass by an artificially high number of moles. Dividing by a larger number gives a smaller result.

Therefore, the calculated Mr of MCO3 will be artificially low.

Step 6: Effect on Ar of M

The final step is:

Ar(M) = Mr(MCO3) - Mr(CO3)

Since the calculated Mr of MCO3 is artificially low, the final calculated value for Ar will be too small.

Common pitfalls:

Getting the logic backwards

Incorrectly assuming spilling residue means less mass loss.

Jumping to a conclusion

Stating "the Ar will be smaller" without providing the step-by-step reasoning to justify it.

Focusing on the wrong values

Getting confused and thinking the initial mass of the sample was affected.

How to succeed:

Trace the Calculation

Write down the sequence of calculations you would perform in the experiment, as shown in the worked solution.

Analyse the first domino

Identify the very first number that the error affects. In this case, it's the final mass.

Follow the knock-on effect

Go through your calculation sequence one step at a time, asking "If this number is now too high/low, how does it affect the next one?"

Example 5: Tackling Synoptic "Levels of Response" Questions

Some of the most daunting questions are the 6-mark "Levels of Response" questions. These aren't just about recalling facts; they test your ability to build a logical, well-structured argument that connects ideas from different parts of the specification.

This Edexcel IAL question is a classic synoptic problem that requires you to act like a chemical detective, using multiple pieces of evidence to solve a puzzle:

Some thermochemical, X-ray diffraction and bromination information on benzene and cyclohexene is shown.

Thermochemical data

Compound | Enthalpy of hydrogenation / kJ mol-1 |

benzene | -208 |

cyclohexene | -120 |

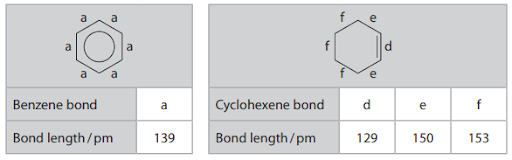

X-ray diffraction

Bromination

Compound | Reaction conditions | Organic product |

benzene | FeBr3, heat | bromobenzene |

cyclohexene | room temperature | 1,2-dibromocyclohexane |

Explain how all this information provides evidence that the electrons in the π-bonds of benzene are delocalised.

[6 marks]

[Source: Edexcel IAL Chemistry (WCH15) - June 2023, Q23 (opens in a new tab)]

Why it's tricky:

This question forces you to synthesise information from three separate areas of chemistry into a single, coherent argument:

Energetics

Bonding

Organic reactions

It's a true test of connected thinking.

The Edexcel IAL June 2023 Examiner Report states that students often failed to make the correct comparisons. For example, many compared the enthalpy of hydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexene, which is irrelevant, instead of comparing it to the theoretical value for a molecule with three isolated double bonds.

What the examiner is looking for:

A well-structured answer that uses each piece of evidence to support the delocalised model of benzene while simultaneously refuting the simple, alternating double-bond (Kekulé) structure.

Worked solution:

For a 6-mark written question, the "solution" is a well-structured plan. Here’s how to build a top-band answer.

Structure your answer around the three pieces of evidence:

1. Thermochemical evidence (Enthalpy of hydrogenation)

Theory: The hydrogenation of cyclohexene (one C=C bond) has an enthalpy change of -120 kJ mol-1. Therefore, the theoretical enthalpy for hydrogenating a Kekulé structure with three C=C bonds (cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene) should be 3 × -120 = -360 kJ mol-1.

Evidence: The experimental enthalpy of hydrogenation for benzene is only -208 kJ mol-1.

Link: Benzene is 152 kJ mol-1 more stable than the theoretical Kekulé structure. This extra stability, known as the delocalisation energy, is evidence for the delocalised pi-system which is not present in the simple triene model.

2. Structural evidence (Bond lengths)

Theory: A Kekulé structure would have alternating short C=C double bonds and longer C-C single bonds.

Evidence: X-ray diffraction data shows that all six carbon-carbon bonds in benzene are of the same, intermediate length.

Link: This experimental evidence directly contradicts the Kekulé model and supports a delocalised structure where the electron density is spread evenly across all six carbons.

3. Reactivity evidence (Reaction with bromine)

Theory: Alkenes (like cyclohexene) contain a localised C=C double bond with high electron density. They readily undergo electrophilic addition with bromine at room temperature, decolourising it instantly.

Evidence: Benzene does not undergo electrophilic addition with bromine under the same conditions. It only reacts in the presence of a halogen carrier catalyst (e.g., FeBr3) and undergoes electrophilic substitution.

Link: The lower electron density of the delocalised ring means benzene is less susceptible to attack by electrophiles. It requires a catalyst to polarise the bromine, and it undergoes substitution rather than addition to preserve the exceptional stability of the delocalised pi-system.

Common pitfalls:

Incorrect comparison

Comparing benzene's enthalpy of hydrogenation to cyclohexene's, rather than the theoretical value for cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene.

Omitting key details

Forgetting to mention the need for a halogen carrier catalyst for benzene's bromination.

Confusing reaction types

Mixing up addition (for alkenes) and substitution (for benzene).

Lack of explicit links:

Stating the facts for benzene and alkenes separately without explicitly explaining how this difference in behaviour provides evidence for delocalisation.

How to succeed:

Use a clear structure

Dedicate a short paragraph to each of the three evidence types. This keeps your argument logical and easy to follow.

Use the "Point-Evidence-Explain" technique

For each paragraph:

Point: State the theoretical expectation for the Kekulé model.

Evidence: Provide the experimental fact for benzene.

Explain: Clearly state how the evidence refutes the Kekulé model and supports the delocalised model.

Use keywords

Make sure to appropriately include key terms like:

Delocalisation energy

Intermediate bond length

Electrophilic substitution

Halogen carrier

Your strategy guide for exam success

Developing a systematic approach to challenging questions dramatically improves your success rate and reduces exam anxiety.

Break down the question

Start by reading the entire question carefully.

Identify what you're actually being asked to find or explain.

Circle or underline key information, data, and command words like "Explain," "Calculate," or "Evaluate."

Always show your working

For calculations:

Write down equations before substituting numbers.

Show all your steps.

Clear working allows examiners to award "error carried forward" marks, so you can still get credit even if you make an early mistake.

Use precise scientific language

Vague language loses marks. Use the precise chemical terms you've learned. For example, explain why phenol is more reactive by referencing the "lone pair on the oxygen atom delocalising into the pi-system." Do not just say it "gives electrons."

Watch the clock

Use the number of marks as a guide for your timing (approx. 1 minute per mark).

If you're stuck on a 2-mark question for five minutes: make your best attempt, flag it, and move on. You can always come back at the end if you have time.

How to practise for the hardest questions

Strategic practice is the secret to turning hard questions into easy marks.

Focus on past papers and examiner reports

Work through challenging questions from your specific exam board under timed conditions. This builds both skill and stamina.

Analyse mark schemes

Don't just check if your answer was right or wrong. The mark scheme reveals the specific phrases and concepts that examiners are looking for. Examiner reports are even better, as they explain the common mistakes students make so you can avoid them.

Target your weak topics

Go through the specification and RAG rate each topic: Red (weak), Amber (okay), Green (confident). Focus your time on turning your red topics to amber. You can find a complete checklist for your exam board in our full guide to A-Level Chemistry Topics by Exam Board.

Build a "tricky questions" list

This is a game-changing revision technique. Every time you get a question wrong in practice:

Write down the question.

Briefly explain why you got it wrong.

Write out the correct approach.

Revisit this list every week. You will quickly turn your weaknesses into strengths.

Putting these strategies into action requires a plan. For a complete guide on how to schedule your revision effectively and use memory techniques, read our step-by-step article on: How to make an A-Level revision timetable.

Frequently asked questions

What are the hardest topics in IAL Chemistry?

While this can vary, our analysis shows that the "hardest" parts of IAL Chemistry aren't always specific topics, but types of questions. The most challenging questions, which consistently appear across both exam boards, are those that require:

Synoptic questions that combine multiple topics (like equilibrium and kinetics).

Multi-step calculations with unfamiliar data.

Complex spectroscopy analysis.

Evaluating experimental procedures and errors.

How do I know if a question is high-level?

High-level questions are less about simple recall (AO1) and more about application and analysis (AO2 & AO3). You can spot them by looking for:

Key command words: "Evaluate," "Compare," "Explain your reasoning," or "Deduce using the data..."

Unfamiliar contexts or scenarios you haven't seen before.

Multiple steps or a high mark allocation (e.g., 6-7 marks).

How can I boost my confidence with hard questions?

Confidence is built through smart, consistent practice.

Start with manageable questions to build momentum before tackling the hardest ones.

Use active recall: Test yourself without looking at your notes.

Teach the concept to someone else. Explaining a difficult topic aloud is the ultimate test of your own understanding and quickly reveals any gaps.

Final thoughts

The hardest International A-Level Chemistry questions are designed to make you think, not just remember. They require genuine understanding, creative application of principles, and sharp analytical skills.

Approaching these questions strategically makes them far more manageable:

Break them down.

Apply systematic methods.

Practice with real past papers and examiner reports.

Don't view difficult questions as a barrier. See them as an opportunity to demonstrate your mastery of the subject. With the techniques in this guide, you'll be ready to tackle them with confidence. You can also read our comprehensive guide on: How to Get an A in A-Level Chemistry.

Now that you're equipped with the expert strategies to deconstruct and master IAL Chemistry's toughest questions, the final step is to put them into practice.

Save My Exams Edexcel International A-Level Chemistry and Save My Exams Cambridge International A-Level Chemistry are the perfect places to do this. Our resources are tailor-made to help you apply these new skills and build exam-winning habits:

Revision notes:

Solidify your understanding of the core principles with our concise, syllabus-aligned revision notes before you tackle the hard questions.

Topic questions & model answers:

Practise the specific types of problems we've covered with our exam-style topic questions.

Each one is created by an expert and comes with a detailed answer, showing you what a top-grade response looks like.

Past papers:

Simulate real exam conditions and perfect your timing with our complete library of past papers and mark schemes from Edexcel International and Cambridge International.

Stop worrying about the hardest questions and start conquering them today.

References:

Cambridge International (CIE), Principal Examiner Report for Teachers, A-Level Chemistry (9701), Paper 41, June 2023 series (opens in a new tab)

Pearson Edexcel, Examiners' Report, International Advanced Level Chemistry (WCH15), Paper 05, June 2023 series (opens in a new tab)

Pearson Edexcel, Examiners’ Report, International Advanced Subsidiary Level In Chemistry (WCH12), Paper 02, October 2023 series (opens in a new tab)

Pearson Edexcel, Examiners’ Report, International Advanced Level In Chemistry (WCH14), Paper 04, January 2024 series (opens in a new tab)

Pearson Edexcel, GCE Chemistry (6CH03), Paper 01, June 2018 series

Sign up for articles sent directly to your inbox

Receive news, articles and guides directly from our team of experts.

Share this article

written revision resources that improve your

written revision resources that improve your