Andropov’s Suppression of Dissidents (Edexcel A Level History): Revision Note

Exam code: 9HI0

Summary

This note will examine how the control of citizens developed after Stalin

Yuri Andropov, head of the KGB (1967–1982), used new and more subtle ways to control opposition

He avoided the mass killings of the Stalin era

Instead using surveillance, intimidation, and punishment to silence critics

People accused of opposing the regime were called 'dissidents'

They included writers, scientists, religious believers, and nationalists

By the early 1980s, the USSR seemed calm on the surface

However, many citizens no longer trusted or believed in the Soviet system

Historians disagree on whether Andropov’s methods kept control effectively, or simply hid growing problems within Soviet society

Who was considered a dissident under Andropov?

'Dissidents' were people who spoke out, even peacefully, against Communist Party control

They had different reasons for their objections to Soviet rule:

Intellectuals

Criticised censorship and wanted more freedom of speech

Andrei Sakharov

Sakharov was a nuclear physicist who demanded respect for human rights

He criticised Soviet actions in Eastern Europe and the arms race

He was placed under internal exile in Gorky (1980) and kept under KGB surveillance

Artists and authors

Exposed problems in Soviet life through books and poems

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Solzhenitsyn revealed the horrors of Stalin’s labour camps in The Gulag Archipelago (1973)

He was expelled from the Writers’ Union and later exiled to the West in 1974

Religious groups

Orthodox Christians, Jews, and Baptists faced restrictions on worship

National minorities

People in Ukraine, the Baltic States, and Poland who wanted independence

Workers

The invasion of Afghanistan (1979) and worsening living standards led to growing frustration among the working classes

Social malaise increased, resulting in poor labour discipline and low productivity

Actions against dissidents under Andropov

Order No. 0051 (1968)

Issued soon after the Prague Spring

The order required the KGB to increase monitoring of “ideological sabotage” and Western influence

It ordered more control over students, writers, and scientists

The order marked the start of a new era of preventive surveillance

Discipline within the KGB

Andropov wanted the KGB to be disciplined, loyal, and uncorrupted

He believed the security service should set an example for the rest of society

KGB officers were:

Banned from accepting gifts or bribes

Expected to live modestly

Dismissed for misconduct, carelessness, or showing political unreliability

Warnings

The KGB focused on prevention by issuing warnings to stop undesirable behaviour

In the 1970s, around 70,000 citizens received warnings

Surveillance and spying

The KGB expanded its network of informants and monitored phone calls and letters

Many people were watched closely, even if they had done nothing illegal

Job loss and social pressure

Dissidents were often fired, blacklisted, or moved to less desirable jobs

Families could lose their homes or be denied university places

Abuse of psychiatry

Some dissidents were declared mentally ill and sent to psychiatric hospitals (psikhushki)

They were diagnosed with “sluggish schizophrenia”

This was a fake illness used to justify their imprisonment

Repressive psychiatry did not have an end term, unlike prison sentences

As a result, people could be held indefinitely

Trials and exile

The government placed famous artists on public trials between 1964 to 1966

In the USSR, citizens needed exit visas to leave the country

For most of the Brezhnev era, Jewish citizens faced strong restrictions on leaving for Israel or the West

Many became known as “refuseniks”, denied permission but punished for applying

Under Andropov, the policy shifted slightly:

Small numbers of Jewish people were granted exit visas, particularly those with family abroad

Andropov argued that this pragmatically removed potential dissidents in the USSR

Many Jewish citizens were working as journalists, scientists, and intellectuals and more likely to disagree with the regime

“Law-and-order” campaign

To combat social malaise, Andropov introduced:

Examiner Tips and Tricks

Compare Andropov's methods with Yagoda's, Yezhov's and Beria's.

Andropov’s KGB had the same goal as previous heads of the secret police but used different methods.

As a result, repression became quieter and more systematic. Consider how this affected dissidence and its contribution to the fall of the USSR.

Impact of Andropov's policies

Short-term effects

The KGB became highly efficient at stopping organised opposition

Open protest almost disappeared, and fear of punishment discouraged people from speaking out

However, the Helsinki Accords (1975) promised to respect human rights

This gave dissidents a legal basis to criticise the government

Long-term effects

Dissent went underground rather than disappearing

Secret publications (samizdat) continued to circulate

Many citizens became cynical

They obeyed publicly but mocked the regime privately

The USSR was stable, but this stability was built on fear, not loyalty

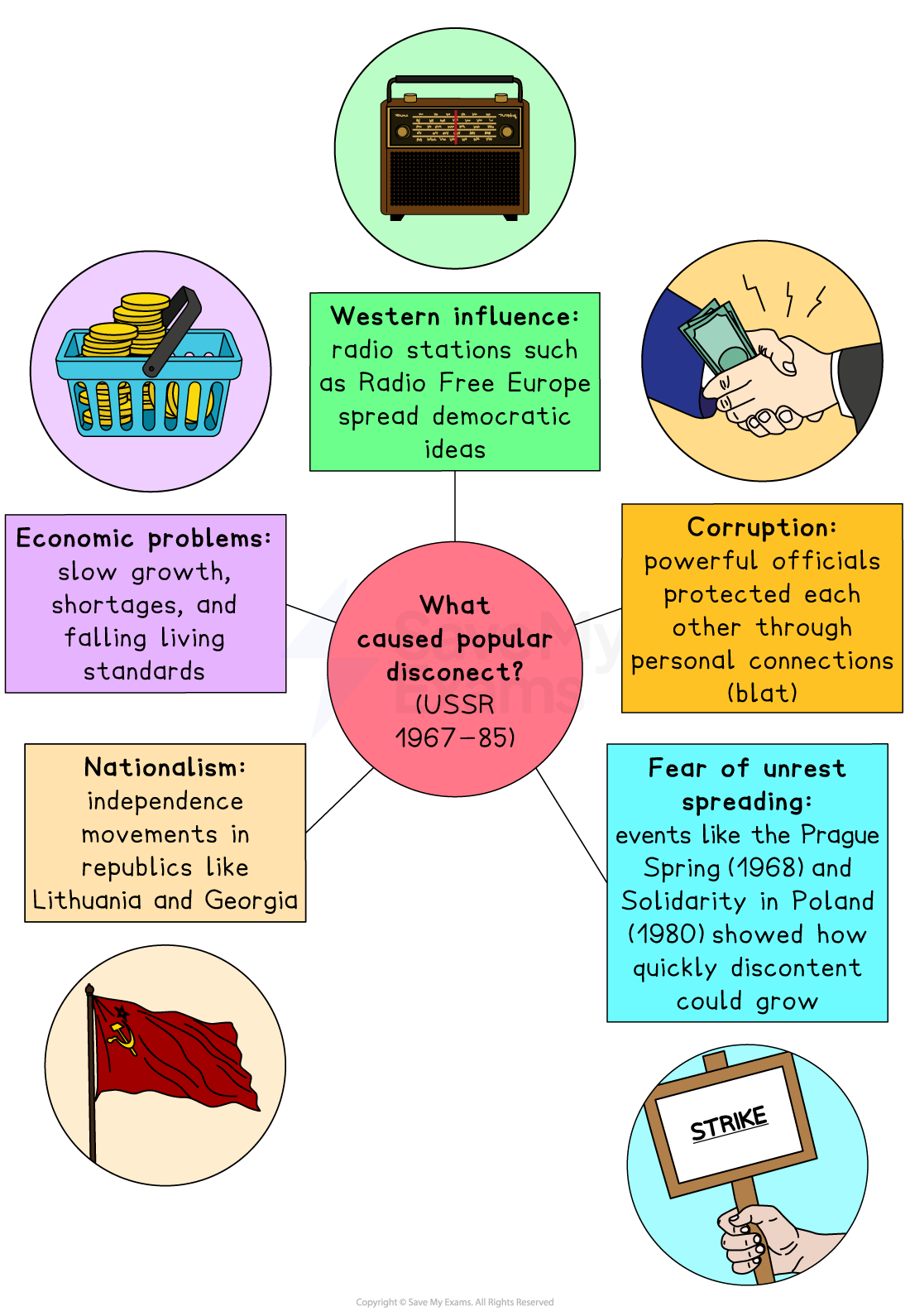

Reasons for the continued monitoring of popular discontent

Could opposition be controlled by 1985?

Historians disagree on whether Andropov’s methods truly kept control or just covered up deeper problems

Andropov's methods kept control

The KGB was professional and efficient

Dissent was small-scale, and society remained stable

Key historians

"By the time Brezhnev died two weeks later on November 10, the succession was a foregone conclusion. Andropov was "unanimously" elected general secretary. Though the Party leadership was unwilling to contemplate major reforms, it was eager to have done with the stagnation and corruption of the Brezhnev era... At this juncture in the Party's history Andropov seemed both a reassuring and an encouraging figure. His treatment of dissidents as chairman of the KGB made it clear that he would have no truck with "ideological subversion"... Andropov's distinguishing characteristic, however, was not sympathy with dissent but greater sophistication in suppressing it." - Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky, KGB: The Inside Story of its Foreign Operations From Lenin to Gorbachev (1990)

"The Soviet Union was not in turmoil. Nationalist separatism existed, but it did not remotely threaten the Soviet order. The KGB crushed the small dissident movement. The enormous intelligentsia griped incessantly, but it enjoyed massive state subsidies manipulated to promote overall loyalty. Respect for the army was extremely high. Soviet patriotism was very strong. Soviet nuclear forces could have annihilated the world many times over. Only the unravelling of the socialist system in Poland constituted an immediate danger, but even that was put off by the successful 1981 Polish crackdown." - Stephen Kotkin, Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970-2000 (2008)

Andropov's methods covered up deeper problems

Although open protest was rare, many citizens had stopped believing in the system

Repression silenced critics

However, it didn’t solve the causes of discontent which were corruption and stagnation

Key historians

"KGB harassment and surveillance kept the dissidents from drawing more supporters from the intelligentsia who sympathized with them... There comes a moment in every old regime where people start to say: 'We cannot go on living like this anymore.' That feeling started in the 1970s. But there was no social force to bring about change. The people were too cowed, too passive and conformist to do anything about their woes. They were more inclined to take to the bottle than the streets. The dissidents had little influence either on the people or on the leadership, but some of their ideas were taken up by reformers in the party, including Gorbachev, who would cite Medvedev's words in justification of his policies of perestroika in glasnost after 1985." - Orlando Figes, Revolutionary Russia, 1891-1991 (2014)

"Dissidence arose among Soviet intellectuals in the 1960s and expanded in the early 1970s. Challenging official policies became possible as Khrushchev loosened state controls, but the practice continued to grown when the boundaries of permissible expression contracted under the Brezhnev administration. It reflected the contradiction between an increasingly articulate and mobile society on the one hand and an increasingly sclerotic political order on the other. While never including more than a few thousand individuals, dissidents exercised a moral and even political weight far exceeding their numbers, and paralleled the self-proclaimed role of the nineteenth-century Russian intelligentsia as the “conscience of society”... But Roy Medvedev’s observation that “There is now a very widespread feeling that the way we live and work has become untenable,” eventually would be repeated by Mikhail Gorbachev as justification for his policies of glasnost and perestroika." - James von Geldern and Lewis Siegelbaum, Seventeen Moments in Soviet History (2015)

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?