Art in the USSR, 1917–1953 (Edexcel A Level History): Revision Note

Exam code: 9HI0

Summary

This note will examine the importance of the arts to the development of the Soviet state

The Bolsheviks saw art as a tool to build socialism, educate the masses, and attack 'bourgeois' culture

Early experiment, such as Proletkult and avant-garde, gave way to tight control under Stalin

From 1932, Socialist Realism became the compulsory style across literature, film, music, and the visual arts

Control of art helped society and glorify leaders, but it also narrowed creativity and created fear

Historians debate whether cultural control was an essential pillar of Soviet power or a costly task that dulled innovation

Bolshevik attitudes to the arts

The new regime treated culture as political work

Art should serve the Revolution, raise literacy, and demonstrate socialist values

However, Bolsheviks disagreed amongst themselves on what proletarian art should be:

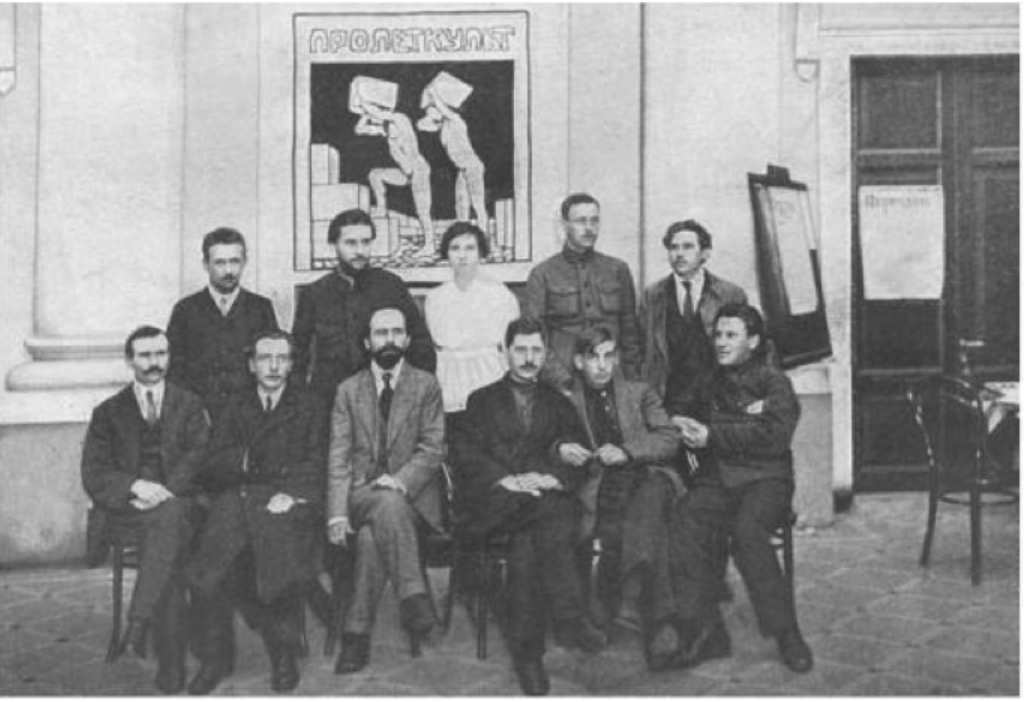

Proletkult

Proletkult stood for “Proletarian culture”

It was a movement to make art by and for workers

Proletkult aimed to create a distinct working-class culture independent of 'bourgeois' traditions

The organisation was independent of the Communist Party

From 1918 to 1920, Proletkult allowed workers to access art studios in order to:

Paint

Sculpt

Write and perform plays

Create exhibitions for their art

Impact of Proletkult

By 1920, Proletkult had around 84,000 members

Proletkult had the support of key Party members, such as Bukharin and Lunacharsky

Members promoted its work even during the Civil War

What caused the end of Proletkult?

Lenin was highly suspicious of Proletkult. He believed it:

Had associations with Futurism, which Lenin hated

Was dominated by 'enemies of the state', such as anarchists

Threatened the success of the Revolution with it being independent from the government

In October 1920, Lenin forced Proletkult to merge with the Commissariat of Education

Examiner Tips and Tricks

In this topic, accurate spelling of key Soviet terms shows strong subject knowledge.

Say the words out loud when revising and write them down three times in your notes as a glossary.

Test yourself on your glossary regularly. You will become comfortable with these spellings, especially in the high-pressure situation of the exam.

Avant-garde & agitprop

What was the avant-garde?

The avant-garde were artists who wanted to revolutionise art

They were experimental with shapes and colours

The government supported avant-garde artists as long as their art helped spread revolutionary ideas

Key avant-garde movements

Constructivism

Founded by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko

Focused on art with a purpose

Posters, buildings, furniture, and designs that were functional and modern

Suprematism

Led by Kazimir Malevich

Used abstract shapes and bold colours to show energy and emotion

Tried to express the spirit of revolution, not everyday life

Film

Sergei Eisenstein used montage to create emotion in films like Battleship Potemkin (1925)

Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) used documentary style to show modern, urban life

Agitprop and its importance

Agitprop was short for “agitation and propaganda”

It was simple, emotional art used to spread political messages

It helped the Bolsheviks educate and inspire the masses, many of whom were illiterate

Features of agitprop

Bright colours

These were often red, black, and white

Simple, bold images and text

Clear, emotional slogans

ROSTA windows

Painted posters shown in shop or factory windows

Used cartoons and short captions to explain revolutionary news

Agit-trains and agit-boats

Travelled across Russia showing posters, films, and short plays

This brought revolutionary ideas to remote villages and factories

Decline of avant-garde

By the late 1920s, critics said avant-garde art was too abstract for workers to understand

The Party began to demand clearer, realistic art showing happy workers and socialism’s progress

This shift led to the rise of Socialist Realism under Stalin in the 1930s

The Cultural Revolution under Stalin

With the First Five-Year Plan, the Party launched a cultural 'offensive' against “bourgeois specialists”

Militant groups (such as RAPP) attacked 'elitist' artists

They demanded 'proletarian content'

Komsomol activists policed theatres and studios

Many professionals were denounced or exiled from the USSR

Socialist Realism

Socialist Realism began to appear in 1930

Stalin pushed for the change in approach to art

Government actions towards Socialist Realism

A decree in April 1932 abolished independent artistic groups

It also created state unions for writers, artists, composers, filmmakers

In 1934, the First Congress of Soviet Writers defined Socialist Realism

It stated that art must be:

Truthful

Historically concrete

Show life as it is and as it should be under socialism: optimistic, heroic, and Party-led

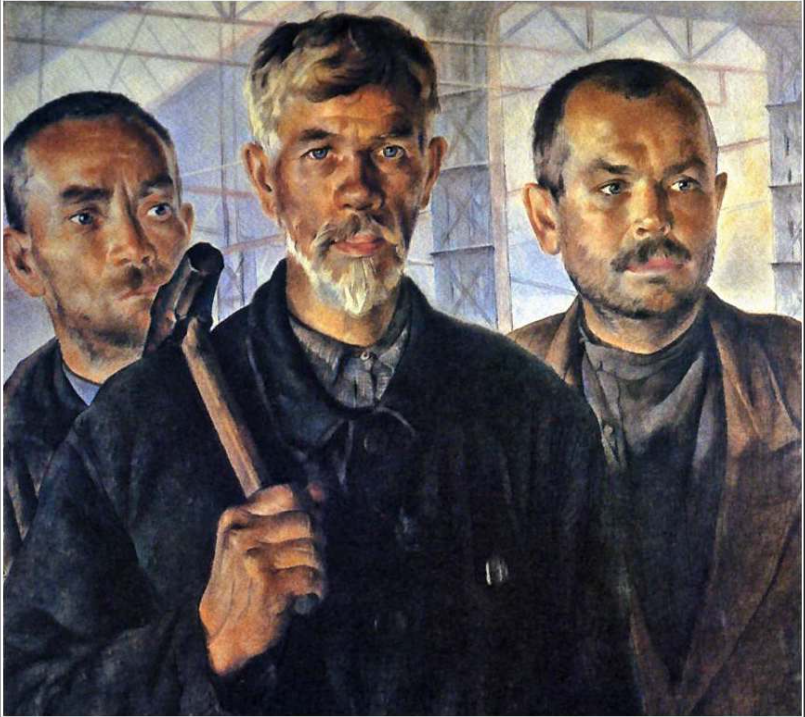

Themes of Socialist Realism

The noble worker

The economic triumphs of collective farm and industrialisation

Victories over class enemies

The cult of personality of Lenin and Stalin

Development of Socialist Realism

Late 1930s

Art became a tool for propaganda, celebrating Stalin and Soviet progress

Paintings showed huge factories and heroic workers

This was called industrial gigantism

Films like Alexander Nevsky (1938, Sergei Eisenstein) mixed patriotism with warnings about foreign enemies

1946–48 – The Zhdanovshchina

After the Second World War, Stalin’s adviser Andrei Zhdanov led a cultural crackdown

Writers like Anna Akhmatova and Mikhail Zoshchenko were banned or publicly criticised

Composers like Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev were attacked for being too experimental

This was called formalism

Stalinist Classicism

A new style called Stalinist classicism took over architecture and public art

Huge, monumental buildings like the Seven Sisters skyscrapers in Moscow symbolised Soviet power

Statues and parades glorified Stalin as a great leader

He became known as the Generalissimo

How important was the control of art to the Soviet government?

Historians debate whether Soviet control of the arts was an important pillar of power or a costly constraint on people's personal and artistic freedom

Art as a pillar of rule

Control created a unified picture of the USSR

Film, posters and literature reached millions with clear, repeated messages

The Party did not constrain creativity

Key historians

"Bolshevism cannot claim credit for the almost mysterious convergence of so many first-rate artists in such a short time; on the other hand, the Bolshevik regime, by setting political goals, did at least partially free some of the directors from commercial considerations. It is unlikely that a capitalist studio would have financed Eisenstein’s first artistic experiments because his work could not possibly have appealed to a large audience. Further, the regime and the artists tacitly cooperated: The regime provided the myths and the artists the iconography. Each benefited... Artists dealt with the pressures differently. Some convinced Bolsheviks naturally made the type of film that was expected of them. Others cared little about ideologies and were perfectly happy to serve any master that allowed them to make films" - Peter Kenez, The Birth of the Propaganda State (1985)

"The Party controlled Culture and Stalin controlled the Party. Involved in this interpretation are some specific propositions and assumptions... Yet in all periods, the relationship between the party and culture was far more complex than a we-they image suggests... If final authority was vested in the party, the party nevertheless delegated, bestowed, or countenanced other types of cultural authority that resided in individuals or cultural institutions. Indeed, the legitimisation of cultural policy was often developed not by reference to party doctrine or the pronouncement of party leaders, but by their reference to non-communist authority figures with status in their own profession, such as Gorky, Stanislavsky, and Pavlov... Certainly, the political leadership was determined to prevent the arts from posing a political or philosophical challenge, or from depicting reality so starkly that a challenge might be provoked. Yet at the same time, leadership's attitude towards many established cultural values was more often deferential than destructive." - Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Cultural Front: Power and Culture in Revolutionary Russia (1992)

Art as constraint

Tight control repressed talent, forced conformity and reduced credibility when art clashed with lived reality

Over time, audiences learned to read between the lines

People also expressed themselves creatively in private or in underground organisations

Key historians

"The approved form of art was Socialist Realism. This meant representational art which was realistic only up to a point. It had to be imbued with optimism and to present an idealised view of workers and peasants. The key word was Socialist in the sense of whatever was currently meant by that term at the top of the Soviet hierarchy. Irreverent Soviet citizens asked: 'What is the difference between impressionist, expressionist and socialist realist art?' The answer: impressionists paint what they see, expressionists paint what they feel, and socialist realists paint what they hear. To listen to the guidance of party and state officials and the guardians of orthodoxy in the state-sponsored artistic unions was the path to a comfortable existence for the artist." - Archie Brown, The Rise & Fall of Communism (2009)

"By the beginning of the 1930s, any writer with an individual voice was deemed politically suspicious. The Five Year Plan was not just a programme of industrialization. It was a cultural revolution in which all the arts were called up by the state to build a new society. According to the plan, the duty of the Soviet artist was to raise the workers’ consciousness, to enlist them in the ‘battle’ for ‘socialist construction’ by producing art with a social content which they could understand and relate to as positive ideals...But in Stalin's version of the doctrine, as pleased by the regime's cultural institutions after 1934, it imposed a deadening conformity on artists and writers, who were now expected to be uniformly optimistic about Soviet life and easily accessible to the masses. They were meant to be the chronicles of a milestone narrative - the progress of humanity towards the Communist Utopia - defined for them by the state." - Orlando Figes, Revolutionary Russia, 1891-1991 (2014)

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?