Control of Mass Media in the USSR (Edexcel A Level History): Revision Note

Exam code: 9HI0

Summary

This note will examine the power of mass media in the Soviet state

From Lenin to Chernenko, the Soviet state kept tight control over newspapers, radio, television, and cinema

Media was used to spread propaganda, promote leaders’ cults of personality, and restrict access to alternative viewpoints

Control meant that communist ideology was always presented as the official truth

However, many citizens became sceptical

They knew newspapers, radio, and television were heavily censored and did not reflect everyday reality

Historians debate whether controlling the media strengthened Soviet stability or weakened it by alienating the public

Soviet control of newspapers & magazines

Lenin (1917–1924)

Bolsheviks shut down opposition papers immediately after taking power

Printing presses were nationalised

Pravda ('Truth') became the Party’s main newspaper

It presenting Bolshevik ideology and attacking class enemies

Glavlit

Stood for the Main Administration for Literary and Publishing Affairs

Created in 1922, it was the official state censorship body

Every book, article, and film script had to be approved by the GPU before publication

Controlled not just politics but also sensitive scientific topics (such as nuclear physics)

'Book Gulags'

Banned or politically sensitive books were removed from general circulation

Some were kept in special 'Book Gulags'

These were closed sections of libraries

Access was tightly controlled, usually only granted to:

Academics with special permission

Party officials

Stalin (1928–1953)

Newspapers like Pravda and Izvestiya reported successes of Five-Year Plans

The news credited Stalin will all of the achievements of the regime

Heroic workers were celebrated daily

The media ignored famine, purges, or defeats

'Bad news' was bad or blamed on saboteurs

From 1928, Glavlit controlled access to all economic data

Khrushchev (1953–1964)

In the 1950s–60s, a small degree of media pluralism emerged

The regime allowed more lifestyle and consumer-focused magazines

These were not politically critical but offered practical content, showing a shift towards meeting public demand

For women

Magazines such as Rabotnitsa ('The Woman Worker') targeted female readers

Offered advice on:

Childcare

Cooking

Health

Fashion

Readers highlighted significant social issues in the USSR, such as:

Male alcoholism

Domestic inequalities

Domestic violence

In response, Khrushchev launched a propaganda campaign against 'worthless men' who were not 'dedicated to communism'

This reflected Khrushchev’s promises to improve living standards and family life

Satire and humour

Krokodil, a satirical magazine, mocked inefficiency, corruption, and minor social problems

It was tightly censored and never criticised Party leaders

It acted as a 'safety valve' for public frustration

Allowed readers to laugh at everyday absurdities while reinforcing loyalty to the state

Brezhnev to Chernenko (1964–1985)

Leaders lost control of publications

Western magazines became increasingly common in Soviet cities

Popular magazines included Vogue

These showed the level of consumerism in the West, undermining the Soviet system

Examiner Tips and Tricks

When writing about Soviet control of the media, don’t just list policies or examples for each leader.

Examiners want to see that you can identify long-term trends as well as short-term changes. For example, across the whole period, one major continuity was that censorship never disappeared. However, within that, there were clear shifts, such as Khrushchev briefly loosened control with more “human” films and consumer magazines.

By showing both continuity and change, you demonstrate a higher-level understanding of the topic.

Soviet control of the radio

Lenin and Stalin

Radios were mass-produced from the 1920s as a cheap way to spread propaganda

Radios were deliberately made with limited tuning capacity, so they could only receive state stations

Popular in rural areas where literacy was low

Khrushchev and Brezhnev

Loudspeakers placed in public spaces, broadcasting news and Party speeches

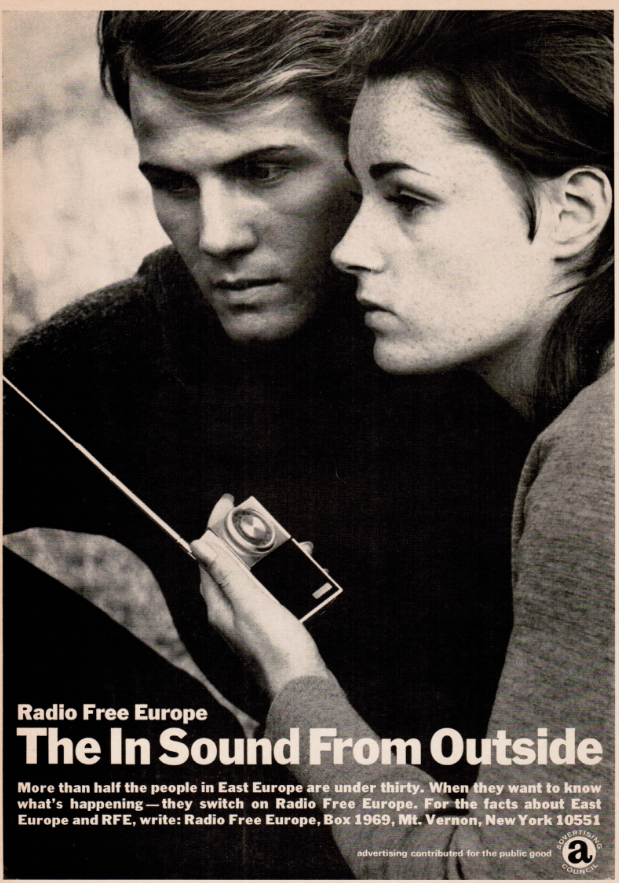

Foreign broadcasts like Radio Free Europe and Voice of America tried to reach Soviet audiences with alternative information

The USSR used jamming technology to block these signals, though some citizens found ways to listen secretly

Despite censorship, radio remained an effective propaganda tool due to its speed and wide reach

Soviet control of the cinema

Lenin

Lenin declared: “Of all the arts, cinema is the most important”

Films could reach illiterate peasants and spread ideology

Early silent films showed revolutionary struggle

They vilified the Whites in the Civil War

Newsreels were widely shown in towns and villages to spread Bolshevik victories

Stalin

Cinema became a central part of Socialist Realism

Films glorified industrialisation and collectivisation, portraying workers and peasants as heroes

Stalin’s cult of personality dominated

Films like The Fall of Berlin (1950) celebrated Stalin's greatness during the Second World War

Leaders appeared as wise, fatherly figures guiding the USSR to greatness

Khrushchev

De-Stalinisation and the Thaw brought more freedom in cultural life, including cinema

Filmmakers explored ordinary people’s experiences, everyday struggles, and emotional lives, moving away from Stalinist hero-worship

The Forty-First (1956)

A war film focusing on a female soldier and her doomed romance with a captured White officer

It highlighted personal stories, not just Party triumphs

Ballad of a Soldier (1959)

Portrayed a young soldier’s humanity and sacrifice

It emphasised individual experience in war

Brezhnev

The cultural thaw ended; censorship tightened again

Cinema shifted back to safe and conservative genres, such as:

Historical epics

Patriotic war films

However, Brezhnev also encouraged films that showcased consumer aspirations and luxury lifestyles

The Irony of Fate (1975) was a romantic comedy satirising Soviet housing blocks

However, it showed aspirational modern living

Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1980) followed three women in Moscow chasing careers, love, and consumer success

It portrayed Soviet modernity and the dream of a 'better life'

Soviet control of television

Early growth under Khrushchev (1950s–1960s)

Television spread rapidly in the USSR

By the early 1960s, most towns had access to state-controlled channels

Programming often celebrated scientific and technological triumphs, especially the space race

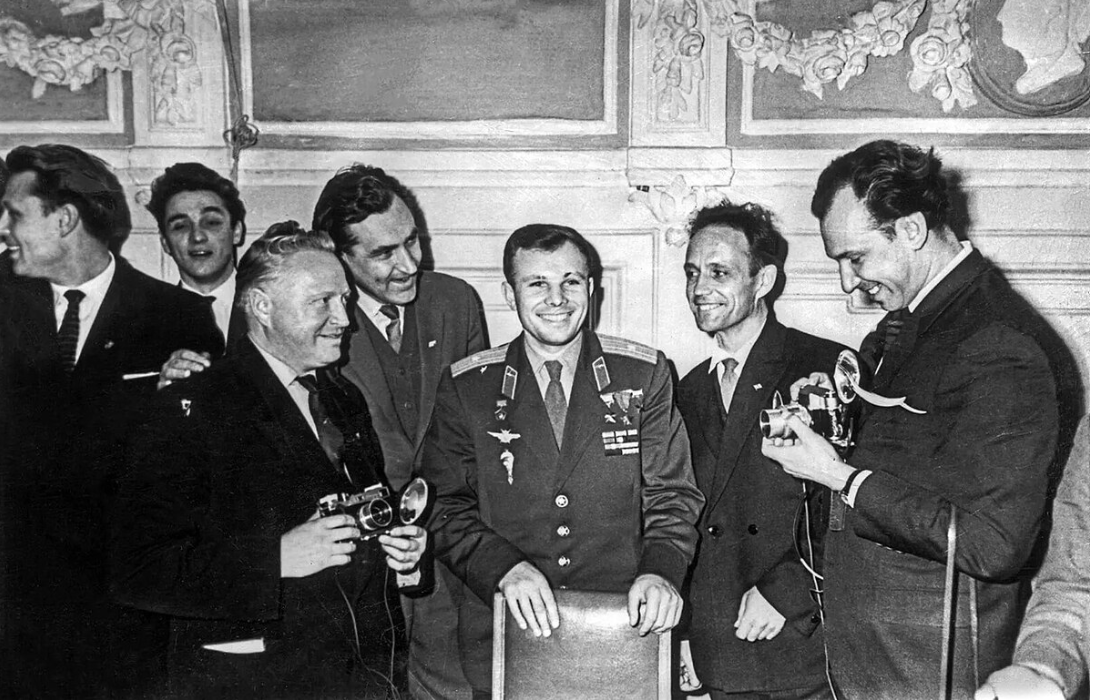

Coverage of Yuri Gagarin’s spaceflight (1961) made him a national and international hero

Gagarin’s smiling face was shown repeatedly, symbolising Soviet progress and superiority

Brezhnev (1964–1982)

Propaganda and news programming

Television became the most popular medium for Soviet citizens, overtaking newspapers

Estafeta Novostei (News Relay) was a central news programme

It provided highly controlled coverage of Soviet achievements and downplayed or ignored crises

News reports consistently presented the USSR as stable, strong, and united, reinforcing Brezhnev’s “era of stability”

The War in Afghanistan (1979–1989)

The invasion of Afghanistan was heavily censored on television

Official broadcasts described it as “internationalist duty” to support Afghan communists, avoiding mention of Soviet casualties

Families often found out about deaths through unofficial networks, fuelling public cynicism about TV propaganda

Brezhnev’s declining health

From the late 1970s, Brezhnev appeared regularly on television at Party congresses and official events

His physical decline was obvious as he had:

Slurred speech

An inability to walk unaided

A reliance on notes

Instead of reassuring the public, these broadcasts reinforced the sense of stagnation and decline in the USSR

Impacts of Soviet control of mass media

Strengthened control

Promoted cults of personality for Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev

Gave the Party a powerful propaganda tool, especially in highlighting Soviet victories

Created scepticism

Citizens knew major problems (famines, corruption, shortages) were ignored

Informal information networks and samizdat (self-published literature) grew as alternatives

By the 1970s, trust in official media had declined sharply

Did controlling the media help or hinder the USSR?

Historians disagree whether media control was a source of stability or a weakness that bred cynicism

Media control helped maintain stability

Control over newspapers, radio, and TV allowed the Party to dominate public life

Achievements (like space exploration) were turned into propaganda successes

Key historians

"The problem of understanding is all the greater because of the distance between the utopian vision and Soviet reality. It is tempting to dismiss the vision as simply deception and camouflage, especially since the utopian rhetoric actually did serve those purposes, among others, for the Soviet regime. But the vision cannot be dismissed in a study of everyday Stalinism. Not only was it a part of Stalinism, and an important one at that, but it was also a part of everyone’s everyday experience in the 1930s. A Soviet citizen might believe or disbelieve in a radiant future, but could not be ignorant that one was promised" - Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times (1999)

"By greatly increasing the numbers of people who could read, the Communist Party ensured that there was a wider audience for its written propaganda. A fundamental part of Stalinist propaganda was the virtual deification of Stalin... It had a number of purposes, including linking Stalin to the country's achievements and portraying him as Lenin's heir...Soviet propaganda presented a picture which had some grains of truth in it. And while remembering the horrors that Stalinism brought to many, it must also be acknowledged that some people benefited from the system." - Jonathan Davis, Stalin from the Grey Blur to Great Terror (2008)

Media control weakened the regime

Heavy censorship widened the gap between propaganda and reality

Citizens increasingly dismissed state media, undermining its effectiveness

Key historians

"Many people were disenchanted with the Soviet system. But few were brave enough to join the dissidents or oppose it openly. They might tell anti-Soviet jokes to let off steam in private. But they were unlikely to voice opposition views openly. This political conformity lies behind the stability of the Soviet system in its final years, when few people believed actively in the revolution's goals or propaganda claims. To explain it we must look at Soviet history and consider how the memory of repression formed what people called 'genetic fear'." - Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy (1996)

"In the only significant study of Soviet propaganda, Peter Kenez argues in a similar vein that the regime

succeeded in preventing the formation and articulation of alternate points of view. The Soviet people ultimately came not so much to believe the Bolsheviks' worldview as to take it for granted. Nobody remained to point out the contradictions and even innateness in the regime slogans.

These conclusions are undermined by the new sources, which reveal that, on the contrary, ordinary people were adept at defeating the censor, seeking out alternative sources of information and ideas in the form of rumours, personal letters, leaflets (listovki), and inscriptions (nadpisi). They also continued to draw on a variety of rival discourses, including those of nationalism, anti-Semitism, and populism, which proved tenacious despite concerted attempts to eradicate them." - Sarah Davies, Popular Opinion in Stalin's Russia: Terror, Propaganda and Dissent, 1934-1941 (1998)

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?