The Treatment of Opponents in the USSR (Edexcel A Level History): Revision Note

Exam code: 9HI0

Summary

This note will examine the terror state in the Soviet Union

The USSR developed one of the most extensive systems of surveillance and repression in the 20th century

From Lenin’s Cheka to Brezhnev’s KGB, the secret police evolved into a pillar of Soviet control

The GULAG system became a vast network of forced labour camps used for punishment and production

Show trials and purges reinforced fear and loyalty to the Party

Historians debate whether repression was necessary to protect the revolution or an abuse of power that destroyed trust

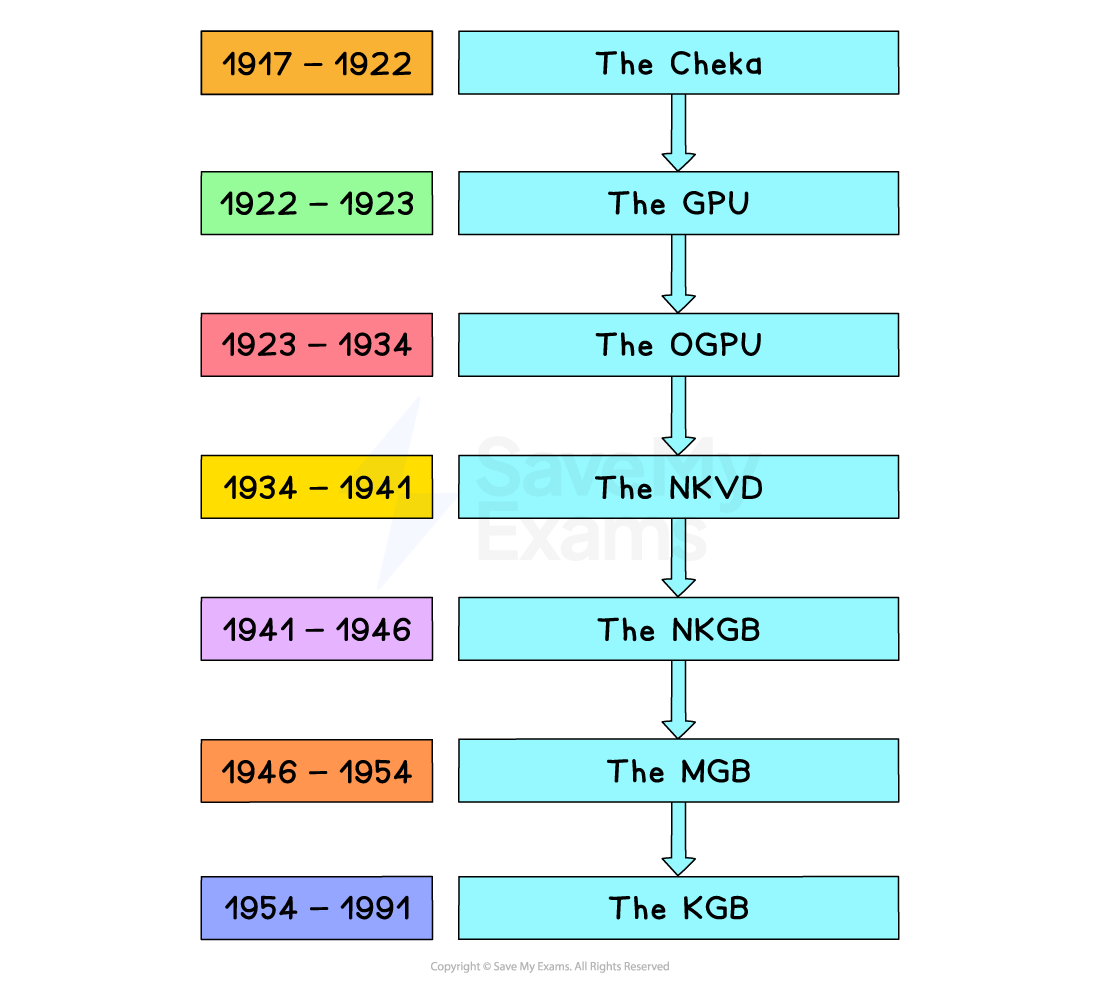

The development of the secret police

From 1917–85, the secret police changed names but not purpose

They protected the Communist Party from:

Internal and external enemies

Real and fictional threats to their rule

Cheka

Stood for: All-Russian Extraordinary Commission

Leader: Felix Dzerzhinsky

Purposes

Suppress counter-revolution and sabotage

Carry out the Red Terror during the Civil War

Reason for dissolution

Replaced by GPU in 1922 to make the organisation appear more legal and permanent after wartime terror

GPU and OGPU

Stood for: (Unified) State Political Directorate

Leaders: Felix Dzerzhinsky (1922–1926) and Vyacheslav Menzhinsky (1926–1934)

Purposes

Oversaw early labour camps and internal security

Investigated 'wreckers' and political suspects during NEP

Reason for dissolution

Merged into NKVD in 1934 to increase Stalin’s control and coordinate police, security, and labour camps under one organisation

NKVD

Stood for: People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs

Leaders: Genrikh Yagoda (1934–1936), Nikolai Yezhov (1936–1938), Lavrenti Beria (1938–1941)

Purposes

Conducted the Great Purges and ran the GULAG system

Handled foreign espionage and internal deportations

Reason for dissolution

Split in 1941 to form the NKGB to separate state security from general policing after the purges

NKGB and MGB

Stood for: People’s Commissariat / Ministry for State Security

Leader: Lavrenti Beria

Purposes

Similar roles to the NKVD

Reformed during the war to focus on counter-intelligence, deportations, and political control in newly occupied territories

Reason for dissolution

Dissolved after Stalin’s death and Beria’s execution as part of Khrushchev’s effort to reduce terror

KGB

Stood for: Committee for State Security

One of its key leaders was Yuri Andropov (1967–1982)

Purposes

Focused on domestic surveillance, dissident suppression, and foreign intelligence

Under Andropov, the KGB became highly professional and effective

Reason for dissolution

Collapsed with the USSR’s fall

The GULAG system

First appeared under Lenin’s Cheka as labour camps for 'class enemies'

The GULAG aimed to:

Severely punish criminals

Deter other citizens from committing crimes

Provide the state with free labour

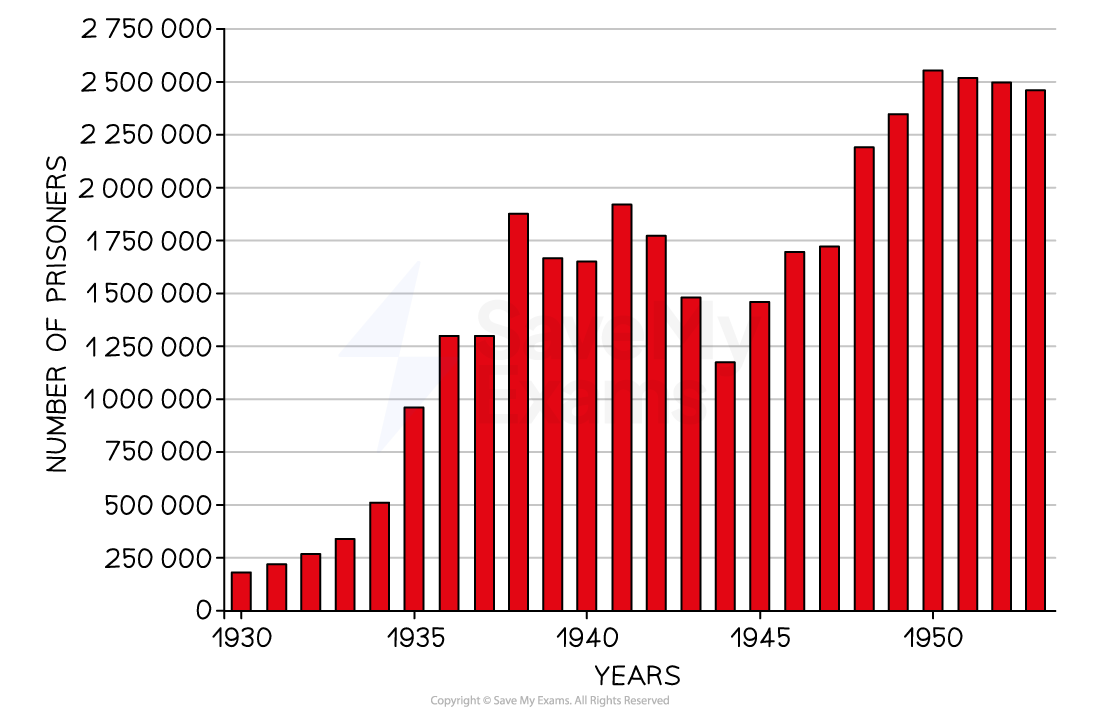

Expanded massively under Stalin:

By the early 1950s, around 2.5 million people were imprisoned in camps

Located mainly in remote areas like Siberia and the Arctic, where prisoners were used as forced labour

Prisoners included:

Political opponents

Kulaks and NEPmen

Workers accused of sabotaging

Members of the military

Artists who broke censorship

Out-of-favour Party members

Conditions were brutal. Prisoners suffered:

Food shortages

Disease

Exhaustion

Freezing temperatures

As a result, there were high mortality rates in the camps

Despite Khrushchev’s de-Stalinisation, labour camps still existed

They continued on a smaller scale until the late 1980s

Examiner Tips and Tricks

Students often use 'gulag' as if it means a single camp. Even some historians use the term 'gulag'.

GULAG stands for the 'Main Camp Administration'. It was a system of thousands of camps run by the state.

Think of it like the NHS. Each labour camp (hospital) was part of the larger GULAG system (the NHS).

Using this distinction in an essay shows real understanding of the period.

Show trials in the USSR

The show trials were a key feature of Stalin’s terror in the 1930s

They were public trials of senior Party members designed to:

Remove political opponents

Justify the purges

Demonstrate loyalty to Stalin and the “unity” of the Communist Party

Defendants were forced to confess through:

Torture

Threats

The arrest of their family members

Trials were widely reported in newspapers, ensuring that the public believed in Stalin’s narrative of 'enemies of the state'

The Trial of the Sixteen (1936)

Also known as the First Moscow Trial

Purpose: To eliminate Stalin’s early rivals and send a warning to the Party

Key figures: Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, and 14 others (old Bolsheviks and early Party leaders)

Accusations: Forming a “Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Centre” to assassinate Stalin and restore capitalism

Outcome: All found guilty and executed

The Trial of the Seventeen (1937)

Also known as the Second Moscow Trial

Purpose: To extend the purges beyond the top level, targeting administrators and industrial specialists

Key figures: Karl Radek, Georgy Pyatakov, and other middle-ranking Party and economic officials

Accusations: Industrial sabotage, spying for Germany and Japan, and plotting with Trotsky

Outcome: 13 executed, the rest sent to labour camps

The Trial of the Twenty-One (1938)

Also known as the Third Moscow Trial

Purpose: To eliminate the last of Stalin’s potential rivals and the Right Opposition, completing the purge of the Old Bolsheviks

Key figures: Nikolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Christian Rakovsky, and 18 others

Accusations: Treason, espionage, 'wrecking', and plotting to overthrow socialism

Outcome: All executed

Was the Soviet police state justified?

Historians disagree on whether the police state was necessary to protect the revolution or if it became a tool of terror and personal rule

The police state was justified

Supporters argue the USSR faced genuine threats from civil war, sabotage, and foreign enemies

Repression was a harsh but necessary defence of socialism

Key historians

"In Tsarist days political offenders had enjoyed certain privileges and been allowed to engage in self-education and even in political propaganda. Oppositional memoranda, pamphlets, and periodicals had circulated half freely between prisons and had occasionally been smuggled abroad. Himself an ex-prisoner, Stalin knew well that jails and places of exile were the 'universities' of the revolutionaries. Recent events taught him to take no risks. From now on all political discussion and activity in the prisons and places of exile was to be mercilessly suppressed; and the men of the opposition were by privation and hard labour to be reduced to such a miserable, animal-like existence that they should be incapable of the normal processes of thinking and of formulating their views." - Isaac Deutscher – Stalin: A Political Biography (1949)

"When the military-revolutionary committee was finally dissolved this section remained, and, by a decree of Sovnarkom of December 7/20, 1917, was reorganized as “the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ” (Cheka for short) for the purpose of “combating counter-revolution and sabotage”... At the critical moment of a hard-fought struggle, the establishment of these organs can hardly be regarded as unusual. Within six weeks of the revolution, Cossack armies and other "white" forces was already mustering in south-eastern Russia; the Ukraine, aided on by French and British promises, was in a state of all but open hostilities against the Soviet power; the Germans, in spite of the armistice, were a standing threat in the West. The military danger made it essential to bring order out of chaos at home." - E.H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution (1950)

The police state was unjustified

Other historians believe that repression destroyed trust, creativity, and efficiency, replacing genuine loyalty with fear

Millions suffered unnecessarily in purges and camps

Key historians

"The rationale of the Soviet Police has always been that it is the ‘Sword of the Revolution’... It has so far been the rule that the power and activity of the police have increased enormously during periods of crises in the Soviet Union, whether spontaneous or created by official policy (like the collectivisation terror). The first wave, starting in 1918 and culminating in the terror against the Kronstadt rebels, was followed by a period of comparative civic peace and stability, in which the Police’s role, though never unimportant, was far less obtrusive. In 1930 came the collectivisation campaign which, by the beginning of 1933, left Police and Party victorious at the cost of the lives of millions of the peasantry. The Yezhov Terror in 1936-38 involved the use by Stalin of the NKVD as in effect his only weapon in destroying the old Party, disrupting all non-Stalinist loyalties, and packing the labour camps with millions of innocent citizens...In the new society Stalin created, police activity was no longer an emergency operation, but thoroughly institutionalised. After the death of Stalin, the surviving leadership showed some wish both to curb the Police in its capacity as a political entity dangerous to themselves, and to relax pressures in the hope that Soviet society would have achieved its own stability without needing too much in the way of coercion. But towards the end of Khrushchev’s tenure, and since, the Police have again tended to play an independent role. The KGB not only has its own professional interest in repression, but has also shown itself to be an important component of the ‘reactionary’ tendency in Soviet politics." - Robert Conquest, The Soviet Police System (1968)

"What did people think when a husband or a wife, a father or a mother was suddenly arrested as an ‘enemy of the people’? As loyal Soviet citizens how did they resolve the conflict in their minds between trusting the people they loved and believing in the government they feared?... By conservative estimates, approximately 2.5 million people were oppressed by the Soviet regime between 1928, when Stalin seized control of the party leadership, and 1953, when the dictator died, and his reign of terror, if not the system he had developed over the past quarter of a century, was at last brought to an end... In addition to the millions who died or were enslaved, there were tens of millions, the relatives of Stalin's victims, whose lives were damaged in disturbing ways, with profound social consequences that are still felt today. After years of separation by the Gulag, families could not be reunited easily; relationships were lost; and there was no longer any normal life to which people could return... In a society where it was thought that people were arrested for loose tongues, families survived by keeping to themselves. They learned to live double lives, concealing from the eyes and ears of dangerous neighbours, and sometimes even from their own children, information and opinions, religious beliefs, family values and traditions, and modes of private existence that clashed with Soviet public norms. They learned to whisper." - Orlando Figes, The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia (2007)

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?