Agricultural Collectivisation (Edexcel A Level History): Revision Note

Exam code: 9HI0

Timeline & Summary

This note will examine the implementation of collectivisation in the Soviet state

Stalin launched collectivisation to modernise farming, secure grain supplies, and strengthen state control over the countryside

It involved merging small peasant farms into large collective farms and removing kulaks as class enemies

While it secured grain for the cities and exports, it caused famine, resistance, and millions of deaths

Historians remain divided over whether collectivisation was necessary modernisation or reckless destruction

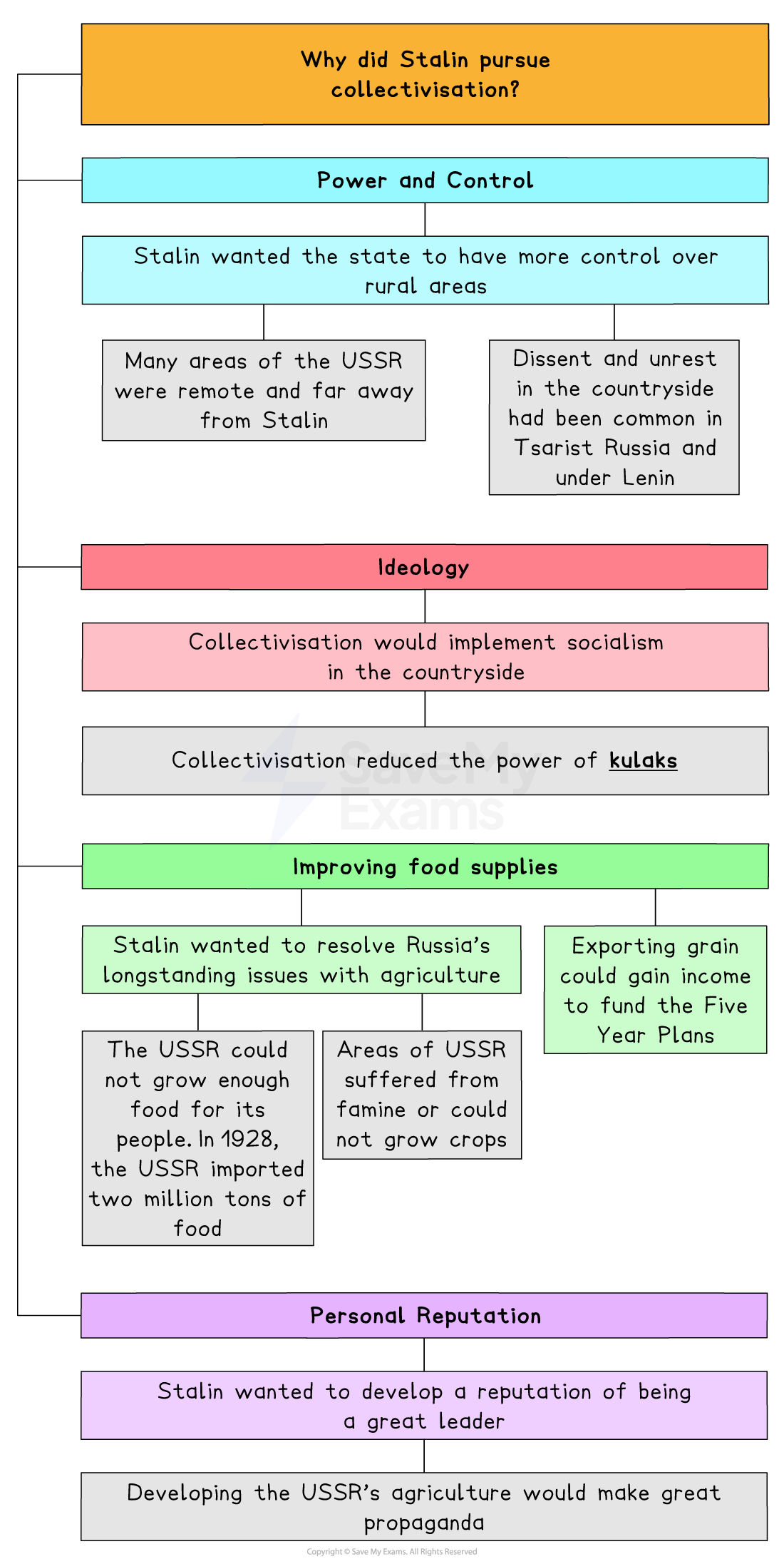

Reasons for collectivisation

While the Five-Year Plans focused on rapid industrialisation, collectivisation aimed to improve agricultural output

Stalin introduced the concept in 1928

There are many motivations behind collectivisation

Examiner Tips and Tricks

Students sometimes believe that collectivisation and Five-Year Plans are the same policy. They both began in 1928, but they targeted different sectors of the economy. The Five-Year Plans focused on rapid industrialisation. Collectivisation aimed to increase the efficiency of agriculture. The methods used for each policy are also different.

The process of collectivisation

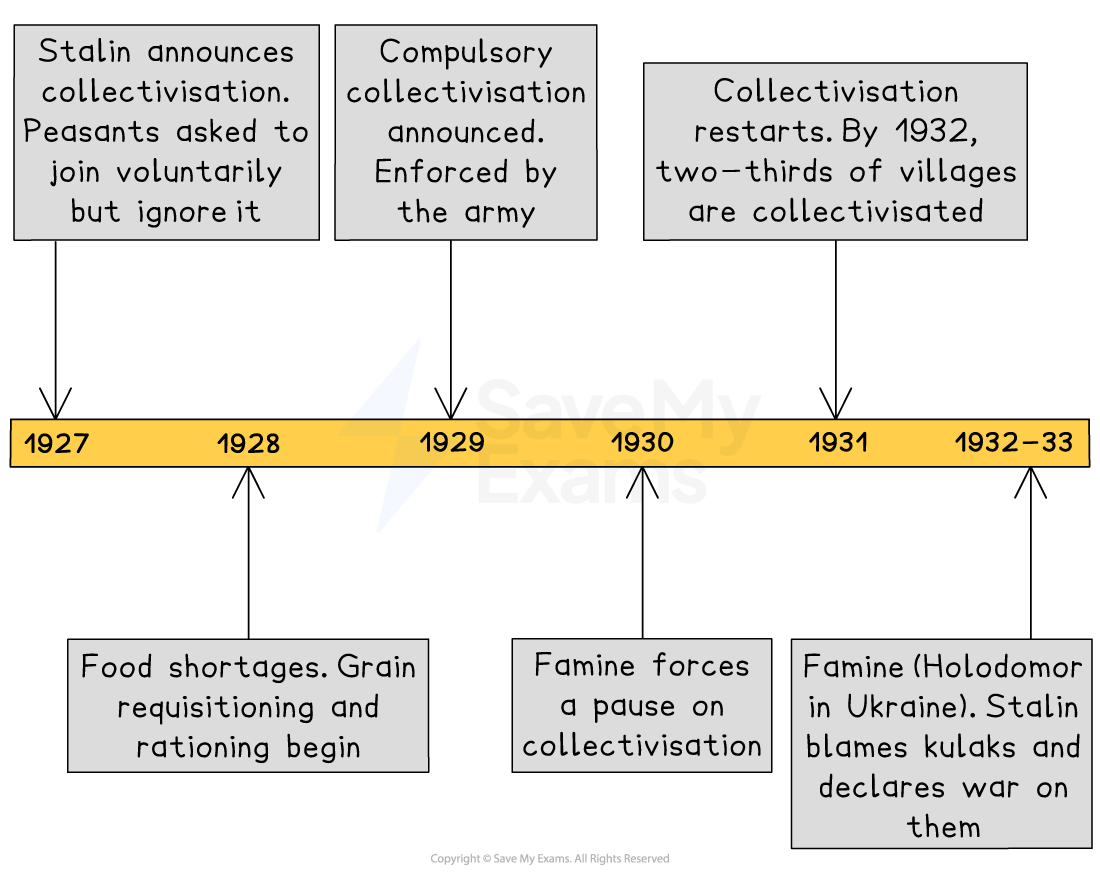

Stalin was forced to introduced collectivisation in two stages

Stage one

Increase the mechanisation of farming and bring the peasants under government control

Stage two

The slowing down of collectivisation and the introduction of Machine Tractor Stations (MTS)

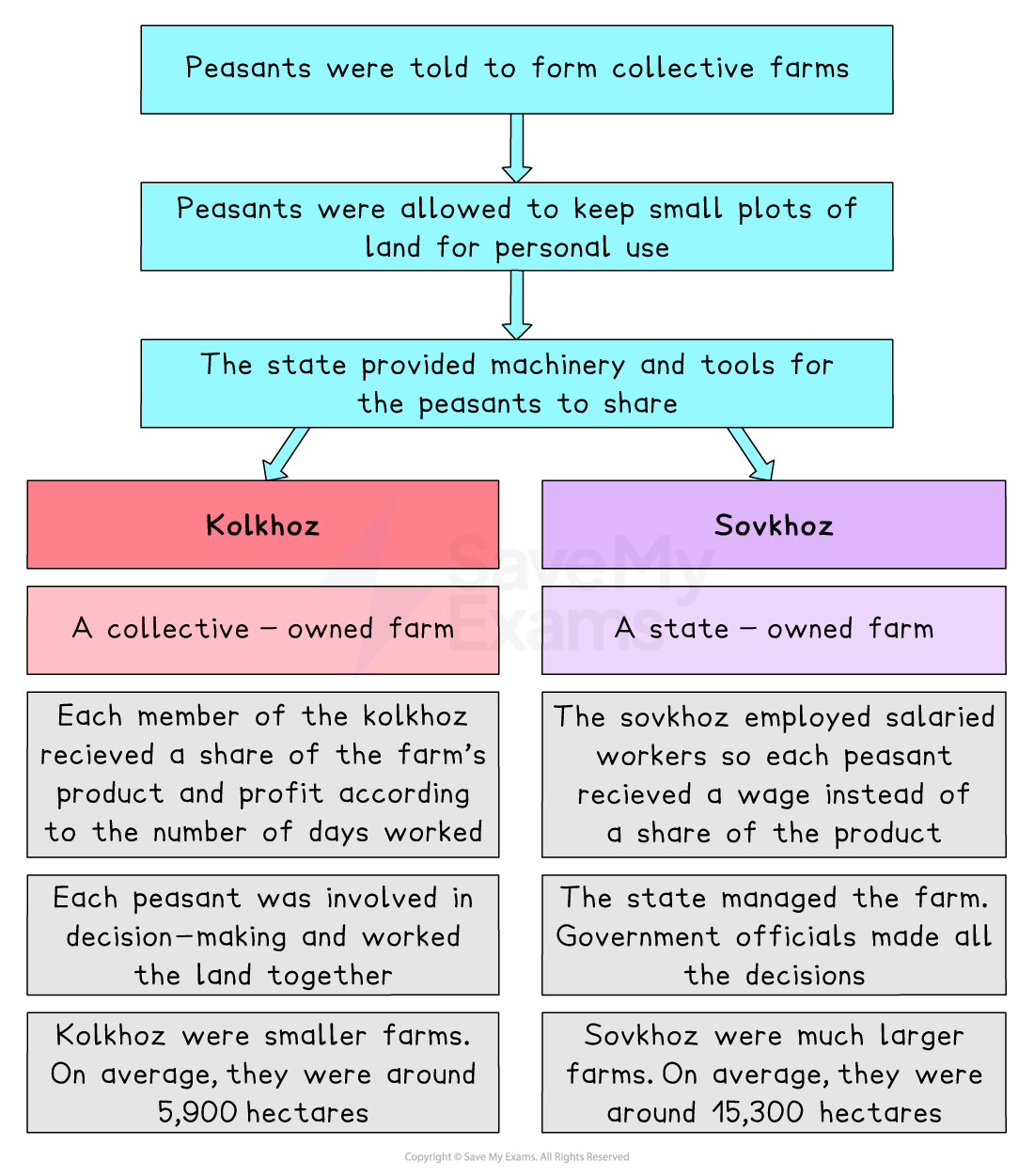

How did collectivisation work?

Dekulakisation

Reasons

Peasants reacted angrily to grain requisitioning and forced collectivisation by:

Attacking officials trying to collectivise farms

Destroying or hiding crops

Killing livestock

The government began blaming kulaks for these actions

Stalin launched a 'liquidation' campaign against the kulaks as a class

This is otherwise known as dekulakisation

Results

Thousands were executed

Around 1.5 million were deported to Siberia or to labour camps

Impacts of collectivisation

Economic

Positive impacts

Grain exports rose, helping to finance industrialisation

In 1928, the USSR exported less than 1 million tons of grain

By 1931, this was 5 million tons

Farming was known widely mechanised

Negative impacts

Agricultural productivity remained low

Collective farms produced 320 kilos of grain per hectare

Private farms produced 410 kilos

There was no incentive for peasants to work hard

Dekulakisation removed the most experienced farmers

Harvests remained poor, causing famine

Livestock numbers took decades to recover

Social

Resistance

Peasants continued to rebel

Peasants destroyed crops and animals rather than hand them over to the government

The Holodomor (1932–33)

Collectivisation had damaging impacts on Ukraine

Ukraine was a profitable agricultural region of the USSR

It grew a vast amount of grain

Ukraine fought back against collectivisation

Ukraine had a strong cultural and national identity

The government punished Ukrainian peasants

They violently repressed the peasants who refused to collectivise

In 1932, they increased the government quota for grain, despite there being a poor harvest

The government's actions caused the Holodomor

This means 'death by hunger'

The government took all food from peasants who could not meet their quota

The exact number of deaths is unknown, but it is within the millions

Political

The state established firm control over the countryside

By 1939, 99% of peasant households had been collectivised

Party officials and MTS workers monitored villages closely

Examiner Tips and Tricks

Try to make comparisons across the course to deepen your understanding. How did the results of collectivisation compare to War Communism and the NEP?

Try to make comparisons based on multiple categories, such as:

Productivity

Ideology

Social and political impacts

How damaging was collectivisation to the USSR?

Historians disagree whether collectivisation was a brutal necessity for modernisation or a catastrophic policy that undermined the USSR

Collectivisation as necessary for modernisation

Some argue collectivisation:

Secured grain for cities

Provided exports to fund industry

Allowed the USSR to prepare for war

They stress its role in enabling the Soviet Union to industrialise rapidly in the 1930s

Key historians

"Within ten years the collective farms were producing significant results. Grain crops were thirty to forty million tons higher than under individual farming. Industry had begun to supply the tractors and combine harvesters to give Russian farming a high degree of mechanization. Large numbers of men and women had been trained to drive tractors and to manage collective farms. All opposition had been crushed and two million Kulaks, deprived of their property and debarred from the new collective farms, had been deported to Siberia or found themselves in forced labour camps." - P.J. Larkin, Revolution in Russia (1965)

"The collective farms, despite all their inefficiencies, did grow more food than the tiny, privately-owned holdings had done. 30–40 million tons of grain was produced every year. Collectivisation also meant the introduction of mechanisation into the countryside where, previously, the peasants had never seen a tractor. Now, two million previously-backward peasants learned to drive a tractor. New methods of farming were taught by 110,000 engineering and agricultural experts. The countryside was indeed transformed." - Elizabeth Roberts, Stalin: Man of Steel (1968)

Collectivisation as a catastrophe

Others argue it was economically inefficient, socially devastating, and caused unnecessary famine and death

They see collectivisation as a reckless exercise in state control rather than rational economic policy

Key historians

"It was a complete disaster from which, it is probably no exaggeration to claim. Russia has not fully recovered even today. There was no problem in collectivising landless labourers, but all peasants who owned any property at all, whether they were kulaks or not, were hostile and had to be forced to join by armies of party members who urged poorer peasants to seize cattle and machinery from the kulaks to be handed over to the collectives. Kulaks often reacted by slaughtering cattle and burning crops rather than allow the state to take them. Peasants who refused to join collective farms were arrested and deported to labour camps or shot; when newly collectivised peasants tried to sabotage the system by producing only enough for their own needs, local officials insisted on seizing the required quotas, resulting in large-scale famine during 1932-3, especially in the Ukraine. Yet one and three-quarter million tons of grain were exported during that period while over five million peasants died of starvation. Some historians have even claimed that Stalin welcomed the famine, since, along with the 10 million kulaks who were removed or executed, it helped to break peasant resistance." - Norman Lowe, Mastering Modern World History (1988)

"The war against the 'kulaks' was not a side-effect but the main driving force of the collectivization campaign. It had two main aims: to remove potential opposition to collectivization; and to serve as an example to the other villagers, encouraging them to join the collective farms in order not to suffer the same fate. As Stalin saw it, there was nothing to be gained from trying to neutralize the 'kulaks', nor from attempting to involve them as farm labourers in the kolkhoz, as some Bolsheviks proposed. 'When the head is cut off,' Stalin argued, 'you do not weep about the hair.' In January 1930, a Politburo commission drew up a target of 60,000 'malicious kulaks' to be sent to labour camps and 150,000 other 'kulak' households to be exiled to the North, Siberia, the Urals and Kazakhstan. The figures were part of an overall plan for 1 million 'kulak' households (about 6 million people) to be dispossessed and sent to labour camps or 'special settlements.'" - Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy (1996)

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?