The Status of Soviet Women in the Towns (Edexcel A Level History): Revision Note

Exam code: 9HI0

Summary

From 1917–1985, Soviet leaders promised gender equality to the urban woman

However, women rarely achieved it

Women’s roles shifted with each phase of Soviet history

Some eras saw the revolutionary emancipation of women and acknowledged their wartime heroism

Other periods saw stagnation, and women were forced to take up traditional gender roles

Employment and education expanded dramatically, yet women continued to face a “double burden” of work and family

Historians disagree whether the USSR truly liberated women or simply used them as tools of ideology and labour

Soviet attitudes toward women in 1917

Marxism and sexual equality

Marxist theory viewed women’s oppression as part of capitalist exploitation

Equality was central to the revolution

Women were to be “workers first, mothers second”

Lenin and Marxist views towards women

Lenin saw women’s emancipation as essential for socialism:

“No social revolution can be successful without the participation of women.”

Lenin and Bolshevik leaders argued that women could only be liberated through:

Economic independence

Collective social structures, such as communal childcare and kitchens

Early Social Reforms

Bolshevik decrees gave women new rights:

Divorce is made available at the request of either partner

Abortion was legalised in 1920

The USSR was the first country in the world to do so

Equal pay and legal equality were established in law

Maternity leave and workplace protections were introduced

Appointed Alexandra Kollontai as Commissar for Social Welfare

Kollontai was the first woman in government in modern Europe

The impact of the Russian Civil War on women

Propaganda and gender roles

Civil War propaganda focused on women as mothers, nurses, and wives — not revolutionaries.

Imagery reinforced women’s role in supporting male soldiers rather than fighting themselves.

The state’s need for stability meant domesticity replaced emancipation.

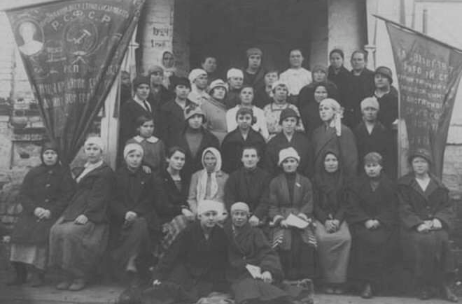

The role of the Zhenotdel

The Zhenotdel was a women's department in the Communist Party

Founded in 1919 by Alexandra Kollontai and Inessa Armand to promote women’s rights

Organised the following for working women:

Literacy campaigns

Childcare centres

Training programmes

Aimed to make Party policy accessible to women in towns and factories

Women during the NEP

End of War Communism led to mass unemployment

Many women lost industrial jobs

A large rise in female unemployment, especially among urban workers

Prostitution increased due to poverty and lack of welfare support

Women’s economic independence declined sharply

The impact of industrialisation on women in towns

The 1930s and Stalin’s Five-Year Plans

Massive industrial expansion required new labour

Millions of women joined the workforce

Women made up:

29% of the industrial workforce in 1929

43% by 1940

Propaganda portrayed women as heroic workers

The “Stakhanovite Woman”

Female tractor drivers

Crèches and canteens improved urban childcare

Despite this:

Women rarely reached managerial positions

There was no equal pay

Women earnt on average 40% less than men

Workplace conditions were often unsafe

Women in the Second World War

Women filled roles left by conscripted men

3 million women entered the workforce

Thousands served as nurses, mechanics, and even snipers and pilots (e.g. the “Night Witches”)

Despite wartime heroism, women were expected to return to domestic roles after 1945

Post-war restrictions

After 1945, many industries were reclassified as ‘male-only’

This excluded women from heavy work

State focus shifted back to family and motherhood, promoted through propaganda

The birth rate was seen as a measure of national strength

Between 1936 and 1955, abortion was banned

Female employment in the Brezhnev era

Industrialisation continued, and women remained vital to the workforce:

By 1985, 90% of working-age women were employed in towns or state enterprises

However, they were concentrated in low-paid sectors like:

Education

Health

Clerical work

The BAM campaign

The BAM (Baikal–Amur Mainline) campaign recruited women to remote regions to boost labour supply

Propaganda called them “the BAM brides”

Wages and promotion opportunities remained limited

Few women reached managerial roles

Examiner Tips and Tricks

Always specify when you are referring to urban women, especially when comparing to the lives of collectivised peasants.

Urban women had far more opportunities than rural women.

Women in politics in the USSR

Party membership and representation

1917-1953

Despite early rhetoric, female political participation remained low

In the 1920s, women made up only 12% of Party membership

In the 1930s, many withdrew due to traditional expectations of family duties

By 1953, women held only 20% of local soviet seats and were almost absent from top-level positions

1953–1980s

Khrushchev and Brezhnev both promoted female representation in local soviets, but this was mainly symbolic.

By the 1980s:

Women were 33% of Party members but held very few leadership roles

Most female officials worked in education, welfare, or health committees — the “soft” sectors

Political culture remained male-dominated, with women valued more as workers and mothers than as policymakers

What was the status of women in the USSR by 1985?

Historians debate whether the USSR truly emancipated women, or continue to treat them less than men

The Soviet state improved women's status

Women achieved mass participation in work and education

Legal equality existed

Women could vote, work, and access education

Urban living standards improved

Healthcare, maternity benefits, and childcare were expanded

Key historians

"Estimates made in the mid 1960’s of female enrollments in various disciplines of higher educational institutions show that 53 percent of the medical students, 75 percent to 80 percent of the biology students, 25 percent of the students in agronomy, about two-thirds of the chemistry students, almost half of the students in mathematics, and from 25 percent to 40 percent of those in the physical and geological sciences were women. These figures are strikingly high when compared with other countries. The result is an extraordinary large number of female scientists and technicians. According to Dodge, 63 percent of all specialists with specialized secondary education, 92 percent of the semi-professional medical personnel, and 75 percent of the planners, statisticians, and accountants were women. In fact more than half of the mental workers in Soviet Russia are women. And this is in a country where, two decades before the Revolution, a bewildered peasant could ask a woman pharmacist “Can it really be so, young lady, that a woman’s mind can fathom such matters?”" - Richard Stites, The Women's Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860-1930 (1977)

"After all, this was a decade in which millions of women were entering the workforce and being encouraged to do so. The regime was doing its best to increase the number of women in higher education and the professions and, with less success, to promote women to administrative positions. Women in the Soviet Union were brought up to think they should have careers: as a Harvard Project respondent reported, “at meetings and lectures they constantly told us that women must be fully equal with men, that women can be flyers and naval engineers and anything that men can be”... By 1939, in any case, the earlier homemaking emphasis of the wives’ movement was giving way to a focus on women learning to do men’s work and entering the workforce. This was both an internal development within the movement and a response to the imminence of war and the likelihood that men would soon be conscripted" - Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s (1999)

The Soviet state did not improve women's status

Persistent wage inequality and limited career progression

Women faced the 'double burden'

The state expected women to work full-time and carry out all of the household duties

The state praised women as mothers, not leaders

This went against Marxist ideals

Key historians

"The 'new Soviet person' came, of course, in a male and female form. However, the 'new woman' presented more of a problem than the 'new man'. It was acknowledged that working-class women had suffered oppression on account of gender as well as class, and that this had left them with a lack of confidence and a greater degree of political backwardness than men... The revolutionaries were agreed that women had to be freed from domestic servitude and drawn into social production. This would ensure, as Lenin put it, that they enjoyed the exact same position as men. However, women clearly had a duty which men could not perform. As well as being workers themselves, they also had to produce the next generation of workers. They had to be some kind of balance in their lives between production and reproduction, between work and family. Getting this balance right did not prove easy, especially against the background of shifting economic and demographic priorities. Accordingly, periodic adjustments were made to the image of the new woman." - Lynne Attwood, Creating the New Soviet Woman: Women's Magazines as Engineers of Female Identity, 1922-53 (1999)

"Women were spending three times longer than their men on household chores, but by 1936 they were spending five times longer. For women nothing changed—they worked long hours at a factory and then did a second shift at home, cooking, cleaning, caring for the children, on average for five hours every night—whereas men were liberated from most of their traditional duties in the home (chopping wood, carrying water, preparing the stove) by the provision of running water, gas and electricity, leaving them more time for cultural pursuits and politics." - Orlando Figes, Revolutionary Russia, 1891-1991 (2014)

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?