Weather hazards (WJEC Eduqas GCSE Geography B): Revision Note

Exam code: C112

Specification links

The notes on this page cover part 2.3.3 of the WJEC Eduqas B specification.

2.3.3 - How are weather hazards distributed at a global scale and how does this pattern change over time?

How global circulation creates areas of high and low pressure.

The distribution and location of these pressure systems should be discussed.

Typical weather patterns and the extreme weather hazards associated with high- and low-pressure systems should be discussed.

Coverage should include:

The use of weather charts.

Temporal and spatial changes in extreme weather to include

Seasonal and longer-term changes in the tropics which result in drought (note the link to changing patterns of desertification in 3.4.1)

The seasonal distribution of cyclones/hurricanes.

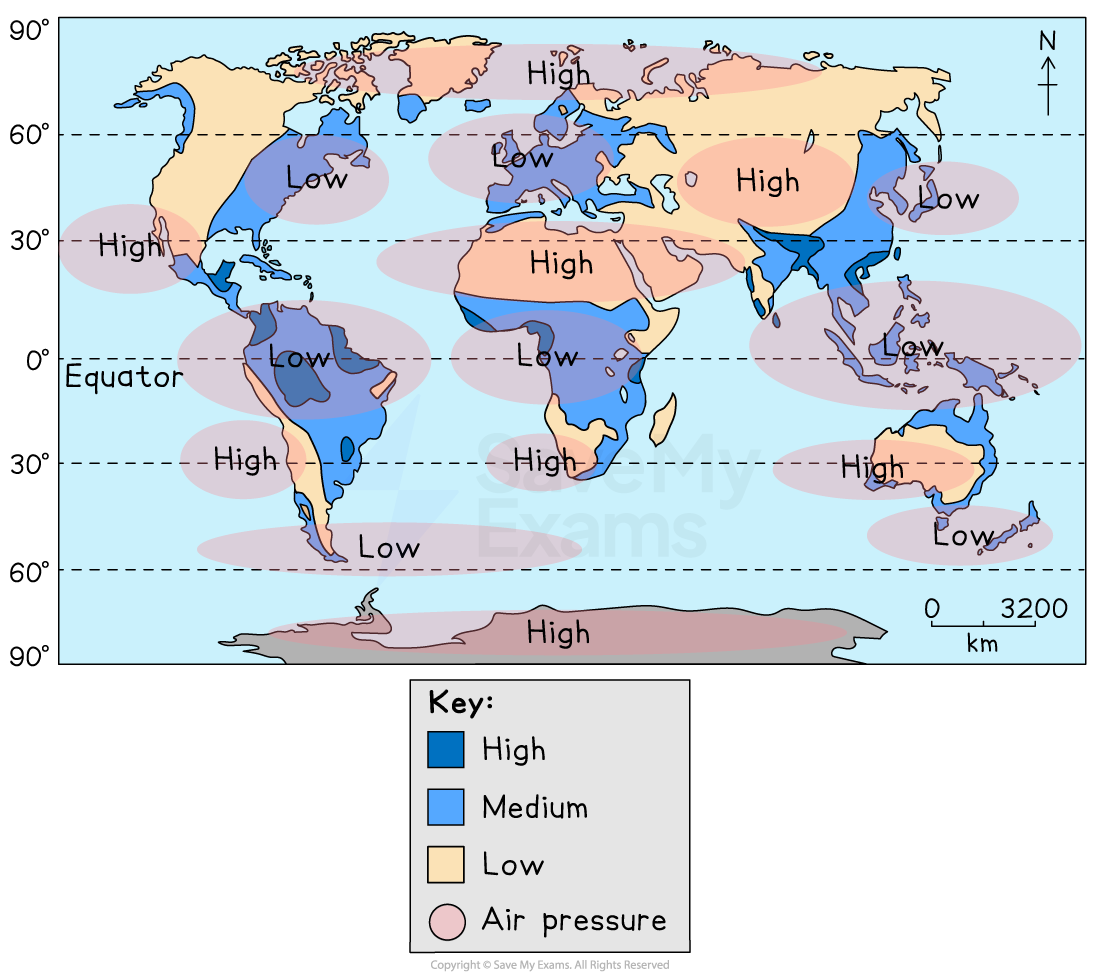

Global circulation – high and low pressure

Wind formation

To circulate the warm air around the Earth, specific wind and pressure patterns exist

Air always moves from high pressure to lower pressure

This movement of air generates wind

Pressure differences occur because the Earth's surface is heated unevenly

It starts at the equator, which is the hottest part of the Earth

Air rises at the equator, leading to low pressure and rainfall at the surface

Once the rising air hits the edge of the atmosphere, it travels north and south

As the air becomes cold, it begins to sink, creating high pressure and dry air as it descends

The cool air will 'rush' from the high-pressure zone to the low-pressure zone at the equator to be warmed again by the Sun, at the same time creating wind

Pressure differences

Air moves in the atmosphere either towards the ground (subsidence) or up into the atmosphere (convection)

These movements influence air pressure and rainfall

The sea and land heat up differently

Sea:

Forms high pressure in summer and low pressure in winter

It takes longer to heat and cool

Air is denser and cooler in summer but warmer in winter

Land:

Generally, it forms areas of lower pressure in summer and higher pressure in winter

It heats quickly in summer and the air is lighter and rises

It cools quickly in winter

The influence of air movement on weather conditions

Subsidence (sinking air)

This occurs in areas with lower levels of solar radiation, such as the mid-latitudes, the poles or at high altitudes where the air is very cold

Air becomes denser and sinks towards the ground, forming high-pressure areas

As air sinks, it begins to warm and can hold more moisture, preventing clouds from forming

High pressure brings clear skies or very thin clouds

It creates arid or semi-arid conditions due to very little precipitation.

Convection (rising air)

This occurs in areas with higher levels of solar radiation, such as the equator

The ground heats the air above and rises, where it begins to cool and condense into water droplets, which form clouds

Low-pressure areas are created as air moves upward

Thick, heavy cloud cover with heavy rainfall creates wet tropical regions

Global pressure belts

The horizontal bands of the Hadley, Ferrel, and Polar cells create a large pattern of high- and low-pressure belts around the Earth

The pattern is not the same in each hemisphere, even though the cells are mirrored

This is because the location of these pressure zones is affected by the amount of land and sea

There is more land in the northern hemisphere and more sea in the southern hemisphere

Coriolis effect

Winds are influenced by the Coriolis effect

The Coriolis effect is the appearance that global winds and ocean currents curve as they move

The combination of pressure cells, the Coriolis effect, and the three cells produces wind belts in each hemisphere

The trade winds blow from the subtropical high-pressure belts (30 ° N and S) towards the Equator's low-pressure zones and are deflected by the Coriolis force

The westerlies blow from the sub-tropical high-pressure belts to the mid-latitude low areas but, again, are deflected by the Coriolis force

The easterlies: Polar easterlies meet the westerlies at 60° S

Weather patterns and extreme weather

Global atmospheric circulation affects the Earth's weather patterns

It causes either a depression or an anticyclone

The UK has a lot of low-pressure weather systems (depressions) that are blown in from the Atlantic Ocean on south-westerly winds, bringing wet and windy weather

These pressure systems bring extreme weather events to many regions of the world and include:

storms/gales

heavy rain

thick fog

heatwave

heavy snowfall

drought

cyclones/hurricanes

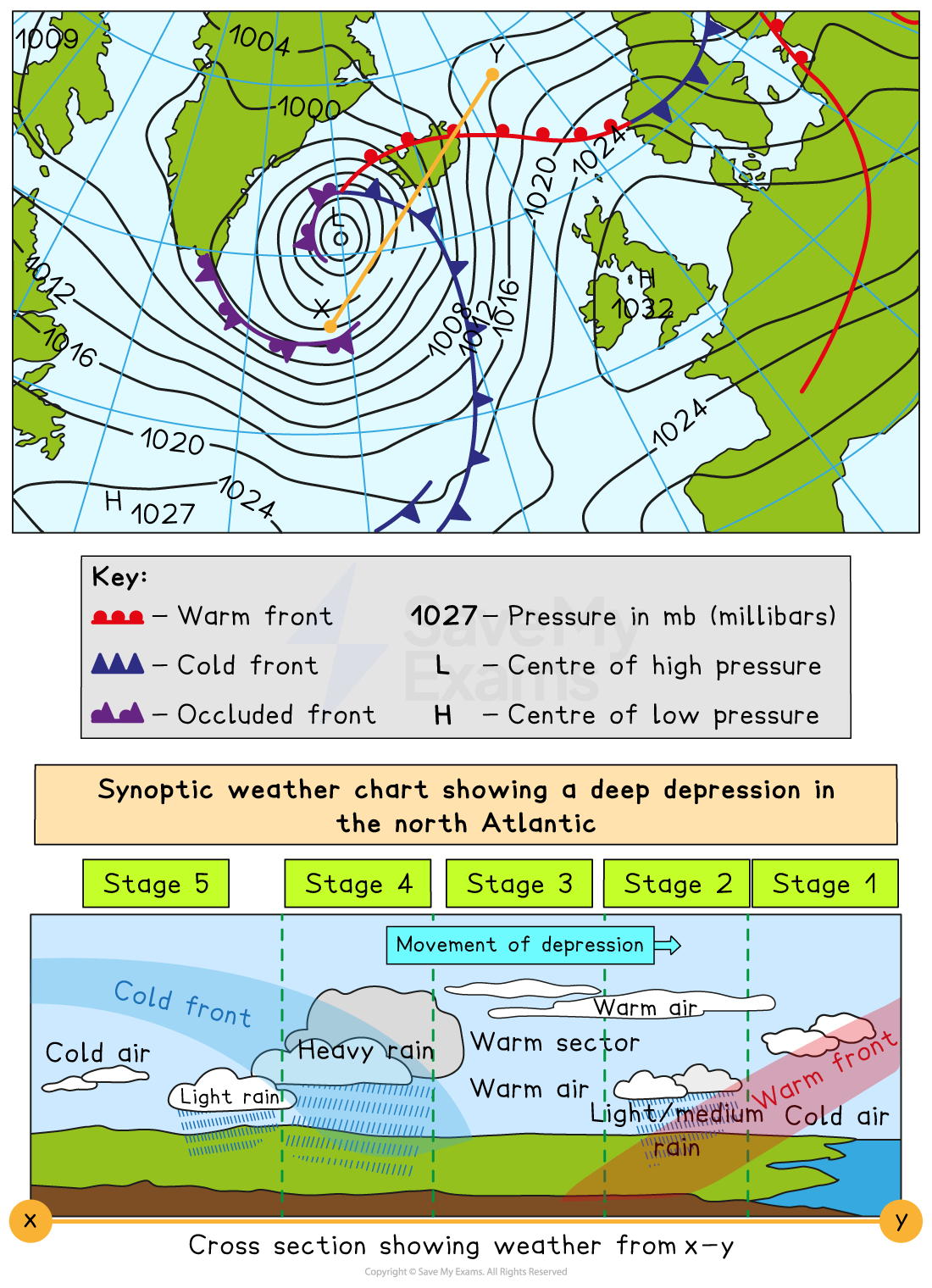

Weather fronts

Weather fronts form when different masses of air with varying temperatures and amounts of moisture meet

Fronts are the boundaries between air masses

The area behind the front is known as a 'sector'

Weather fronts are shown on charts using lines and symbols and they point in the direction the front is moving in:

Cold fronts are shown by blue lines with triangles as a steep, rounded face

Cold air is advancing and pushing underneath warmer air

The tips of the triangles indicate the direction of movement of the cold air

Warm fronts are shown by red lines with semicircles as a gradually sloping face

Warm air is advancing and rising up over cold air

The edges of the semicircles indicate the direction of movement of the warm air

Occluded fronts are shown by purple lines with alternating triangles and semicircles

A cold front 'catches up' with a warm front

The cold front lifts the warm air up from the surface, which is then ‘hidden’

An occlusion has the characteristics of both warm and cold fronts

The amount of rain depends on the strength of a front and the temperature difference between the air masses that they separate

As a warm front moves past, a sector of warm air follows behind it, making the temperature rise

The temperature drops when a cold front goes by, as it brings colder air with it

Depression

A depression is an area of low atmospheric pressure (<1004 mb). It is usually characterised by:

Winds spiral towards the centre and are strongest along the cold front

Isobars are close together

It is wettest along the cold front

The lowest rainfall occurs in the warm sector

The temperature is typically warmer in the warm sector behind the warm front and cooler in the cold sector behind the cold front

As a depression travels, the following occur:

Before the warm front arrives

Cloud cover: Increases to thicker, lower clouds

Pressure: Is relatively high before it starts to fall steadily

Temperature: Remains cool or mild

At the warm front

Cloud cover: Continues to thicken

Precipitation: Steady, continuous rain or drizzle begins

Temperature: Starts to rise as the warm air mass moves in

Between the warm and cold fronts

Cloud cover: Scattered or clear with dry weather

Pressure: Reaches its lowest point before beginning to rise again

Temperature: Remains warm

At the cold front

Cloud cover: Develops into tall, heavy clouds

Precipitation: Heavy rain showers and thunderstorms occur as the cold air forces the warm air to rise rapidly

Temperature: Drops noticeably

After the cold front passes

Cloud cover: Breaks up

Pressure: Continues to rise

Temperature: Remains cool

Anticyclone

An anticyclone is an area of high atmospheric pressure (>1008 mb) where air is sinking

As the air sinks, no clouds or rain are formed

The air gets warmer as it sinks, so it can hold more water

Winds spiral outwards from the centre and are usually light with settled, dry and bright conditions

Isobars are far apart

In the summer, anticyclones bring dry, hot weather

In the winter, clear skies bring cold nights and frost

In cold weather, anticyclones can bring fog and mist because the cold causes air moisture to condense at low altitudes

Examiner Tips and Tricks

Wind spirals in different directions depending on which hemisphere it is in and if it is a high- or low-pressure system.

Northern hemisphere

Anticyclone - clockwise

Depression - anticlockwise

Southern hemisphere

Anticyclone - anticlockwise

Depression - clockwise

Weather (synoptic) charts

Meteorological readings are plotted on weather charts

They can show some or all of the following:

wind speed

wind direction

pressure patterns with isobars

weather fronts

cloud cover

temperatures

Simple weather chart Anticyclones (high-pressure systems) can be identified on a synoptic chart due to:

Widely spaced isobars

No fronts/clouds

Isobars show pressure increasing (above 1008mb) outwards from the centre

Depressions (low-pressure systems) can be identified on a synoptic chart due to:

Closely spaced isobars

Fronts/clouds

Isobars show pressure decreasing (below 1004mb) towards the centre

Worked Example

Identify the correct answer in each box.

[4 marks]

Features of a typical depression | Identify the correct answer |

|---|---|

Where are the winds strongest? | warm front / warm sector / cold front |

Where is the air warmest? | warm front / warm sector / cold front |

Where does the heaviest rain occur? | warm front / warm sector / cold front |

Where is rainfall the lowest? | warm front / warm sector / cold front |

Answer

The winds are strongest at the cold front. [1 mark]

The air is warmest in the warm sector. [1 mark]

The heaviest rain occurs on the cold front. [1 mark]

The lowest rainfall is in the warm sector. [1 mark]

Temporal and spatial changes in extreme weather

Extreme weather is changing over time and space

Many events are happening more often and with more force

There is a trend towards heavier rain, hotter heatwaves, and longer dry spells around the world

However, the effects are different depending on location and the time of year

For example, depending on latitude and longitude, some places have wetter winters and drier summers, while others are seeing damaging winds and heavy flooding

Temporal changes (changes over time)

Studies show there is an increased frequency and intensity of high- and low-pressure systems bringing heavy rain and flooding or heatwaves over time

In some places, the number of dry days in a row has decreased, but the length of the dry spell has been increasing, resulting in droughts

Overall rainfall totals do not show a clear change, but some places are seeing wetter winters and drier summers

Spatial changes (changes across locations)

Latitude influences the type and severity of extreme weather events in a given area

For example, people living nearer to the Equator often suffer from life-threatening conditions such as tropical cyclones and droughts

Tropical cyclones:

Hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones form between 5° and 30° latitude north and south of the equator, where warm ocean water (above 27°C) provides the necessary energy

Tropical storms are rotating, intense low-pressure systems (below 950mb)

They are known as:

Typhoons in the South China Sea and the western Pacific Ocean

Hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea and the west coast of Mexico

Cyclones in the Bay of Bengal, the Indian Ocean and northern Australia

While the total number of storms may not increase, warmer sea surface temperatures are intensifying them, leading to more powerful and damaging events

Cyclones are seasonal events that occur between June and October in the northern hemisphere and December and March in the southern hemisphere

Temperature extremes:

Polar regions experience lower-angle solar energy, resulting in colder climates and extreme cold weather events

However, tropical and subtropical zones are prone to more frequent and intense heatwaves, especially in mid-latitude and semi-arid regions

This is due in part to a band of low pressure in the atmosphere known as the tropical rain belt

This belt is where the two hemispheres' trade winds meet and is called the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)

Warm, moist air has to rise at the Equator because of this meeting, which causes heavy rain, thunderstorms, and the formation of cloud bands

The ITCZ moves with the seasons because it follows the area of highest solar heating, making tropical areas have distinct wet and dry seasons

Monsoons

In mid-latitude regions, temperatures change over a seasonal cycle, and weather events last just a few days

This might make it cool and rainy one day and warm and sunny the next

However, in tropical latitudes, temperatures don’t change much throughout the year

The tropical season is a shift between dry and wet periods brought about by monsoons

A monsoon is not a storm but a large pattern of winds and rain that covers a geographic area like a continent

The summer monsoon has large amounts of rain

The winter monsoon has dry conditions

During the winter, air descends, causing high pressure

The dry conditions during winter can even lead to drought if they are too intense or too long

Climate change and tropical storms

Global temperatures are set to rise as a result of global warming

More of the world's oceans will be above 27° C; therefore, more places across the world will experience tropical storms

Oceans will stay at 27°C or higher for longer during the year, which will increase the annual number of tropical storms

Higher temperatures will mean storms will be stronger and more frequent and cause more damage

Worked Example

Suggest one way the distribution of tropical storms could change if global ocean temperatures continue to rise.

[1 mark]

Answer

They may affect areas further from the Equator. [1 mark]

They could affect parts of the sub-tropics/the South Atlantic/NE USA. [1 mark]

They could have a broader distribution/effect on larger parts of the world. [1 mark]

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?