Write about Ruth in Never Let Me Go and how Ishiguro presents her importance to the novel as a whole.

In your response you should:

refer to the extract and the novel as a whole

show your understanding of characters and events in the novel.

5 of this question’s marks are allocated for accuracy in spelling, punctuation and the use of vocabulary and sentence structures.

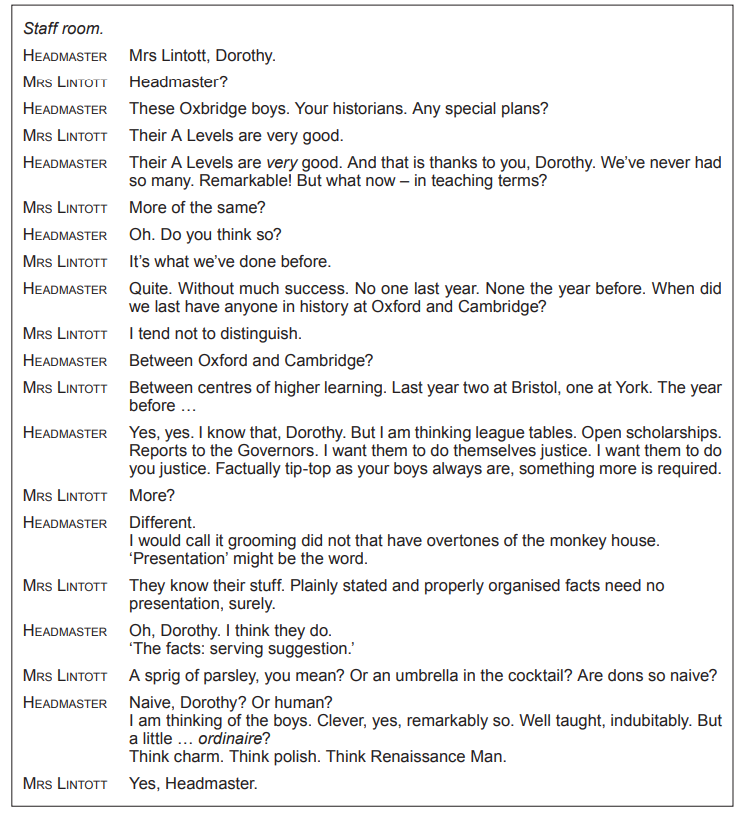

We stopped again further down the street, talking excitedly all at once. Except for Ruth, that is, who remained silent in the middle of it. It was hard to read her face at that moment: she certainly wasn’t disappointed, but then she wasn’t elated either. She had on a half-smile, the sort a mother might have in an ordinary family, weighing things up while the children jumped and screamed around her asking her to say, yes, they could do whatever. So there we were, all coming out with our views, and I was glad I could say honestly, along with the others, that the woman we’d seen was by no means out of the question. The truth was, we were all relieved: without quite realising it, we’d been bracing ourselves for a let-down. But now we could go back to the Cottages, Ruth could take encouragement from what she’d seen, and the rest of us could back her up. And the office life the woman appeared to be leading was about as close as you could hope to the one Ruth had often described for herself. Regardless of what had been going on between us that day, deep down, none of us wanted Ruth to return home despondent, and at that moment we thought we were safe. And so we would have been, I’m pretty sure, had we put an end to the matter at that point. But then Ruth said: ‘Let’s sit over there, over on that wall. Just for a few minutes. Once they’ve forgotten about us, we can go and have another look. ’ We agreed to this, but as we walked towards the low wall around the small car park Ruth had indicated, Chrissie said, perhaps a little too eagerly: ‘But even if we don’t get to see her again, we’re all agreed she’s a possible. And it’s a lovely office. It really is.’ ‘Let’s just wait a few minutes,’ Ruth said. ‘Then we’ll go back.’ |

Was this exam question helpful?