Pigeon English: Themes (AQA GCSE English Literature): Revision Note

Exam code: 8702

Pigeon English: Themes

In your GCSE English Literature exam, the essay questions on Stephen Kelman's Pigeon English may ask you to consider any of the themes of the novel (or its central ideas). You will also need to demonstrate that you understand how the writer presents these ideas, and why they may have been presented this way.

Here are some of the key themes in Pigeon English to revise:

Inequality, discrimination and societal pressures

Immigration and identity

Loss of innocence

Masculinity and violence

Death

Inequality, discrimination and societal pressures

Harri lives in a multicultural city and a very multicultural community. We see the ways that poverty and crime strike this area, but also how contrasting ideas and values — about race, nationality and belonging — impact its residents.

Inequality

Knowledge and understanding

We regularly see how the community has limited access to nature, and the degradation of the local environment:

The “baby trees are in a cage”, which Harri thinks are to stop them being stolen

Much like the community, this natural object is caged, in a way that would be said to be for its protection

The personification of these trees shows how residents of this area are oppressed

Kelman draws a link between the corruption of the area and the abuse of the natural environment

Kelman also shows the reader many images of poverty:

Harri tells us that all he can see from his balcony is the car park and the bins

Rather than nature, colour and joy, Harri is given an ugly, stark and lifeless view

We then hear how “every time somebody shuts their door too hard my flat shakes”, which tells us how Harri lives in a cheap, poorly made apartment building

Poverty is why Mamma has to work day and night, which leads to the children being left without her guidance as Miquita’s influence grows:

Had Mamma been home, Lydia would have spent less time with Miquita and not gotten involved with disposing of the dead boy’s coat

Later, Harri would have been safe from Miquita molesting him

We even see how the environment begins to put pressure on Harri and Lydia’s relationship:

She “never used to shut the door in my face” back home:

There is symbolism here, how doors are opening and closing for different people and on different opportunities

Crime and illegality

Knowledge and understanding

The poverty we see in the area reduces local services, giving children less to do and making crime a key part of all lives

The CCTV cameras that are seen everywhere show that the community is constantly monitored:

This suggests not only that crime is rampant, but established as something they all do, so they are all under watch:

Harri says that, “the devil must be mighty strong around here, there’s cameras all over the place!”

All the boys are aware of crime and violence:

They practise “chooking” (stabbing) at school

Drugs are also commonplace:

The boys are exposed to a crack spoon and play dares around it, all knowing what it is and not at all surprised by it

Dean and Harri make a base during their investigation, which is safe because “only the junkies use” the area

Harri and Dean both dislike the Dell Farm Crew, but both imitate them:

Harri’s desire to join them shows how a sweet boy from Ghana can be enticed by power

In an environment where there is often chaos and unpredictability, the easiest route to control is power, and the easiest route to power is through bad deeds:

We see this with the initiation tasks as a direct route into the Dell Farm Crew, but also in acts like Harri pushing over the younger boy who enjoyed the tree being cut down, or charging the younger kids to use the mattress:

This is a direct contrast to Harri’s life back home, where he has memories of making a roof for his Papa’s shop, and says he felt “strong because you made it yourself”

London was still the goal for Harri’s family, still a prize, and one they got to using illegal methods:

Mamma tells Auntie Sonia that without Julius’ help, she would have still been home “putting my coins in a Milo tin”:

Their own poverty means they could not afford the whole family coming over, and that they had to use illegal routes to reach the UK

There is also the parallel of the two dogs in the story:

X-Fire’s dog, Harvey, is violent, aggressive and terrifies people

Conversely, Terry’s dog Asbo is a placid and pleasant dog:

This contrast shows us that the labels we give people (and animals) do not confirm their nature

An ASBO is an Anti-Social Behaviour Order, a common legal discipline tactic at the time

It also shows how nurture trumps nature; Terry is a nicer man, so his dog is much friendlier

Racism

Knowledge and understanding

Harri and his family endure racism in different ways:

When playing football, Vilis won’t pass the ball to Harri because he is Black

At work, Harri’s Mum is racially abused, and we see how Mamma and Auntie Sonia shield Harri from it by explaining away the comments he doesn’t understand

When discussing Sonia’s burnt fingers, Harri talks about how it is harder to travel when you are Black, especially for migration, believing that “some of the countries won’t let you in if you’re black”

These stories emphasise that racism and xenophobia mean that people have unequal access to home and the feeling of belonging

The novel also delves into how multicultural communities are not harmonious just because they are grouped together:

Harri perpetuates negative stereotypes, absorbing them from his surroundings:

He befriends a Somali boy, Altaf, even though he explains “you’re not supposed to talk to Somalis because they’re pirates”

He sees a Muslim girl praying, and finding her peaceful, believes her prayer “couldn’t be bombs” and that it “had to be something good”

Even though we see Harri’s good nature squash these prejudices, he has clearly internalised them

Harri feels bad for Dean having his money taken and acknowledges it’s because Dean is white:

However, Harri admires the power of it

What is Kelman’s intention?

Kelman uses the behaviour of children to highlight how the environment we grow up in influences who we are:

The children in Pigeon English are all products of their environment

Much of the racism in the novel is spread by the children, all of which is learned behaviour

The author shows that common natural things (plants and trees, for example) or a clean and pleasant environment are not seen as a necessity for these people:

This mirrors how governments take away services and benefits to citizens of lower socio-economic status

Kelman draws parallels between attacks on the natural environment and the behaviour around it, with Harri pushing over a child in anger when he appears to be enjoying the tree coming down

Kelman consistently shows his audience that opportunity, hope and beauty is limited for people who need it most

Immigration and identity

Home is a shifting concept throughout Pigeon English. Harri and his family are framed as having recently arrived in London, still within the first few months of their move from Ghana. Their family is split apart, their new home and their old home not just a long way from each other in distance, but in terms of culture and comfort, and Harri and Lydia are struggling with finding their place. In a different location, with family split, and a weak sense of security, home is hard to find.

Knowledge and understanding

The title of the book is a play on the term “pidgin English”:

Pidgin English is a dialect of English, often used by people of different languages who have learned English, creating a hybrid dialect

Harri mixes British English with pidgin English and Ghanaian slang

We get words and phrases like “hutious” (scary), “Adjei” (a Ghanaian surname), and “dey touch” (over-familiar) throughout:

Readers unfamiliar with the words’ meanings will have learned what the words mean from context by the end of the novel

This is similar to Harri’s journey, as he is constantly learning new words, phrases and social rules as he goes

Harri learns about his new home more from the people around him than through school, becoming part of the cycle of social inequality

Harri struggles to settle in London:

He is promised that his family is coming, and that they will be “home” when they are together, although there are never any concrete plans presented at any point during the novel

When Harri laments that there are “no songs in my new school”, it gives us the contrast of silent, joyless school halls and the idea of loud and vibrant songs of his home in Ghana:

Signing is a communal activity, highlighting the community that Harri has lost

This is the same at the funeral:

Harri notes that there is no singing, and that funerals in the UK are solemn and cold, compared to the celebrations of life back home

Lydia struggles to find comfort, too, and presents differently to new friends compared to with her brother:

She acts tough when Miquita is around, but shows her younger, freer side when alone with family

As bonds break with Miquita, she looks to protect her younger brother

She cries when receiving the package from home, missing her father and her family unit being whole

The differences between London and Ghana are shown often:

Harri’s naivety to this new world can be seen in his confusion over the playground sign that says, “Say No to Strangers”

When Mr Frimpong is mugged by the Dell Farm Crew, he is disappointed to find that strangers do not look out for each other here

In contrast, Harri tells stories about helping in his local community in Ghana, and the idea that to help strangers is encouraged and expected

Harri’s desire to connect with others ends up causing him troubles:

The dead boy was a relative stranger — Harri barely knew him at all — yet relating to him and feeling he can save him sees him suffer consequences

The characters of Auntie Sonia, Julius and Mamma tell a different immigrant story:

The illegal visas that Julius sells allowed the family into England

Sonia is presented as a figure without a home, who moves often

She burns off her fingerprints so that she cannot be tracked and detained by immigration authorities as, in Harri’s words, “they don’t know where you belong so they can’t send you back”

This also suggests that Sonia has nowhere to belong now:

This is one reason she anchors herself in an abusive relationship, because at least she has a roof over her head and a place to live, even if Julius mistreats her

We see the lack of security in the life of illegal immigrants as Pakistani couple Nish and his wife are arrested by police and face deportation

At the end of the novel, the pigeon assures Harri he is going home:

Harri is never truly home in the story, and now is again moving on to a new home

The story presents us with the idea that home is a myth, something we are always chasing, and is out of reach

When the pigeon tells Harri, “you’ve been called home” and that he is “going home soon”, Harri believes this to mean heaven, which prompts him to ask whether the pigeon is working for God

With no answer, we are left unsure whether Harri is going to heaven, his Christian home, or if it means something else

In the end, Harri is leaving two homes, unable to get what he wants from either before the story ends for him

What is Kelman’s intention?

Kelman forces the reader to examine the hostile environment created for immigrants in the UK, and the constant challenges they face.

Harri’s innocent thoughts on differences are contrasted with the harsh realities that his Mamma and Auntie Sonia are battling

By placing their issues in the background of the story, it shows how they are hidden from children, but also hidden from us

Kelman also shows how, even with the different specifics, we are all people, and we all experience personal battles to survive

The story also challenges us to face how we dehumanise immigrants to enable us to ignore their plight

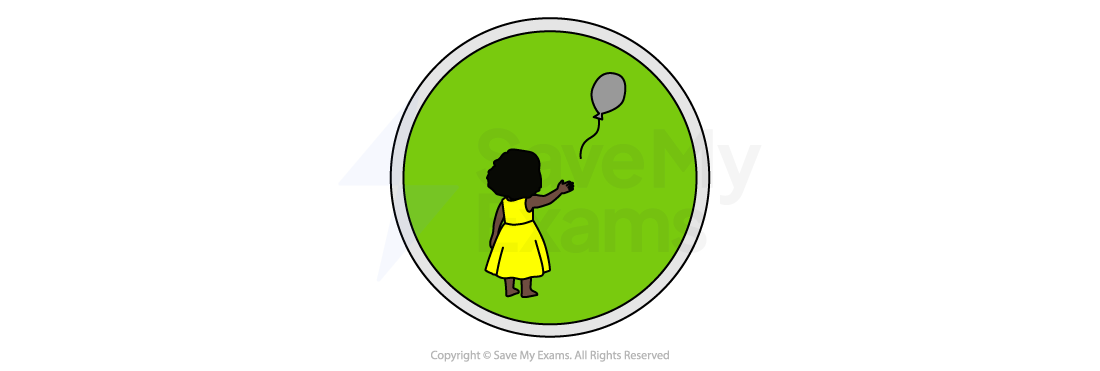

Loss of innocence

There are different ways we see characters lose their innocence throughout Pigeon English. The children are all in a period of life where they are coming of age, and the novel shows us typical teenage experiences alongside how the challenges of their community strip innocence from children.

Knowledge and understanding

In the beginning, Harri quickly starts to compare his school jumper to the dead boy’s, stating that “my uniform’s better”:

This very immature reaction shows both that he is egocentric, as young children are

It also reflects a lack of innocence, in that he can quickly forget the blood because it isn’t shocking

The sentences are also short, highlighting a childish vocabulary (“His jumper was green. My jumper’s blue. My uniform’s better”)

By the end of the novel, Harri’s reaction to his own death and blood reveals he has matured:

At the start of the novel, he is egocentric

By the end, Harri is content to know his baby sister will learn his story and grow older

Harri is constantly learning from the new experiences of his life in London:

He dislikes the Dell Farm Crew, but also wants to join them to escape bullying and to be more popular

It takes for the mugging of Mr Frimpong for Harri to realise the gang are not people he wants to be aligned with

We see a contrast in his relationship with Poppy Morgan and the sexual advances of Miquita:

Harri’s use of language betrays his naivety, for example misinterpreting what “orgasm” means

Much like how the mugging of Mr Frimpong strips Harri of his naive notions of the gang, when Miquita molests him, she steals a part of his innocence

In comparison, Poppy giving him a kiss on the cheek is one of the most exciting moments of his life

We also have contrasts in Harri’s friendships:

The likes of Dean and Connor are more innocent friends, playing games, drawing, teasing, wanting to be the fastest or strongest, telling juvenile lies

Then there is Jordan, and the Dell Farm Crew:

Jordan always pushes Harri to do things out of his comfort zone

The Dell Farm Crew twice push Harri to do things that he cannot, due to guilt

Lydia is also a victim of peer pressure. We see this in her friendships with Miquita and Chanelle:

Lydia is most excited for the dance club

She ends up being taken advantage of by Miquita, who makes her destroy evidence and then burns her as a threat

After this, her guilt emerges, and she destroys her dance outfit, the joy of it ruined by Miquita’s actions

After naively going into a friendship with pure intentions, Lydia now feels trapped

What is Kelman’s intention?

Kelman shows us how the children in his novel are robbed of their innocence by the environment they are in

It is made clear throughout that none of the young characters is able to have a typical childhood, directly contrasting the childhoods of most of his audience:

This is an attempt to shock readers into facing the reality these children face

Kelman writes about common coming-of-age issues, reminding us that teenage and pre-teen children are trying to face common difficulties, too:

This helps the audience relate to their own youth, and helps to ground the more extreme behaviour and actions in the novel

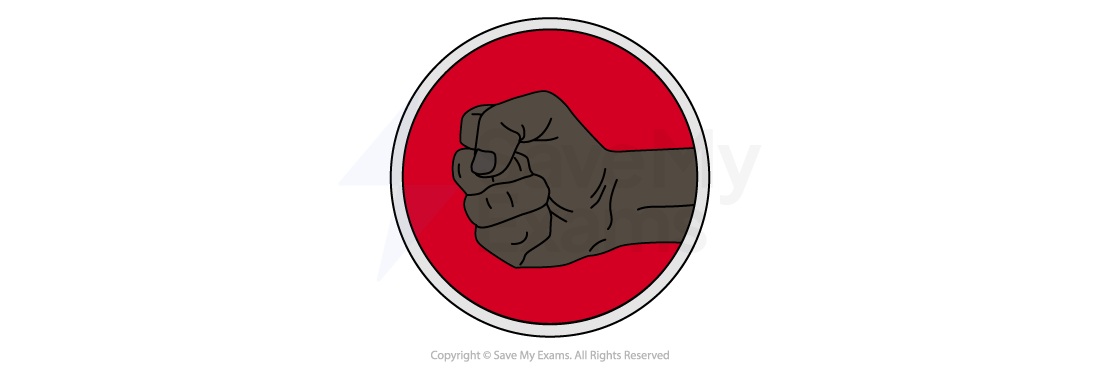

Masculinity and violence

Pigeon English deals directly with the challenges young boys face growing up in a poor and violent area of London, especially if they are Black. The links between violence and masculinity are constant, with every male character touched by it. With consistent violent actions, imitation and verbal threats of violence, the reader is overwhelmed by the frequency of these episodes. However, Kelman forces us, as Harri must, to get used to this world of violence and aggression.

In all of his friendship groups and peers, Harri is presented with violence and aggression as something to boast about:

Early in the story, the X-Fire has an audience in the palm of his hands as he shows off how to “chook” someone

Jordan boasts about the amount of people he’s stabbed

His friendship group with Dean and others draws scars on themselves and compare each other by who is strongest

The Dell Farm Crew is impressive to Harri, even when he doesn’t approve of their behaviour:

In that group, Harri believes X-Fire is the leader because he “is the best at fighting”

When the Dell Farm Crew threaten and steal from Dean, Harri feels sorry for Dean, but “couldn’t help admiring it”

What Harri does not realise is the impact that violence is having on him subconsciously:

The escapism constantly on show in the book shows children trying to use their imaginations and make games of things that are otherwise terrifying:

When Harri notices Julius’ bat has scratches all over it, he envisions the bat as a dog and that “all the scratches are from where it got in a fight with another dog”

Harri and Dean’s investigation makes a game out of murder, and means they can pretend it is just like TV

The scars the boys draw on themselves as a game is another way of making brutal injuries into something fun

The painting Harri does in school shows how Harri’s subconscious is much more uncomfortable with the violence than he realises:

When it comes to doing the red, for the dead boy’s blood, Harri says it’s “very vexing” that he cannot get it right

That his eyes go “all blurry” and Poppy looks at him with concern shows that Harri has an unhealthy fixation on the blood and it is coming out in ways he cannot articulate

It is interesting that art is used by Kelman to show Harri’s true fear, as art is often said to be therapeutic to deal with emotions under the surface

The violence and anger perpetuated by the gang is then mirrored by those outside of it because it is part of their society:

When Harri is upset about the tree getting cut down, he gets angry at the smaller children who don’t care:

His anger rose up quickly and “the blood just came from nowhere"

Harri pushes a smaller boy over and “even wanted him to cry”

Violence was his instinct to feel better

Harri and Dean force smaller children off a mattress found on the green, and then look to charge them to use it:

This happens directly after Dean has £1 taken off him by the Dell Farm Crew

We see Dean’s language change when he’s with just Harri, and then a second later when the younger boys are around:

Dean calls the Dell Farm Crew “numpties” when they’re out of earshot, but then is happy to swear (“piss off”) at the younger kids

The need for power and status is clear in the male communities

Harri sees that power over others and violence gives people control:

X-Fire commands the attention of the younger boys when he is showing how to stab and mimicking the killing of the dead boy

When the Dell Farm Crew tell Harri to set off the fire alarm as an initiation, he is tempted to join by the idea that Vilis “couldn’t abuse me anymore” if he was in the Dell Farm Crew

Harri is told that X-Fire can protect him

Harri respects that the Dell Farm Crew “own the steps” outside the cafeteria

We see the control the gang has over Jordan, who doesn’t get paid for the phones he steals for them

We also see how violence touches women, but it is always carried out or inspired by men:

It is mentioned on three different occasions that Killa is burning Miquita

Only later on do Lydia and Harri finally admit that it is violent and confront Miquita about it

Harri thinks it was Julius’s bat that broke Auntie Sonia’s foot:

Moments later, Sonia explains that Julius would “never let me leave”

We see two examples of Miquita being violent to others, and both times are to protect Killa:

First, she burns Lydia when straightening her hair, mirroring the exact punishment Killa gives her

Then she fights Chanelle and even tries to throw her out the window

Both incidents happen because Miquita thinks they may expose Killa’s involvement in the murder

The Dell Farm Crew exist in a world of constant, meaningless violence:

Killa murders the dead boy over an argument playing basketball

The Crew won a war for stairs, getting into a fight just for a place to sit

When they take money from Dean, they know the boys have no real money, but it is just something they do, even for one pound

Their attack on Mr Frimpong is not targeted:

They just attack the next man who comes around the corner, and do not seem to care that is not a rich man, nor do they scout to see if they can steal anything valuable

The vandalising of the church is done for no end, merely entertainment:

The idea that the man must appear strong, the sense of fragile masculinity, and the casual sexism of that can be seen by Harri’s ideas now that his father isn’t there:

Harri calls himself the man of the house, and says that that means it is his job to protect his family:

This view of the man being stronger and the protector is a common belief that is shared across both of Harri’s homes

This is echoed by Julius, who tells Harri that “the only friends a man needs, his bat and a drink”:

He goes on to say that Harri will learn about that one day, but to “stay good for as long as you can”

This shows that Julius, a violent man, does feel remorse for what he has done, but believes it is the only way to survive

It also shows that he was made this way, not born, more sign that the nature of masculinity around this area turns men violent

The pigeon often talks about the violence in the world, speaking of Harri’s world and our own:

He talks of the temptations of violence, and how it always “came too easy to you”

We also see the mirroring of Harri and the pigeon when it is attacked by a group of magpies:

Clearly, the magpies represent the Dell Farm Crew, and Harri the pigeon

It says, “they think I’m one of them”, which is similar to how the Dell Farm Crew see Harri

Equally, the pigeon complains about them fighting “over scraps”, which speaks to how the Dell Farm Crew hurt and intimidate for unimportant things

What is Kelman’s intention?

The violence and the gang culture of the story are direct links to the murder of Damilola Taylor, killed by two members of the Young Peckham Boys Gang:

London was, and still is, gripped by issues of youth violence, and Kelman uses this story to highlight the impact of this on young people

Kelman highlights how drawn these young men are to violence within a societal structure that makes nothing else easy for them, nor gives them much alternative

The cyclical nature of violence is a key theme Kelman wants us to ponder, showing us how the problem moves from group to group, victim to victim:

Harri is unable to escape it, and ultimately shows signs of using it when it advantages him

Kelman also shows that boys lacking healthy role models learn that violence proves their masculinity:

The damage of this attitude is proved in the disastrous, and deadly, consequences in the novel

Death

Pigeon English examines the effect of death becoming a common part of a community and a child’s experience. The novel begins and ends with death, and death impacts all aspects of the estate and its residents. It hangs over the community, and shapes the actions and thoughts of all of the novel’s characters: Harri becomes fixated by it; Lydia becomes caught up in it; we see how the guilt affects Killa; and how it becomes a weapon for someone like X-Fire.

Knowledge and understanding

Pigeon English shows us what death can take from us; not only does it take lives and futures, but it takes away innocence, safety and security:

We see two lives ended, both victims shown as vibrant, talented boys

Dean and Harri’s investigation shows how death and murder is normalised for them:

What should be shocking becomes a game

The Dell Farm Crew all accept killing and death as part of their lives:

Knowing how to stab someone is expected, and boasting about killing is commonplace

The other boys, Harri’s younger peers, obsess over scars

Harri becomes increasingly anxious about death across the novel:

Early on, he hopes to bring the dead boy back

He then imagines his own coffin at the funeral

Later, he fears for Agnes, and offers to trade his life for hers

Killa is pained throughout, scared both about repercussions for his actions, and the guilt for the murder

Harri is fascinated by death, but approaches it with an immature frame of mind, and not finality:

While Dean is solely trying to solve the case, for Harri there is more belief about the spirit of the dead boy, going as far as trying to see it

Harri tells us about a “miracle” where a young man was brought back to life in Ghana

At the start, when looking at the dead boy’s blood, Harri is comforted by making “the blood move and go back in the shape of a boy”, in a way that may bring the boy back to life

When he dies, Harri believes he is going on to heaven, again ignoring any finality

When Harri’s Mum watches the news, Harri says that somebody dies every day, and that it is “nearly always a child”:

This is the norm for Harri and his community

Harri is unconcerned, only believing his Mum enjoys watching sad news

That the novel begins and ends with death is a comment on the cycle of death in the community:

Harri becomes the next victim, another one to the tally that would bring other communities to a halt

Just as Miquita suggests that the first boy had it coming, others like Jordan or Killa would say that Harri did

We hear on the news that the police are imploring witnesses to come forward, but have been met with silence

The community has closed ranks, between fear of each other and mistrust of the police

Speaking up may see them ending up as the next victim:

This mirrors what the police found when investigating Damilola Taylor’s murder

Lydia and Harri could both go to the police at different times, but do not out of fear

Chanelle is attacked when it is believed she might speak out, while the fear for Harri’s life is increased once the Dell Farm Crew catch him with the wallet

Throughout the story, adults tell Harri to stay clear of troublesome peers, knowing what can happen

What is Kelman’s intention?

Kelman shows how Harri is scarred by death being a part of his life, and that trauma shapes minds

He also shows us that we are discarding lives by perpetuating the problems of these areas

Equally, he shows us how people have to adapt, and become hardened, like Miquita blaming the dead boy:

This could be a comment on how we are forcing people to accept this as their fate, and be irrevocably changed

Sources

Kelman, S. (2011). Pigeon English. Bloomsbury

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?