Benzene (OCR A Level Chemistry A): Revision Note

Exam code: H432

Comparing Models of Benzene

The structure of benzene (C6H6) was a long-standing puzzle in chemistry

Two models are used to describe its structure:

The early Kekulé model

The modern delocalised model

The Kekulé model

This model proposed a hexagonal ring of six carbon atoms with alternating single and double C-C bonds

It suggests that the π-electrons in benzene are localised within these three double bonds

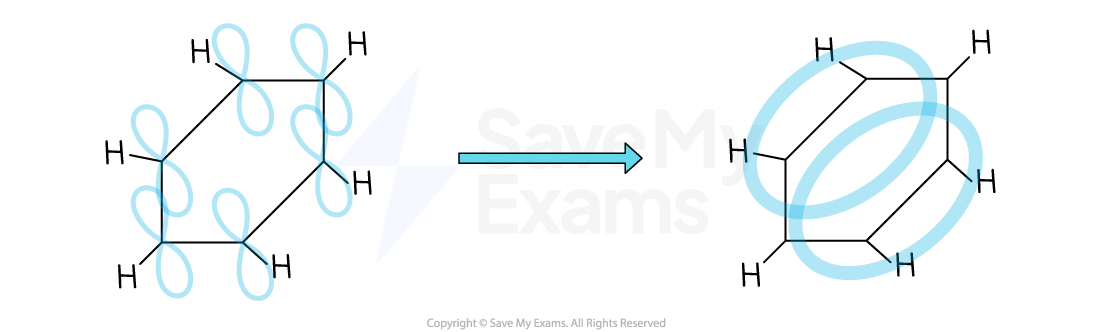

The delocalised model

This is the accepted modern model

It proposes that the p-orbitals of all six carbon atoms overlap sideways, both above and below the plane of the ring

This overlap forms a continuous ring of electron density, creating a delocalised π-system where the six π-electrons are spread over the entire ring

Evidence for the delocalised model

There are three key pieces of experimental evidence that support the delocalised model over the Kekulé model

1. Bond lengths

X-ray diffraction analysis shows that all six carbon-carbon bonds in benzene are identical in length at 0.140 nm

This contradicts the Kekulé model

The Kekulé model would have alternating short C=C double bonds (0.134 nm) and long C–C single bonds (0.154 nm)

The measured bond length is intermediate between a single and double bond, supporting the delocalised model

2. Molecular shape & bond angles:

X-ray diffraction also shows that benzene is a perfectly planar (flat) regular hexagon

All C–C–C bond angles are identical at 120°

This contradicts the distorted ring of alternating 120° and 109.5° angles that a strict Kekulé model would imply

The perfect hexagonal shape is only possible if all six C-C bonds are identical

3. Enthalpy of hydrogenation:

The hydrogenation of cyclohexene (one C=C bond) has an enthalpy change of -120 kJ mol-1

C6H10 + H2 → C6H12 ΔHΘ = -120 kJ mol-1

The Kekulé structure (with three C=C bonds) would therefore be expected to have an enthalpy of hydrogenation of 3 × (-120) = -360 kJ mol-1

C6H6 + 3H2 → C6H12 ΔHΘ = 3 x -120 kJ mol-1 = -360 kJ mol-1

However, the experimental value for benzene is only -208 kJ mol-1

This means benzene is significantly more stable (less exothermic) than the Kekulé structure suggests, due to the energy of the delocalised π-system.

Summary of Kekulé vs. delocalised models

Feature | Kekulé model | Delocalised model |

|---|---|---|

π-electrons | Localised in 3 alternating C=C bonds | Delocalised in a π-system across all 6 carbons |

Bond lengths | Alternating short (0.134 nm) and long (0.154 nm) | All identical and intermediate (0.140 nm) |

Shape & angles | Distorted hexagon with non-uniform angles | Regular planar hexagon with uniform 120° angles |

Stability | Less stable (predicted ΔHhyd = -360 kJ mol-1) | More stable (experimental ΔHhyd = -208 kJ mol-1) |

Benzene Resistance to Halogenation

This is a key piece of chemical evidence for the delocalised model

Halogenation in alkenes

Alkenes (like cyclohexene) have a localised region of high electron density in their C=C double bond

This is strong enough to polarise an approaching Br2 molecule

This results one δ+ bromine atom and one δ- bromine atom

So, a rapid electrophilic addition reaction occurs at room temperature

Halogenation in benzene

In benzene, the electron density of the six π-electrons is delocalised and spread out over the entire ring

This means the electron density at any one point is lower than in an alkene's C=C bond

So, it is not strong enough to polarise the Br2 molecule

Therefore, benzene does not react with bromine under normal conditions

Benzene resists addition reactions as this would disrupt the very stable delocalised ring

Instead, it undergoes substitution reactions

This requires a halogen carrier catalyst, such as AlBr3

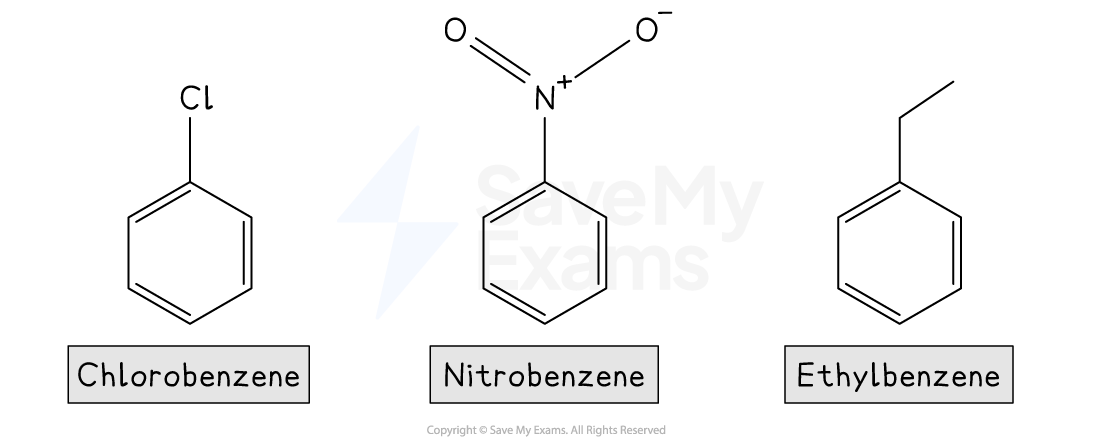

Nomenclature of Aromatic Compounds

In chemistry, aromatic compounds are those that contain one or more benzene rings

The IUPAC rules for naming simple substituted benzenes involve using the substituent name as a prefix, followed by "-benzene"

For example:

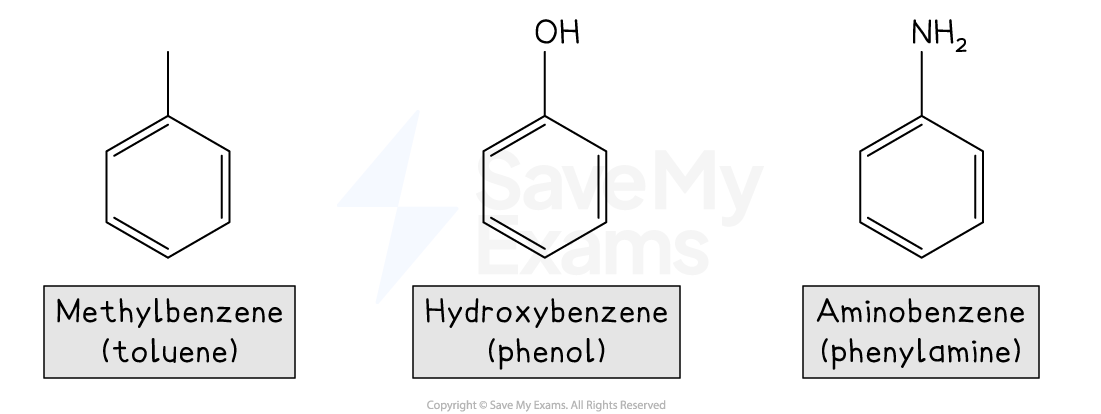

Some common aromatic compounds have accepted trivial names that you should know

For example:

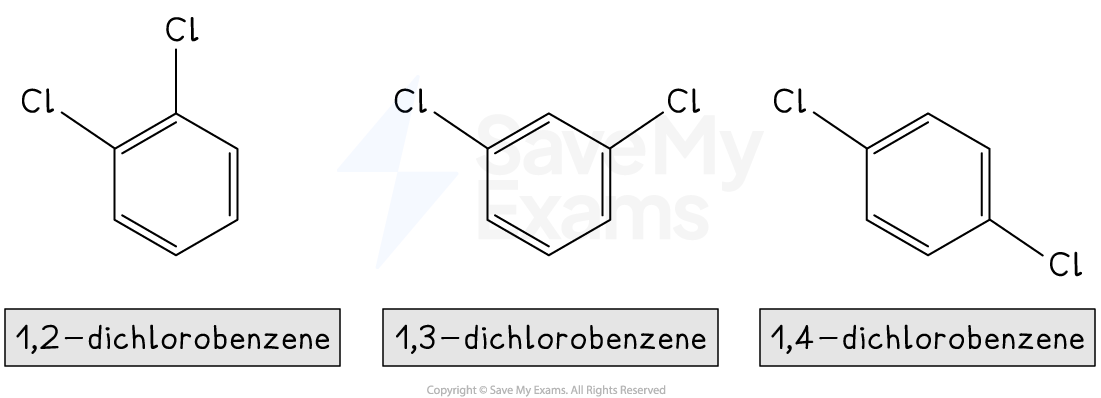

For multiple substituents, numbers are used to indicate their positions on the ring

The goal is to use the lowest possible numbers

For example:

Unlock more, it's free!

Was this revision note helpful?